|

|

William Saroyan,

in his introduction of Leon Surmelian's "I Ask You Ladies and

Gentlemen" (1945, Dutton), called the book "gentle,

civilized" and "a story without hate." And one of the

remarkable features of this book is that its author does not automatically

make all Turks out to be monsters. It is this disarming quality that makes the

"extermination" chapter all the more alarming. Since Surmelian

sounds so credible, the evil acts he presents come across as believable.

And perhaps they happened just the way in which he

depicted them, during the "death march." No one denies there were

times the Armenians were abused, even by the gendarmes who were assigned to

protect them.

Yet Surmelian provides giveaway signs of his own Dashnak

mentality, even when he was a little boy. As objective observers are keenly

aware, trust is not a favor to be granted to the

"end-justifies-the-means" Dashnak personality.

As K. S. Papazian astutely concluded in (p. 67 of) his

1934 book, "Patirotism Perverted," the Dashnaks'

"hands are raised against everybody, its plots and crimes have rocked the

conscience of all decent Armenians, and have disgraced our people before the

civilized world."

So was Surmelian being honest in his reportage, or was

his "unhateful" style a sneaky bone that he threw, in the knowledge

such would have presented a more believable format for his Dashnak ideology

and his service for the "Armenian Cause"? As with the rest of the

"genocide" madness, you weren't there and neither was I.

The fact is, throughout his narrative, Surmelian wastes

little opportunity in painting the Turks in the same brush as typical Armenian

propaganda. The Turks are stupid, sinister, and basically evil, despite token

descriptions of humanity (which are quite laudable, given their absence in the

"regular" channels). On the surface, there is then an "unhateful"

nature with the book. But as with the "genocide," if one wishes to

get to the truth, one must scratch beneath the surface. It does not take much

scratching to conclude that, despite what Saroyan tells us, "I Ask You

Ladies and Gentlemen" offers quite a bit of hatred... as we'll soon

see.

The clarity with which Surmelian remembers the most

minute details from thirty years ago, as a nine-year-old, already is the

greatest cause for suspicion. The way he rounds out the story with the

injections of "Armenian genocide-speak" (such as all the Armenian

men being subjected to annihilation... as if today's worldwide Armenian

population could have reached 7 million from what was 3 million, had all the

men been wiped out) makes it appear that he used this opportunity to lay on

the typically deceptive Armenian propaganda.

Regardless: the book offered some interesting

observations aside from the "cause" that are worth taking a look at.

|

|

|

| |

Leon Surmelian and his family were in Trabzon/Trebizond

when the war started. The two Armenian newspapers were the "prudent" Byzantion

and the "hot-headed" Azatamart. His pharmacist father comes across as one

of the many good Armenians who was trapped between loyalty to the state and the pressures

brought upon by the greedy, fanatical revolutionary leaders. ("Father

was strongly for Armeno-Turkish friendship, and the only Armenian in Trebizond critical of

Russia... he heaped again his scorn for the Armenian Revolutionary Federation. 'It's

destroying our nation! It has ruined our schools, disunited our people. What do your

people know about international politics? Wasn't it all this revolutionary foolishness

that started the Massacre?'" Three cheers for Surmelian the senior!)

The fact that Leon Surmelian had a

"humane" Armenian for a father (an intelligent father whom Surmelian deeply

respected for being "always right"), and a mother who shunned political

conversations (and thus, theoretically, would not have served as an anti-Turkish

influence) makes it all the more profound that Surmelian harbored such traitorous feelings

for his Ottoman nation, as he reveals time and again... even as an impressionable

nine-year-old. (At such a young age, often it is the parents who do the impressing.) Thus,

ironically, the one truth that is revealed from "I Ask You Ladies and

Gentlemen" is that young Surmelian represented the way most Armenians must have

felt. The "average Joes" of the Armenian community — not all, but

all too many — were basically anti-Turkish and ready to collude with the enemy

during wartime.

It appears Surmelian's Uncle Leon was a member of

the Dashnak Armenian Revolutionary Federation, at odds with a cousin named George. ("Brother George, as we children called him—was hardly on speaking terms

with Uncle Leon, because of past party quarrels. He had been a member of a rival

revolutionary faction, the Hunchak, or Bell, and still had a revolver. But he had resigned

from the party, disillusioned and bitter, and withdrawn from all political activity.")

[Pg. 17]: "An old Turkish beggar was calling on us. Turkish

beggars did not fare very well in our exclusively Christian street; our old clothes and

leftover food usually went to Christian beggars but we were extremely generous with this

man... We were quite certain that God, seeing our good deed, would summon back the angel

of death and permit Uncle Harutiun to live."

This passage indicates the Armenians in this

neighborhood were isolated from the Muslims; this was not always the case from other

accounts I've read, where there was a community feeling between the two groups. (More on

this later.) In this example (along with other clues that will emerge), we can see there

is a "looking down on" the Turks, even at the level of the beggars. (I'd presume

most would feel those who have hit bottom are of the same class, and don't deserve further

prejudice.) Much the same way as Ohanus Appressian revealed in "Men Are Like That":

"I can see now that we Armenians frankly despised the (Turkic) Tartars, and while

holding a disproportionate share of the wealth of the country, regarded and treated them

as inferiors." This is a recurring theme in much of

Armenian literature, and surely too many Armenian youths from Internet forums have nothing

but contempt for what they regard as "racially inferior" and subhuman Turks.

It's interesting the family decided to become

charitable with the beggar in the hopes of being rewarded for their "good deed."

|

|

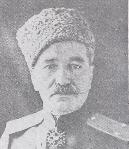

Antranig

Ozanian |

Uncle Leon was again reassuring [about the real

attitude of the Ittihad]. "It’s common knowledge in Constantinople that the

minister of the interior, Talat Pasha, dines and plays backgammon with our party

leaders,” he said. “And the Ittihad does what he says. Jemal Pasha, the new

minister of the navy, is also friendly.” “How about Enver?” That was the most magic

name of all for the Turks. “Enver had nothing but praise for our soldiers during the

Balkan War. It wasn’t easy for our boys to fight against the Christian Bulgarians —

with Antranik serving in their army. (...) But Uncle Leon... also had words of caution for

them from the party leaders. “We can dine and play backgammon with them, but we must

never cease to organize. They can fool us again...”

A quick look at Jemal Pasha, according to the

notorious Turk-hater, Johannes Lepsius, from his

book, Deutschland und Armenian: "Jemal Pasha... prevented serious rioting in

his district and took some steps to feed those who had been deported and provide necessary

services..." At another point in the book, an April 1, 1915 telegram from German

Consul Rossler states: "Jemal Pasha gave the order... any Mohammadan who attacks an

Armenian will be court-martialed." The fact is, Jemal Pasha always stood up for the

Armenians, and his reward was to be murdered at the hands of Armenian terrorists.

Surmelian's paragraph above continues with a deeper

condemnation of how evil the Turks really are, but I ask you this, ladies and gentlemen:

how feasible is it for leaders to show a genuine friendliness toward Armenians to later go

and conduct an extermination policy against them? In his book, I'm not sure whether

Surmelian provided a murder motive (I didn't have the luxury of examining at length, aside

from a quick read-through, and a hurried xeroxing of some pages), but the typical one is

that the Ottoman Empire intended to "Turkify" the nation, that is, pan-Turanism.

If the motive was based on such racism, can you imagine the pretense of dining with the

object of racial hatred, and playing board games with them? Would Hitler have asked a Jew

to share a few beers?

On the other hand, a good reason why the Armenians

gained their reputation for disloyalty is that they thought little of demonstrating

outward friendship while colluding with the enemies of their country; if

"fooling" was taking place, it was on the part of the Armenians.

While it was nice of Surmelian to reveal the Turkish

leaders had human dimensions — that was far more to expect than your general Armenian

"genocide" writer — the author's real intention appears to be the

demonstration of how really inhuman these Turks were. The style of "civility"

troublingly comes across as a pretense, akin to the Nazis' playing sweet music for

concentration camp arrivals. (Surmelian will go on to give a really atrocious example of

this, with two Turkish boys who had befriended him, coming up.)

