|

|

Mary Louise Graffam was a

missionary who was written about in a loving manner (the author happened to be

her brother-in-law) in Armenian

Affairs Magazine. I conducted a search to learn more about her, and

the "Internet" claim-to-fame of the missionary thus far is that she

has been identified as a "witness to genocide" in 2003's America

and the Armenian genocide of 1915, edited by Jay ("The Great War") Winter. Witness

to genocide, or witness to suffering?

|

|

Genocide

advocate Jay Winter ("The Great War") |

As Sam Weems wrote, "It appears,

the Armenians consider every Armenian who was removed to be a victim of

genocide. Relocation is not genocide." That goes for blatantly

one-sided pro-Armenians such as Jay Winter.

The remarkable

revelation made below is that Graffam (who died of cancer in 1921) asked

permission of the Sivas Governor to accompany her

Armenian friends who were being relocated, and permission was granted. That's

a strange way to run an extermination campaign, to allow a hostile foreign

witness to tag along. In addition, she continued to treat Turkish soldiers

(very much to her credit, recognizing non-Christians as human beings) in

military hospitals. If she believed there were an extermination campaign, why

would she have lent a hand to the evil forces responsible? That makes no sense

whatsoever.

My curiosity was aroused

as to what sort of a "genocide witness" the missionary made, and I

analyzed her chapter from the aforementioned book, as well. (Where I learned

of her ulterior motives for treating Turks... her reasons were not as

"pure-hearted" as I initially thought from the first article. She

also — at least at the time of the events — lets the Ottoman

government completely off the hook!)

There is also speculation

that she might have worked undercover for American intelligence.

|

|

|

| Mary Louise Graffam |

Armenian Affairs, Winter

1949-1950, Vol. I, No. 1, pp. 62-65

Mary Louise Graffam By ERNEST C. PARTRIDGE

ONE of the most interesting characters I have known was Mary Louise

Graffarn, the missionary of the American Board of Missions. who became famous in the first

World War as the only American who trekked across Asia Minor in the early spring of 1915

during the deportation of the Armenians for several weeks with the girls of her school and

the several hundred members of the Armenian Protestant Church of Sivas.

I first came to know Polly Graffam in her freshman year at Oberlin

College, where we worked at the same college boarding house, she earning her board washing

dishes and I waiting on tables. We became acquainted helping each other in the rush of

finishing work and getting to class on time. The next year her younger sister joined us.

After my seminary course Winona and I were married and after a two years’ pastorate, we

went to Sivas, an interior station in Turkey for a life of service in the education of

Armenians. One year later, the position of principal of our girls’ high school being

vacant, Mary joined us, and gave the following twenty years to devoted service for the

people of Turkey.

The striking quality of Mary Graffam was her versatility. She did

well anything she undertook. She was a successful teacher and a capable administrator. For

thirteen years to the outbreak of World War I her activity was largely in educational

work, but she never limited herself to the school. Soon after her arrival in Sivas and

before she could read Armenian with ease she had to play the organ for the church service.

She could do this acceptably but she could not read the words of the hymn fast enough to

keep up with the music. Our teachers used to tell stories of her mistakes. a favorite

pastime of those close to new missionaries. One mistake they still speak of was on the

line of the gospel hymn, "leaving our cares we fly away and are at rest." The

words sorrows and hens are much alike, so she was singing, "leaving our chickens we

fly away." Another time during her early months in school she had introduced a young

man into the girls’ high school to teach singing, an unheard of thing then for a man to

teach in a girls’ school. She was present as chaperon. The beardless teacher called for

an eraser. And she calling a pupil, and confusing two words much alike, surpich and

saprich, called for a barber for the young man. This teacher, by the way, was the

distinguished Western Electric engineer, Dr. Garabed Paelian. But things like this never

fazed her. in every circumstance she tried to do her best and came through somehow.

Polly Graffam was very practical. She was a good seamstress, and

made many clothes for herself and her sister. During her early years in Sivas she trained

an Armenian tailor to make ladies’ dresses and coats, and for years he did most of the

work for our American ladies under her supervision. She had a good deal of talent in

languages, was a good student of Latin and Greek in college. A summer vacation in

Switzerland to recuperate from a severe case of typhoid gave her the opportunity to

acquire a speaking knowledge of French, which stood her in good stead during the years of

the first World War, when she was able to help French and other foreign officers and

civilians interned in her city. Her best foreign language was Armenian, but while in

military hospital work she acquired a speaking knowledge of Turkish. She was thanked by

the British and French governments for her service to their people, decorated by the

Turkish government for her service to soldiers and civilians. She was given an honorary

degree by her Alma Mater for humanitarian service during the war.

|

A Fun Fact About

Sivas:

"...[D]uring the Sykes-Picot

negotiations, Russia had insisted that Sivas and Lesser Armenia should go to

France and in return she should get the Kurdish populated Hakkiari-Mush in the east.

The reason had been Tsarist Russia’s desire to have ‘as few Armenians as

possible’ in the Russian territory and to be relieved of Armenian ‘nationalist

responsibilities’."

Akaby Nassibian, “Britain and the Armenian Question,

1915-1923,” 1984, p. 108

|

Although she had no special training in financial

matters, in the crisis of 1913-1914, when no one else seemed to have time for

accounts, she took over the station treasury. When in the early winter she joined a

party to Erzroum near the Russian front, as a volunteer Red Cross worker in the

Turkish army hospitals, she dumped her accounts on my desk, and I had the surprising

experience for the only time in my life of getting a balance sheet the first time.

During the winter of 1914 a typhus epidemic broke

in the Turkish army on the Russian front, 200 miles north from our city. An army

medical inspector sent from Constantinople told me after his trip that 1,000 men a

day for the preceding 60 days had died of the disease, on the road up to the front.

In this crisis our missionary physician, Doctor Clark, responded to a call from Army

hospitals in that city. In addition to the Doctor the party included our

American-born nurse, Mrs. Sewny, a Swiss nurse, Miss Zenger, Miss Graffam and a

pharmacist. These people spent the winter scattered in the military hospitals of the

city. On arrival there word came that Mrs. Sewny’s husband, an army doctor, was

dying in a village near the front several hours’ ride away. The two ladies started

off at once on horseback in the deep snow, to find the doctor in a collapse

following typhus, from which he died the next day. With the aid of a Turkish soldier

they made a box out of the doors of the cabin and brought the body on a packsaddle

back to burial in the cemetery in Erzeroum. There Miss Graffam was assigned as

manager of a hospital