[p. 62] We all knew the Turkish march:

Yashasun hurriet, edalet, mussavat,

Yashasun millet!

Long live liberty, fraternity, equality,

Long live the people!

Brass-band words borrowed by the Young Turks from the slogan of the

French Revolution. That such words should exist in Turkish, we thought. . . . Yet the

music was good, and we sang it lustily, with imitations of various band instruments.

Yes, here the Armenians were granted an autonomy by the Ottomans when the

Armenians' previous rulers, the Byzantines, did not... and even when the Armenians'

rulers-to-be, the Russians, would not... allowing for the Armenians to maintain their

national identity since the 11th century (starting with the Seljuks), and Surmelian

provides this awful dig for his unwary English-speaking reader, already immersed in

"Terrible Turk" propaganda. The funny thing is, the more "liberty,

fraternity, equality" the Armenians were granted, the greater would Surmelian's

beloved Dashnaks (and other fanatical revolutionists) feel free to draw a deeper wedge

between the two peoples. Once again, Surmelian doesn't miss the opportunity to slip in an

untruthful assertion, in his "gentle, civilized" fashion.

How Valid was "Liberty, Fraternity,

Equality" in 1915 France?

Let's examine the concept ninety

years later:

"Many of France's estimated 5 million Muslims

feel the country has promised more than it has delivered. Not surprisingly, despair

and anger run deep.

Liberté, égalité, fraternité are ideals

that France has nurtured over the centuries. But they were in little evidence last

week around Paris."

From "Why Paris is

Burning," TIME Magazine, Nov. 14, 2005, p. 38

In other words, it's easier to have

"liberty, fraternity, equality," in nations that are homegeneous. 1915

France had much less of a melting pot than in 2005. How much "liberty,

fraternity, equality" do you think a North African immigrant enjoyed in 1915

France?

And let's not forget an important

difference. "The Other" (Moslems) in 2005 France want to be accepted as

French. They want integration. As the article explains, while on paper they may have

equal rights, "many suffer from persistent

discrimination." A viewpoint

on the same page, "How Much More French Can I Be?", tells us the

previous generation "did all they could not

just to fit in but to become invisible. Calling attention to themselves meant

trouble — endless ID

and visa checks from police, racist remarks and insults — so they avoided all that."

By contrast, "The Other"

Armenians in the Ottoman Empire, in the centuries when they desired to fit in,

prospered to the point of having, on average, more comfortable lives than the

average Turk. Those who lived east, where the Ottomans had less control, faced

danger from lawless bands. What we're never told is that everyone faced the same

danger from these lawless bands.

The troubles began in the 19th

century, when greedier Armenians no longer wanted integration but separation.

|

While last fall I was visiting in California I

spent a day with Leon Surmelian, the author of "I Ask You Ladies and

Gentlemen." In the course of a conversation, as we were discussing the Fedayi

commanders, Leon suddenly said to me: "Dro was the greatest commander of them

all; he was never defeated in battle."

Now Leon is not a military man nor is he a

historian...

James G. Mandalian, DRO, The Armenian

Review, June 1957

Indeed, Surmelian is no

historian. He is yet another Armenian believer who has allowed the false Armenian

version of events to wash all over him, if he's going to make a ridiculous statement

like Dro's never having been defeated. (Dro was Armenia's war minister in the 1920 war with the Turks

that led to Armenia's crushing defeat [under an administration Surmelian himself

served under]; the cowardly, terroristic butcher was best in battle when facing

defenseless villagers to exterminate, not real soldiers. Fables of his valor and

military genius come strictly from Armenian historians.)

In his book, Surmelian's heart

belongs only to Antranik; it looks like his hero-worship of Armenian mass-murdering

heroes took another turn, in later years.

|

[p. 64] Avedis had tried to organize the first trade

union in Trebizond, and staged a demonstration on May Day by unfurling a large red

flag on the Gray Hill, and then with a band of his comrades, mere schoolboys,

marching into the city singing La Marseillaise and an Armenian socialistic song. The

Turks thought the Armenians of the city had risen in revolt, to establish a kingdom

of their own—their old bugaboo—and a mob of Laz cutthroats, dervishes,

theological students, and other such patriots, armed to their teeth, gathered in the

Maydan, the central plaza, to “suppress” this new rebellion of the infidels.

Fortunately the town commandant happened to be a more enlightened man and knew

something about May Day celebrations in Europe. When the alarmed leaders of our

community appealed to him for protection, he sent troops to disperse the murderous

mob, and a massacre was narrowly averted.

In the entire book, Surmelian

gives overt examples of the Armenians' treacherous disloyalty (especially deriving

from himself, as the best example), and the possibility of Armenian revolt is termed

as an insignificant "bugaboo"? The thousands of Turks the vicious

Armenians subjected to outright murder, especially in the past forty-odd

"terrorist" years, was a very serious matter.

An example of losses (albeit

exaggerated) comes from the diary

of Aghasi, who began the 1895 Zeitun rebellion: "From the beginning until the

end of the insurrection, the Turks lost 20,000 men, 13,000 of whom were soldiers,

and the rest were bashi-bozuks [irregulars]. We had lost only 125 men, 60 of whom

had died in battle, and 65 of whom were dastardly killed during the

cease-fire." (p. 306] )

As W.W.I approached,

the local residents had good reason to fear Armenian treachery... for quite unlike

the innocent martyr nation the world came to know them as, when Turks were at the

mercy of Armenians, rarely was mercy shown.

Note how this episode

is presented: the Muslims are such an inferior sub-species, it is in their nature to

massacre, in a heartbeat. If the Ottoman Muslims were so dangerous and murderous,

wouldn't the time to have approached the "enlightened" commandant have

been before the May Day celebration had taken place?

"If the Turks had attacked us, we would

have defended ourselves," Uncle Leon said, while Mother got up and left the

room. These political arguments in our home made her acutely unhappy.

"Defended with what?" Father shouted.

"Our party had eight hundred members in

our region."

"All right, you had eight hundred heroes

against how many Turks? — eight hundred thousand, with millions more behind them.

Did you expect the British fleet to force the Dardanelles to come to your help—and

climb maybe to the top of Mount Ararat? Or did you think the Russian Emperor would

declare war on the Sultan because Avedis was waving a red flag and singing

socialism?"

I did not know what socialism meant, I did not

understand half of what they said. Though it seemed to me that Father was right—he

was too smart to be wrong—and though George and Vertanes agreed with everything he

said, and disagreed with everything Uncle Leon said, I was nevertheless heart and

soul for Uncle Leon. In fact I resented my cousins...

The fact that the

revolutionists might have been numerically inferior never stopped them from creating

riots and massacres in years past. After centuries of harmony, the sequence for the

troubles that occurred nearly always followed the same pattern: The Armenians would

ACT, and the Turks would REACT. If the Armenians had not stirred trouble... if they

had remained loyal, as they were up to the 19th century... none would have had to

fear a "massacre." (Just as Surmelian's dad said. He was too smart to be

wrong!)

Although father served as the

voice of reason and was "right," Surmelian's heart and soul still belonged

with his Dashnak uncle. A good revelation as to how the ordinary Ottoman-Armenian

must have felt, after years of prior agitation by the missionaries and the

imperialist powers.

[p. 65] I wanted to ask Father, "Then why

do you call Uncle Leon, and not Brother George or Brother Vertanes, to protect you

with his revolver when you go out at night?"

Father was in terror of the Turkish toughs who

attacked Christian pedestrians in the streets, robbed them, beat them, and sometimes

knifed them to death. The main street, from his pharmacy to our home, was fairly

safe, but the dark crooked narrow side streets were not. We had to carry a lantern

when we ventured into these perilous alleys on visiting our relatives. When it was

Father’s turn to keep his pharmacy open until past midnight, or when he went out

after supper, Uncle Leon had to accompany him as bodyguard.

It's amazing Father was

evidently never a victim of a mugging, after years of such operation. As if a second

man (the "bodyguard") would be of much use if a small gang were of the

mind to cause mischief. Yes, lawless criminals is a problem peculiar to every

country, and the gangs in this part of the world were surely not exclusively

Turkish. The Turkish ones most certainly did not ask their victims if they were

Christian before attacking them. The truth is, everyone suffered from toughs of all

stripes, particularly in regions of the empire where Ottoman control was weak. (This

type of account would be rare in an area where control was strong, as in Istanbul.)

Yet note again how the author gives the impression of anti-Christian persecution. .

[p. 66] We continued our vacation, and then

suddenly there was a war in Europe. The Great Christian Powers were fighting among

themselves. And Turkey, backed by Germany, saw her chance of settling old scores

with Russia and her allies—our friends.

Was that the reason? The

bankrupt, war-weary Ottoman Empire suddenly decided this would be a good opportunity

to take on the combined might of Russia, England and France? Or did the reason have

more to do with how these nations were trying to take the empire apart, reducing the

empire to little more than a European colony.... so that the Ottomans knew if the

Entente Powers were to win against Germany, nothing would stand in the way of the

empire's dissolution? Even with this backdrop, the Ottomans dragged their feet, and

would have entered as easily on the side of the Allies as with Germany, if not for

circumstances that real historians know all too well.

These "Great Christian

Powers" were some "friends"

of the Armenians, by the way. Even if they behaved like real friends, if your nation

goes to war, then these friends would need to stop being regarded as friends. Yet,

the Ottoman-Armenians decided to betray their nation, by choice or coercion, and

became "belligerents de facto."

As if to signal the approach of our doom there

was a total eclipse of the sun at this time. Old women in the village shook their

heads and said gravely: “It’s an ill omen. May God protect us."

An allusion to the oncoming

"genocide." However, if there were such an omen, it affected all Ottoman

peoples. The Muslims who suffered in far greater numbers did not count, and still

don't count... including the over half-million who died as a direct result of savage

Armenian treatment, along with some Russian help.

We found the city a veritable war camp in

September, with ships in the harbor unloading troops and supplies, and Turkish

soldiers, trained by German officers, marching off to war goose-stepping.

Let's keep in mind the book's

release was in 1945, when terms like "goose-stepping" had a particularly

chilling effect. The description brings us a step closer to "genocide."

Men and materials were being rushed to Erzurum,

the great fortress breasting the Russian Caucasus.

There was a general

mobilization. Vertanes, wearing the uniform of a Turkish lieutenant, came to bid us

good-bye. He, too, was going to Erzurum. He let me play with his sword. I practiced

drawing the long heavy blade out of its scabbard. If he was worried, he tried not to

show it. He knew he looked well in his uniform. The ends of his black mustache were

waxed and twisted up like Enver Pasha’s. He was in the medical corps. He asked

Nevart to play the piano for him once more, and when she finished her number, he

clapped his hands and cried, “Bis! Bis! Repetez!” with his customary enthusiasm.

He acted as if he had done nothing all his life but attend concerts.

Uncle Leon, being a widow’s sole support, was

allowed to pay an exemption tax of forty gold pounds—half of which he had to

borrow from Father.

“Before long they will take me too,” Father

said gloomily. “It’s going to be from seven to seventy.” The schools opened as

usual, but Trebizond was not the same city any more.

Why would father have thought

the mobilization would grow to be so all-encompassing? In his wisdom, he must have

recognized what a desperate situation this was for his country. Far from the Ottoman

Empire's opportunistically choosing to go to war, as son Surmelian informed us, the

Ottoman Empire would face three of the greatest superpowers of the period. Indeed,

all the fighting the Ottomans were engaged in during W.W.I was of a

"defensive" nature (save for Enver's ill-fated attack leading to

Sarikamish, at the outset).

Given this desperate

life-or-death struggle, where every man was needed to hold off such superior forces

from multiple fronts, the Armenian soldiers were of great need. This would be the

worst time to initiate an "extermination" program, even if the Ottoman

Turks were of the mind to do so. The securing of the borders would have needed to

come first, otherwise there would be no land left to "Turkify" anything,

particularly with the treaties the

Allies had agreed upon secretly, to divvy up Ottoman real estate. This is only

common sense. And Leon Surmelian has indirectly borne witness to this fact, through

his father, who was always right.

|

| Chapter 5: My Turkish

Playmates |

[p. 67] The frog said to the heron, “Please take me up with

you, friend heron. I am tired of living in this slimy water.”

The heron replied, “Very well, friend frog. Hang on with your

mouth to this stick in my beak. Take care not to say anything while we are in the air. Be

sure to keep your mouth shut.”

“I will not say a word,” the frog promised.

So they went up together. The heron flew over fields and

mountains, and the frog was delighted. But soon it forgot its promise, and as it opened

its mouth to speak, it fell to the ground and was killed.

OUR Turkish lesson that day was about the frog that talked too much.

There were many stories with a moral in our Turkish reader. This particular lesson made me

think of what my father often said: we Armenians talked too much; we did not know how to

keep our mouths shut. Thus we proclaimed our love for Russia, England, and France from the

house tops. The Turkish comic paper Karagoz had truthfully said, If you want to know

the situation in the Dardanelles, look at an Armenian’s face.

The Turks were very different from us; one could never tell what

they really thought, what they really knew. They kept their secrets to themselves, and if

they talked, they often meant the opposite of what they said.

(Another look at the Karagöz cartoon.)

The above passage is very telling. It gets to the

heart of the matter as to why the "Armenian Genocide" has become the accepted

wisdom throughout the world. The Armenians are noisy and screech at every opportunity; the

Turks prefer silence.

This difference is the reason why there is no limit

to Armenian "Oral History," and the Turkish counterpart is difficult to find.

It's because the Turks don't like to speak of their sufferings, they are the polar

opposite of a "please feel sorry for me" people. This British archival source

provides understanding, as [Shown

here on this page].

Prof. McCarthy’s “Death and

Exile,” utilizing mainly Western sources, offers a telling footnote from page 97,

referring to the fate of the Balkan Turks, at the hands of murderous Greeks, Serbs,

Bulgarians and Montenegrins... all of whom truly carried out a policy of systematic

extermination, in an effort to frighten the rest of the Turks into leaving their lands

(a policy also carried out by Armenians in the Anatolian east, and to a lesser

"murderous" extent, in 1992 Karabakh):

"One might be pardoned if,

on reading of the various atrocities visited upon the Balkan Turks, it seems as if the

atrocities were invented, or at least much inflated, by those who allegedly suffered.

One answer to this is the type of confirmatory evidence provided by the European

consuls, reporters, and other observers. I believe, though, that the evidence drawn from

Muslim refugees was generally reliable in itself. Those who in 1876-78 had long dealt

with Turks avowed that Turks were very unlikely to overstate their suffering. Quite the

opposite was true - Turks were unlikely to mention their defeats, or to underplay them,

and the massacres of the Balkan Turks were a horrible defeat. British Consul Blunt at

Edirne spoke of the difficulty of getting Turks to speak of their sufferings, because of

the ‘habitual reluctance of the Turks to speak of indignities to which any among them

have been subjected. (It is this very policy, I may add, which induced them to conceal

from public knowledge, rather than denounce the mutilations constantly practiced by the

Montenegrins on their Turkish victims.)’ " (F.O. 195-1137, no. 90, Blunt to

Layard, Adrianople, 6 August 1877.)

[Close]

This is the noble, strong, silent method of

behavior, a trait often admired in our movie heroes... as opposed to the "feel sorry

for me" noisy way of behaving, that we usually look upon with contempt. It is this

attribute Pierre Loti referred to in "Fantome d’Orient" (1928), when he

wrote: "The dignified silence of the Turks against the mounting unjustified

attacks and mean slanders can only be explained by their pity for the blind. …How

beautifully this attitude of theirs answers the undignified calumnies."

However, the sad fact is, no matter how

"noble" it is to suffer silently, the way the world works — as the Armenians

and Greeks know all too well — is that it is the squeaky wheel that gets the grease.

Note how Surmelian attempts to turn this

"strong and silent" quality into something to be derided, as when he writes, the

Turks "often meant the opposite of what they said." I'm reminded of U.S.

Secretary of State Robert Lansing's attempt to turn this plus into a minus, when he

characterized a gesture of warmth and friendliness by Talat Pasha (in "Ambassador

Morgenthau's Story") as "Oriental

insincerity." Sometimes the Turks aren't guided by Western standards, as British

P.O.W. Harold Armstrong provided examples of in "Turkey in Travail" ("When we happened to talk of the war,

they told me glowing accounts of the success of the British troops").... but this

eastern mentality has at its root a desire to be sensitive and kind. Of course, such an

attitude could be easily misunderstood by cultures that appreciate directness; on the

surface, it can appear to be phony. Similarly, the "in your face" American style

can come across as crass... and not only by the easterner's perspective, but by most

Europeans, as well.

If we desire to get at the core of what true

dishonesty means, I believe the better determinant is to listen to the multitudes of

Western observations, as the following from Grattan Geary's' "Through Asiatic

Turkey ":

"When a Mohammedan gives me his word,"

said a gentleman who had a long experience of the country, "whether he be a Turk or a

Kurd, I can always rely on it. I have never been what is called ' done ' by a Mussulman,

although I have had transactions of all kinds with Moslems for years ; but when a native

Christian tells me anything, I have cause instinctively to ask myself where the deception

lies — in what direction I am going to be tricked."

And one by Leslie Davis ("The Slaughterhouse

Province," p. 183):

"l[L]ying and trickery and inordinate love

of money are besetting sins of almost all (the Armenians)."

[p. 68] Just a few days before, we pupils of the

Armenian National School had given three Russian prisoners an ovation. They were Cossack

oflicers and had the faces of tigers. They acknowledged our applause and shouts of

admiration by bowing politely and smiling, while their Turkish guards no doubt gnashed

their teeth, but said nothing.

Can you imagine any nation at war that encounters a

blatant show of support for the enemy, from its own populace? Here are these symbols of a

hostile country, anxious to obliterate the Ottoman Empire, being openly admired from a

sampling of the Ottoman people themselves... how should the Turkish guards have felt? What

a remarkable display of toleration to do no more than "silently suffer."

Even today, "Hanoi Jane" Fonda can never

hear the end of spending a little time with the Viet Cong... an enemy that hardly

threatened the existence of the USA, as Czarist Russia surely did with the "Sick

Man."

This is a superb example of how the local Armenians

openly displayed their betrayal. The reader can get a better idea as to why it was not

just the armed Armenian rebels who needed to be targeted; in this atmosphere... and in the

midst of desperate wartime, no longer could friend be told apart from foe, in the

Ottoman-Armenian community. What nation would not have removed this dangerous, belligerent

community outside the war zone?

As Hovhannes Katchaznouni correctly informed us ([One of the main aspects of

Armenian] "national psychology... [is] to seek external causes for [Armenian ]

misfortune."..."), Armenians can never accept responsibility. Here they

openly do the crime, and when they get their just desserts (by being resettled).... they

must blame anyone but themselves.

[p. 69] The school bell rang the fire alarm. We ran down the

stairway into the playground, while the mysterious explosions became one continuous

thunder.

"The Russian warships are bombarding the city!” our director

cried out excitedly. “To the church! Everybody go to the church !"

And to the church we ran, joyously. Here we felt perfectly safe, for

its cross was clearly visible from the sea, and we imagined the Russians were Christian

warriors coming to save us from the Turkish yoke. Perhaps the Russians were already

landing troops! We thought that under Russian rule Trebizond would become a modern port, a

real European city with straight streets and electricity. There was no more magic word in

our vocabulary than "electricity." It summed up all the glamor of Paris, London,

New York.

I was in heaven, listening to the thunder of the Russian guns. The

bombardment lasted about an hour, and was followed by a deathly hush, as if a volcano had

erupted like Vesuvius and buried the town under the rumbling torrents of its lava,

although the Christians were somehow miraculously alive, while all the Turks were dead.

Presently a mob of hysterical women were clamoring for us at the

gate. Aunt Azniv had come to take my brother Onnik and me home.

"Were you afraid?" she asked, pressing us to her.

"Not a bit," I assured her. I was disgusted. I saw a

platoon of Turkish soldiers marching down the street. "I thought the Russians had

landed troops," I said. "Shsh! Be careful! Remember what Father said. The walls

have ears," Aunt Azniv cautioned me, carrying a finger to her lips.

What! Even dear old Aunt Azniv encouraged her

nephew's traitorousness?

As if Russian rule would have provided that

glamorous and "electric" modern lifestyle. (Here's a look at how the Armenians

really fared under the Russians.) Ironically, one

reason why the Ottomans lagged behind the modern world was because the limited budget,

already hindered by the extortion of European Capitulations, had to go to the military...

to keep the Russian bear, and other enemies, at bay. And when the Russian bear kept

killing and exiling Muslims from conquered lands, it was the resource-challenged Ottoman

Empire that was the last stop... these refugees needed to be taken care of. (Refugees who

were aware of the hand treacherous Armenians played at ruining their lives, complicating

relations between the two peoples further.)

|

According to Realities Behind the Relocation, 3,400

Armenians were sent away from Surmelian's area of residence, Trebizond. (p. 131);

Vahakn Dadrian states in his chapter of "America and the Armenian Genocide of

1915" that 8-10,000 lived in the city by the same name, and 55,000-60,000 in

the province (p. 69), the "wholesale liquidation... all but completed" by

mid-to-late August 1915 (p. 88), a good chunk of which ("nor was it

minimal," p. 82) via "drowning

operations."

But we know Dadrian was blowing his usual hot

air from the writings of missionary Ernest C. Partridge, who wrote: "the

Armenians who had lived in this territory and all the way up to the Black Sea (Trebizond), who had survived began to trek back," in

"Mary Louise Graffam," Armenian

Affairs, (Winter 1949-1950). If there

were a true policy of "wholesale liquidation," none could have survived.

|

[p. 70-72] On our way home German army trucks loaded

with Turkish soldiers roared down the main street. The war had brought the first

automobiles to Trebizond, and the Turks believed they were driven by shaitans,

devils, but I knew better. Automobiles were like electricity, products of modern

civilization, of European science.

As we passed by the French school, now

converted to a Turkish military hospital, we saw a group of German army nurses,

young women with pink cheeks and determined chins. They had red crosses on their

white caps and arm bands. This strange Alliance of the Christian cross with the

Turkish crescent disturbed and puzzled me. "Have the Germans become

Mohammedans?" I asked Aunt Azniv.

"No, my dear, I don’t think so. But they

might as well be," she added indignantly.

Quite the contrary, the Germans

often allowed their "Christianity" to supersede their alliance with the Ottomans. One reason why

race-and-religiously prejudiced Germans (like the aforementioned consul, Rossler),

similarly hoodwinked by missionaries and Armenians, provided testimony for the

Armenians' genocide. (An example of this attitude: The Germans treated the Turks

with high contempt, and more than one told me how glad he was to meet another white

man in this “native” country. "Turkey in Travail")

Note how the Turks are painted

as village idiots, and even a nine-year-old Armenian boy betters them, by knowing

what's up with those cars.

The next day we went to school as usual. Many

boys exhibited pieces of Russian shrapnel, and asked big prices for them. I got one

by trading for it a Nestlé chocolate premium, a pocket mirror with the picture of a

pretty girl on the back of it, and two rare stamps. That lovely piece of jagged

steel was now my prized possession. It symbolized the might of Christian Russia.

We were so restless and distracted in the

classroom that even Mr. Ohanian had to rap for order and attention. Well, sooner or

later the Russians would be in Trebizond. The Turks weren’t going to stop them.

Why, one of those Cossacks could cut down fifty Turks!

Two months later the Russian fleet bombarded Trebizond again, and this time it

seemed they would really land troops and occupy the city. The new bombardment lasted

five hours. Buildings were crashing down all around us. it was a terrifying, yet

glorious experience. But the Russian warships steamed away at nightfall, and from

the balcony of a neighbor’s house, in the shell-proof basement of which we had

taken shelter; we watched them disappear.

The next day both Turks and Christians fled to villages. We moved to Zefanoz, where

my grandmother had an estate. It was a cold, rainy day in February. On reaching the

village we found both of Grandmother’s houses requisitioned by a prominent Turkish

official, Remzi Sami Bey. His uniformed orderlies had taken the keys from the

caretaker and were busy cleaning the buildings. His wife and children were expected

to arrive momentarily.

We stood in the rain, shelterless. It was revolting. But what could we do? To oppose

a government requisition was a crime punishable by death. We wondered whether his

wife belonged to the old bigoted or the new “enlightened” class of Turkish

women.

Happily she turned out to be of the latter. She was unveiled, which meant she was

emancipated and civilized. She and her two sons, riding on horseback, were

accompanied by a few soldiers. Pale, slender, chic, she was extremely attractive.

She told us that she was born and educated in Constantinople. We relaxed.

Her name was Selma Hanum. She apologized in exquisite Turkish phrases for the

inconvenience she had caused us, and she said she did not know the houses had been

requisitioned without their owner’s knowledge and consent. She was sorry. However,

because of her husband’s official position, which necessitated many important

conferences in their home with high German and Turkish officers, they had to live in

this village, which was close enough to the city, yet out of the reach of the

Russian guns. Perhaps we could rent to her the large house? Rent? We could hardly

believe our eats. She was a real lady. With mutual thanks and compliments an

agreement was reached.

She talked with us freely and without covering her face, for we had no menfolk with

us. Father had to remain in the city to keep his pharmacy open, as required by law,

and Uncle Leon was to join us in the village a few weeks later. She expressed the

wish, patting my head, that Onnik and I would play with her two sons, Mahmut Bey and

Shukri Bey. As their father was a bey, they were beys too, and she called them by

their titles. Both were fair, good-looking boys, in European clothes. We had never

played with Turkish children before, but now we shook hands and talked like friends.

Selma Hanum paid us a ceremonious visit, which we duly returned. After this exchange

of diplomatic courtesies, we became good neighbors, and Onnik and I played with

Shukri Bey and Mahmut Bey. Their mother would watch us approvingly. Mr. Ohanian was

also in the village, and she engaged him as Turkish tutor for her sons. I was very

happy because he was a poor man and had a family to support. We had no idea Turks

could be so nice. Selma Hanum won us over completely. In a few weeks the winter was

over. The crocus bloomed..

It is to the author's credit to

relate this example of the one Turk who was "so nice." I found this

statement to be a sad commentary: "We had never played with Turkish children

before." Because of segregation? Because of feelings of superiority?

|

| I believe in the

truth of eyewitness interviews from this

report covering the 1915 Van revolt. In the section entitled, "The

Pre-1915 Status of the Van Armenians & Relations with the Muslims," we

get accounts such as: 'Zahide Coskun of Koprukoy said: "We had Armenian

neighbours both in our village (at the time she was living in the village of Gollu)

and in the neighbouring villages. We got on with these neighbours of ours just as we

got on with the Muslims. Everything was good"...' I don't know what to make of

this picture of severe segregation that Surmelian presents. True, "Armenian

quarters" may have been separate in many villages. Yet, it's hard to fathom that

the Turks would be regarded as such an alien, unknown species, as Surmelian's story

indicates. |

[p. 73-74] I awoke one morning with the gay riot of

sparrows under the eaves of our roof. Onnik threw a pillow at me. I threw it back at

him, and we chased each other on all fours, growling and barking like dogs.

“Stop that racket !“ Mother cried. “You can take an example from Shukri and

Mahmut. See how gentlemanly, how well behaved they are.”

We had to agree that they were. We were pretty wild and rough compared to them. They

wore long pants, too, though they were not older than we.

“Onnik! Zaven !“ Shukri and Mahmut called us from the lawn, standing under the

windows of our bedroom. “Sabahunuz hayir olsun! May your morning be felicitous !“

“Sabahunuz hayir olsun!” we returned, leaning out the window.

Mother smiled. They were so glad to see us. It seemed they couldn’t get along

without us.

"Come on down, and let’s play tip-cat," Shukri begged. He sent a small

stick flying through the air with a blow of his bat. "See how I have improved

!"

"You certainly have," we agreed. ~We had taught them the game. We were

their only playmates in the village; they did not associate with other boys, not

even Turks.

(...)

I had planted some beans under an acacia tree, and dashed over to see if they had

sprouted. Clawing the earth back, I felt them with the tip of my finger. They were

firm. They had taken root!

"My beans are growing !" I shouted excitedly, and grabbing Mahmut whirled

around with him. He was happy too.

"We have sunk another English battleship," he said. "Father got the

news last night."

"Our soldiers in the Dardanelles are eating English chocolate," his

brother Shukri added, laughing.

But what was good news for them, was bad news for us. I became glum. Mahmut sang “Illeri!

Illeri!” and marched across the lawn. He was always playing soldier, like me.

But while I aspired to be another Napoleon, his idol was Enver Pasha. He maintained

that Enver Pasha was greater than Napoleon and would clean up Russia, England, and

France. I was careful not to betray my feelings too much, and did not argue with

him.

After breakfast we played tip-cat with them, and then watched the Turkish recruits

drilling on our lawn. Remzi Sami Bey had transformed part of our lawn into a drill

ground. The Christian soldiers were not given arms any more and were herded in labor

battalions.

----------

How mysterious. The Armenian

soldiers were given arms to begin with, which is odd if the idea had been to

exterminate the Armenians all along. Now why would you suppose the decision was made

to take these arms away? (Hint: "At the front the Armenians used blank

cartridges and deserted in droves.")

At least Surmelian treats the

"labor battalion hell" issue fairly, by acknowledging the other side of

the coin... a great rarity in Armenian propaganda (although he couldn't resist

adding another example of his own superiority, compared with the dim-witted Turks):

----------

[pp. 74-5] For them life in the Turkish Army

was hell. But even the Moslems suffered. I felt sorry for these recruits. They were

such a miserable, submissive lot, just resigned to their kismet. They never joked or

laughed. Some of them were barefooted. They lived on bean soup and brown bread, but

the soup was like dishwater, and lucky was the man who fished out a bean. They were

starving. This group was almost ready to go to the front; they had finally learned

which side was left, and which side right. The sergeants had an awful time teaching

them that. I knew the commands much better than they.

While we were watching them drill, and the air

was filled with the hoarse shouts of the sergeants, the telephone rang. Telephones

were strictly for high official use, and Remzi Sami Bey had installed one in the

large house. This particular call was for Shukri and Mahmut, and came from another

village. They ran to answer it, and then told us proudly that they had just talked

to the sons of the governor-general, who was coming to spend a week with them. Their

fathers were close personal friends.

The guests arrived in the afternoon, on horseback, with a few orderlies. I disliked

them intensely the minute I met them. The three sons had mean faces, and were loud

and spoiled. Shukri and Mahmut included us in all their plans for the week, but

their guests could barely hide their contempt for us. We were nothing but giaour

dogs in their eyes. We were afraid to antagonize them; otherwise we would have

preferred not to have anything to do with them. The youngest, about my age, was the

meanest. We played marbles and knucklebones, and he flew into a rage when he lost.

In the running game, “taking prisoner,” I purposely let him catch me a few

times, though I could run faster than he. When I caught him, he insisted he had not

crossed my boundary. We had an argument. I was willing to let him have his way,

since his father was governor-general and our lives were in his hands. I wanted to

be diplomatic, since we were living in dangerous times, but I lost my patience.

"Giaour dog, you can’t talk to me like that !" he shouted in my face.

"You don’t have many more days to live anyhow. We will cut your throats. We

will massacre all of you. We will not leave a single Armenian alive I" He moved

his hand across his throat and showed me how they would butcher us.

----------

Let's bear one thing in mind

with this anecdote: we're dealing with children. Children have a tendency to be

cruel, and these spoiled, mean Turkish kids sure sound like they were trouble.

Consider their governor dad was

getting all the lowdown on Armenian treachery, that Surmelian himself provided a

representation of, in his nine-year-old state. (ADDENDUM, 8-07: For example,

an Oct. 1914 telegram the governor wrote, featured in the "Trabzon Facts"

box below, and its original is here.) Imagine the headaches the armed Armenian rebels were

causing the beleaguered Ottoman army, from behind-the-lines. The dinner table

conversation in their household must not have held the traitorous Armenians in the

highest esteem. Of course these kids would have been influenced, and would have

treated poor little Leon with contempt. Among humans, this would be the normal

REACTION to treacherous ACTION.

Now let's add the factor that

these were kids, and mean-spirited ones at that. (Sons of the governor! Imagine the

superiority complex.) It's natural to assume, in creepy little kid-speak, that WE

WILL KILL YOU would be a natural outcome of the miserable situation.

Yet author Surmelian actually

takes this outburst as "extermination" evidence!

As if the governor... even if

he were made aware of secret extermination orders, assuming they were a reality...

would pass on such sensitive information to his little kids! (And his

"loud," big-mouthed kids, at that.)

I ask you, ladies and

gentlemen, is that not mind-boggling?

But here's where Surmelian

enters "unforgivable" territory:

After the spoiled brats make

such an ugly comment, little Leon Surmelian turns to his good friends, Shukri and

Mahmut ... and they respond with an embarrassed silence. Entirely in keeping with

their "gentlemanly" character, especially in the face of the other vicious

boys.

How does Surmelian interpret

this silence?

He indicates to the reader that

it's obvious Shukri and Mahmut have also been made aware of these extermination

orders!

Yes, these little boys...

seemingly devoid of prejudice, as children naturally would be before their parents

or other influences corrupt them.... these little boys who played such warm, loving

games with little Leon, are made out to be — in my opinion — worst

monsters than the governor's creepy kids, for knowing that their Armenian friend's

life would soon be kaput.

This is the nature of the evil

Turks, then... according to Leon Surmelian.

|

| The

"Genocide" begins |

[p. 80] ...[S]omehow news of events in Constantinople, Van, Erzurum and elsewhere in

Turkey reached us in Zefanoz. All the outstanding Armenian intellectuals in the capital,

hundreds of poets, journalists, teachers, doctors, lawyers, pharmacists, and even members

of the Ottoman parliament, had been rounded up by the police in one night and sent under

heavy guard to the interior, nobody knew exactly where. They had disappeared and had not

been heard from. In Van an Armenian uprising had taken place after their leaders were

treacherously seized and murdered by the governor-general Jevdet Bey, who was Enver Pasha’s

brother-in-law, and the entire Armenian community there was threatened by a general

massacre. The Turks were bombarding the Armenian quarters of Van from the fortress. The

Van Armenians were famous fighters and Uncle Leon was confident they would resist to the

last man.

In Trebizond the blow first fell on the Russian subjects, several of whom were in Zefanoz,

and we had relatives among them. They were summoned to the palace of the governor-general

to hear an "important message"—and never returned. We understood they were put

in boats and deported to Kerasund, in the custody of gendarmes and chetas.

----------

I had been lulled by the

"gentle, civilized" nature of what I hoped to be a rare, fair example of

"Armenian Oral History," but Leon Surmelian's treatment of Shukri and Mehmet

drove home for me that this is yet another exercise in Armenian propaganda. So it's hard

to take whatever Surmelian says seriously. Particularly when he informs his reader that

the ringleaders who had been rounded up had disappeared and had

not been heard from.. Even Peter Balakian provided a couple of

examples of survivors in his abominable "The Burning Tigris." According

to Balakian, they had escaped.... including his "action priest" relative. Or were they released, like the musician

Komitas, after a two-week imprisonment? No doubt most were executed, and there were likely

innocents among them, but there was a full-scale rebellion going on. Leaders had to plan

these rebellions, and the price for treason is a high one in any nation; particularly

during wartime... and particularly during a war when super-powered nations are at the

gates. (Incidentally, the Armenian who ratted out some of these leaders — Harootyoun Mugurditchian — was later assassinated.... by

none other than Talat Pasha's killer, Soghoman Tehlirian!

[The Armenian Review, Autumn 1950, pgs. 46-7]

And here we go again with the

blackening of that eternal Turkish villain, Jevdet Bey. (The one Balakian actually would

have us believe, from his "Tigris" work, nailed horseshoes on Armenian feet..)

Curiously, it was on the Armenians' very own "Date of Doom," April 24, that a

telegram was sent suggesting a "deportation." It was sent by Jevdet Bey, and the

"deportation" concerned the endangered Muslims in his district, not the

Armenians:

"Until now approximately

4,000 insurgent Armenians have been brought to the region from the vicinity. The rebels

are engaged in highway robbery, attack the neighbouring villages and burn them. It is

impossible to prevent this. Now many women and children are left homeless. It is not

possible nor suitable to relocate them in tribal villages in the vicinity. Would it be

convenient to begin sending them to the western provinces?"

Armenian propaganda loves to tell us

the Armenians were only defending themselves in Van, and Surmelian happily obliges in

repeating this lie. The fact is, this was one of several Van uprisings, the first one taking place only days after Russia had

declared war in late 1914. It was not the Armenians threatened with massacre, but the

Turks and Muslims... since the menfolk were all away, fighting on the multiple, desperate

wartime fronts. The well armed Armenians began their offensive on May 8, and started

burning down the Muslim quarters. Jevdet Bey had no choice but to order the evacuation of

Van, and Turkish defense forces left Van on May 17... whereupon the Armenians began to set

fire to the evacuated Turkish quarters ... clearing the way for Russian entry.

It is interesting that those of

Russian ethnicity were living in Trebizond and were also subjected to

"deportation." Since the lawless chetas (gangs) accompanied this move

(amazing the details a nine-year-old boy learned... and retained, for thirty years), we

can infer the heartless Turks must have murdered them all.

----------

About a week later a proclamation by the governor-general was posted in the streets of the

city and announced by town criers. Copies of it reached Zefanoz and Mr. Ohanian, our

instructor of Turkish, read and translated it to the anxious people who gathered around

him. He wiped his pincenez glasses with a silk handkerchief exactly as in our classroom

before he started reading that lengthy edict. It went like this:

Our Armenian fellow-countrymen, having allied themselves with the

enemies of the state and religion, and being in revolt against the government, are to be

deported to special districts in the interior and shall have to remain there for the

duration of the war.

We hereby order every Armenian in the province of

Trebizond to be ready to leave in one week, June 24 to July 1. Every Armenian without a

single exception is subject to this decree. Only those who are too ill and too old to walk

will be temporarily exempted from the deportation and taken care of in government

hospitals. Armenians from this day on are forbidden to sell anything and are allowed to

take with them on their journey only what they can carry with them. No carriages can be

supplied.

In spite of their ingratitude the government will not deny its Armenian subjects its usual

paternal care and protection, will keep their houses and stores under seal, and restore

them to their owners when they return from their temporary exile.

We are forced to take this extreme measure for the defense of the fatherland

as well as for the good and security of our misguided Armenian fellow-countrymen. If any

Armenian opposes this decision of the government by armed resistance or otherwise, or

tries to hide himself, he will be taken dead or alive. All those who hide an Armenian or

give him food, shelter or aid of any kind will be punished by hanging, whether they be

Moslems or Christians.

Mr. Ohanian wiped off the beads of perspiration that had sprung up on his scholarly brow.

The color was completely gone from his face.

"I devoted my life to the teaching of the Turkish language," he said in a voice

charged with emotion, "and now I have to read and translate a proclamation like

this."

People discussed the implications of this order and I listened eagerly.

"The Germans have deported thousands of Belgians, but this is not a mere copying of

German methods. This accursed government wants to destroy our nation."

"Calling us ungrateful when Armenians have built Turkey We have built the palaces in

which their bloody sultans live, we have built their greatest mosques, we have sewed their

clothes and made their shoes and treated their sick and even taught their children how to

read and write their own language. We have built and they have destroyed. And now the

Ittihad is going to solve the Armenian question by exiling all of us, men, women and

children."

"Where are they going to send us?"

"To the Arabian deserts. That’s where they are sending the Armenians of Erzurum. We

have to walk to Mosul and Baghdad." "It would take us at least four months to

reach Mosul."

"This is wartime and the government is disturbed by what has happened at Van, so

wants to remove the Armenian population farther away from the front as a military

necessity. I think, on the advice of the German high staff. We shall suffer, yes, but

deportation is better than massacre."

"What we should do is to escape to the mountains, as many of us as possible, and

fight our way to the Russian lines." This proposal thrilled me. Oh, boy, how I would

fight! "Don’t talk nonsense. It will be sheer suicide. Fight with what? Can we

muster up fifteen rifles?"

They argued pro and con. Uncle Leon summed up the discussion by saying out of the corner

of his mouth: "Whatever will happen will happen to us men." Meaning the

government’s intention was to kill the men, but merely deport the women and children.

And that seemed to be the general belief.

Uncle Leon was one of the few known revolutionaries in the village and being a marked man,

friends urged him to take his rifle and go join the band of peasant deserters in the

mountains, among whom was his cousin Barnak. But he shook his head:

"I can’t leave my mother alone."

"Don’t worry about me," Grandmother said. "I have lived long enough. You

run away and save yourself."

"I am going to stay with you no matter what happens."

----------

A few words on the proclamation. Yes,

it was an awful directive, to disrupt the lives of so many. (And let's bear in mind, it

was not only Armenians who were "deported" by the Government, but Turks as well.

One example, from the Palu region: "...the entire civil population, Turkish as

well Armenian, were sent away." Leslie Davis, The Slaughterhouse Province,

p. 104) Yet, given the treachery that Surmelian has given wonderful evidence of, and given

the desperate wartime situation, no other nation would have acted differently.

Arthur Tremaine Chester gave the following analogy, were a similar situation

to occur in the United States, and logically predicted the USA's "internal

enemies" would have been treated much worse. Nobody shed a tear for the Muslims the

Russians ruthlessly exiled during this period, even though the Muslims were not in revolt.

In fact, Enver Pasha preferred the Ottomans to adopt the Russian course, as this May 2, 1915 telegram specifies; he preferred

to truly "deport" (to move out of the country, and not around the

country) the Armenians. Would that have been the greater humanitarian course? (A tip:

Hovannisian has written some 150,000 Armenians who accompanied the Russian retreats died

of famine. Imagine what would have happened to these Armenians had they been cruelly

driven to Russian territory, without provisions and the care the

Ottomans had set aside for the Armenians.

As it were, an Armenian

representative reported to

Ambassador Morgenthau himself that half a million Armenians had "already settled down to business" and were

"earning their livings," by September of 1915... over two months after this

march from Trebizond. In another private communication that the contemptible ambassador

kept from his propagandistic "Story" book, Morgenthau was quoted (by Vahan

Cardashian, in a March 3, 1916 letter to Lord Bryce) as saying Armenians were found in

good numbers in almost all the interior cities of Turkey, and that the attitude of the

Government was passive. (The Armenian Review, Winter 1957, p. 107.)

Yet, Leon Surmelian will deceitfully

go on to make his reader believe extermination was the fate of the Armenians.

There were more exemptions granted to

classes of Armenians (such as Catholics and Protestants), but note how we are told above

that the sick and the old would be exempted. If the idea was to exterminate the Armenians,

why would this be? (The genocidal nation pro-Armenians love to compare with the Ottomans,

Nazi Germany, had a policy of euthanasia for its sick. Maybe Hitler got the idea from the

Armenians; from a Turkish proclamation in Davis' The

Slaughterhouse Province: In January and February 1915, many Moslem sick and injured

who were returning to their homes from the front, were pitilessly massacred in Armenian

villages through which they passed.)

----------

[p. 83] When in the evening Remzi Sami Bey, who had been extremely busy that week with

conferences in the city, returned to the village, a delegation of Armenian women headed by

Mother appealed to him to spare the women and children.

"We don’t know where to turn, whom to appeal to except you. You are our neighbor,

you know us," Mother said, blushing. Others, more frank and voluble, raised their

voices, half protesting, half begging him to exempt the women and children. At his request

this meeting took place on the lawn next to ours. His wife and sons kept discreetly out of

sight. Standing like a god before us the mighty bey listened to these appeals, and then

gave his official answer in a thundering voice.

"Ladies, Hanum effendiler! The Armenians of Van revolted to stab our heroic

army in its back, while the regiments of Armenian volunteers in the Russian army are

carrying on a war of extermination against us. We were obliged to withdraw from Van, and

the unprincipled traitors there who have taken up arms against their own government, have

committed terrible atrocities on the peaceful Turkish population."

He paused, surveyed the crowd before him, and throwing back his big handsome head roared

louder. "The Russians have set up an Armenian government in Van under the presidency

of the chief of those bloodthirsty fiends, and the very existence of our fatherland is

threatened! We are very sorry, but we have to remove all Armenians without exception to

the interior in order to protect the rear of our army. I give you my word of honor that

our gendarmes will protect you on your way and no harm whatever will come to you. The

Ottoman State is magnanimous. After the war, which cannot but end by the complete victory

of our arms, you will be permitted to return to your homes and receive back all your

properties and goods. The day will come when you will realize that Russia and your own

comitadjis are your worst enemies, and you will thank the government for securing the

freedom and safety of the country and your own future happiness and prosperity by the

expedience of temporary exile."

He turned on his heel, and strode back to his house.

For some reason I visualized the Armenians of Van as human warriors living and battling in

a red sky. Oh, if I could only be at Van! If I could somehow fly on a fiery horse to those

red clouds. The word “Van” constantly hammered in my mind as I lay in bed that night,

unable to sleep.

I find it highly interesting that Leon Surmelian

would include the above speech; he must have done so with a wink, assuming his reader will

realize that everything Remzi Sami Bey thundered was a lie. (Particularly with Surmelian's

upcoming chapter dealing with the "deportation," where he leaves no doubt the

aim was extermination.) Yet I get the strangest feeling, Surmelian's conscience (given his

"gentle, civilized" style) chose to give a little "equal time" here.

Everything the Bey promised was the truth — at least truth that he believed in.

The reasons he provided for the Armenians' removal

were right on the button. Atrocities were committed after the Van Armenians had won, and

the existence of the "fatherland" (is that Surmelian's "Nazi"

parallel at work again? Surely he knew the Turkish term would have been "motherland")

was highly threatened.

I'm sure Remzi Sami Bey believed the gendarmes would

have protected the Armenians, and despite the horrors Surmelian will tell us that they

inflicted, perhaps they did. The Bey was 100% truthful in conveying the fact that the

relocation was of a temporary nature, the state did issue orders safeguarding Armenian

property (even though no doubt there were abuses... but these genuine orders were not

issued for show), and the Armenians were allowed

to return.

The one area in which he erred (aside from,

probably, the gendarmes' behavior) was when he believed the Armenians will realize the

error of their ways, and concede they were the dupes and

pawns of the Russians and the horrible revolutionary leaders who did not care for their own people. Fat chance.

The next day all the Armenians in the village were busy preparing for departure. Women and

girls sewed knapsacks, breeches and caps as if they were going on a vacation. Mother hoped

we might be exempted from the deportation, Father being a pharmacist. The government

surely could not afford to deport him when epidemic diseases killed more soldiers than

enemy bullets and pharmacists were even scarcer than doctors. We were quite certain Father

would attach himself to an army hospital or do something like that to save us. There were

many influential Turks among his friends and clients, and he was known to be a

conservative man, opposed to our political parties.

If Surmelian Senior was the one voice of sanity

among his people, a true injustice was committed if he was not granted an exemption.

Particularly if a lot of influential Turks knew him, and particularly since his profession

was a valuable one. (Exemptions were granted, including for those who were soldiers and

their families... especially those who worked in the medics corps, as we learned was the

assigned area for Vertanes; I don't recall what his fate was, if

provided.)

Perhaps the authorities decided the exemption would

have been too risky, if they had gotten wind of what a traitor Surmelian Junior happened

to be.

|

FUN

TRABZON ("Trebizond") FACTS

Let's take a look at other

perspectives regarding Surmelian's residence!

Anti-Armenian treatment in Trabzon, circa

1880:

The British Consul in Trabzon,

Alfred Bliotti, affirmed that the administration of the eastern provinces was indeed

oppressive; this, however, was not directed specifically at Armenians, but, rather,

was a general maladministration. He further stated that Muslims were more oppressed by

this administration, for the non-Muslims could voice their complaints through the

Consuls, whereas there was nobody the Muslims could complain to. Moreover, the Consuls

did not see the necessity of speaking up against the treatment of Muslims.

So it wasn't just the Armenians

who were "persecuted"!

Trabzon was the headquarters of the Dashnak

Party

According to Louise Nalbandian, Trabzon was chosen as the center of the terrorist Dashnak party

in 1890. Most leaders resided in Tiflis.

Armenian Rebels Within the Trabzon Province

The Governor of Trabzon,

Jemal Azmi Bey, in a message he sent to the Ministry of the Interior on 8 October

1914, stated that "A band of 800 people comprising the Ottoman and Russian

Armenians in Russia, has been armed by the Russians, and sent to the vicinity of

Artvin. We have been informed that they will spread out between Artvin and Ardanuch,

that their number will be increased to 7,000, and that they will be used to disturb

security within the Ottoman country."

This report comes roughly a month

before war began. Perhaps the Armenian resistance in Trabzon was not as

inconsequential as Surmelian indicated. (Could this have been the governor with the

two demon kids? Jemal Azmi Bey would be murdered soon after the war by an Armenian

"Nemesis" assassin.) (ADDENDUM, 8-07: The original document.)

An Ottoman "Deportation" Order:

On 4 July 1915 (21 June 1331), the Ministry of

the Interior sent a message to the provinces of Trabzon,

Sivas, Diyarbekir and Elaziz, and to the sanjak of Janik: "It is ordered that the

Armenians and their families whom the Government considers dangerous be removed, and

that the merchants and artisans who are harmless be retained but that they be required

to move out of their towns within the province."

So the official order from Talat

Pasha regarding the Armenians of Trabzon was that not all the Armenians of Trabzon

were to be subjected for relocation, the opposite of Surmelian's claims. Then again,

Surmelian has written that his "Every Armenian without a single exception is

subject to this decree" was already in effect, June 24 to July 1... meaning that

there were no longer any Armenians left in the entire province (save for the too old

and sick) by July 4, since Surmelian's version affected "every Armenian in the

province of Trebizond." (ADDENDUM, 8-07: Other details of this document.)

(The above information is from K.

Gurun's "The Armenian File.")

|

[p. 85-87] We did not want the Turks to gather the

crops planted by Armenian peasants. Then we broke into the orchard of Mother’s

aunt. Her sour cherries were ripe, and we devoured fistfuls of them. She appeared in

the doorway of her cottage, a severe old dame dressed in black.

“Hey! You good-for-nothing rascals! Get out of my orchard!” she cried. “I was

keeping those cherries to make jam.”

“Jam?” We burst out laughing.

“Do you want the Turks to come and eat them?” I asked her, swinging merrily on

top of a tree.

She realized that this was not an ordinary cherry season, that in a few days we

would be on our way to Mesopotamia, and she need not worry any more about serving

her guests the sour-cherry sherbet of which she was so proud. And, shrugging her

shoulders, she went in.

On the afternoon of that same hectic day Mother received a note from Father. Unlike

the other families we did not make any preparations as we did not know what Father

wanted us to do. His note was laconic and gave us no hope of a possible exemption.

He asked us to take only a few blankets with us and return to the city, to Aunt

Shoghagat’s house.

We looked like a group of forlorn refugees as we left Zefanoz. We did not lock the

door of our house, knowing the futility of doing so. Turkish peasants, sensing the

rich booty in store for them, had already gathered like vultures around the village.

Since we were forbidden to sell anything and had to travel to Mesopotamia on foot

our possessions were of no earthly use to us anyhow. We were not so naive as to

believe the government would keep them under seal, in spite of Remzi Sami Bey’s

assurances.

What I regretted most leaving behind me was my potted pink carnation. I watered it

for the last time and hid it on the roof. I would have asked Shukri and Mahmut to

water and take care of it during my absence, and also to be kind to my beans, but

their door and windows were closed again. All departures make one not only sad, but

forgiving. I wanted to shake their hands and say good-bye, but they did not come out

of their house.

On our way back to Trebizond we met a Turkish family, obviously going to a village

for their summer vacation. The women rode astride on donkeys holding their little

ones in their laps, while the men jogged along the dusty road, big checkered

handkerchiefs tied around their perspiring necks. We were curious to know how the

rank and file of the Turks, families like this one, took the deportation order. The

women were veiled and we could not see their expressions, but the men seemed to tell

us with their sad eyes: “Why should such things happen? Isn’t there room enough

for all of us to live in peace? You have done us no harm, and we wish you no harm.

Allah be with you.”

The city was dead. Practically all the stores were closed, the streets deserted. Now

and then a Turk passed by, grave and silent. We almost wept when we saw the shutters

of our pharmacy drawn too, in broad daylight. That was something we had never seen

before. Poor Father! What was he thinking of, what was he doing, now that they had

taken his pharmacy away from him?

Aunt Shoghagat, Father’s sister, older than Aunt Azniv, lived in a Turkish ward.

We went down a very narrow street that descended like a winding stairway to the

beach, a ghostly lane impervious to the sun, cool as caverns and smelling of the

refuse of the sea. Life in this Turkish street was so very different, so somber and

mysterious, with latticed windows and exhortations from the Koran carved over the

façade of an old public fountain. Here we saw a few women fill their brass ewers,

different in shape from those Christians used. They had longer and narrower necks.

These women were shrouded and bundled in the mystery of the East, and only their

fingertips tinged with henna were uncovered. As they walked before us

clitter-clattering in their clogs we could not tell whether they were toothless old

hags or beautiful girls and brides.

-----------

To Surmelian's credit, we get

an idea the Turkish "rank and file" were not filled with hatred for their

Armenian neighbors. Quite the opposite impression from what Prosecutor Vahakn

Dadrian would have us believe, when he stated,

" There was massive, popular participation in the atrocities."

|

| "The Highway of Death" |

This chapter is the one where Surmelian pulled

out the stops. So strongly propagandistic, I'll have to give a recap of the worst moments.

Once again, no one is denying the Armenians endured

great hardship, even at the hands of the sometimes low-quality gendarmes who were assigned

to guard them. (Although there were instances when gendarmes lost their lives, trying to

defend the Armenians from Arab bandits and other nogoodniks. Example 1: Amb.

Morgenthau; Example 2: Tehlirian trial. There

have been even the very rare cases of Armenians testifying that the gendarmes did their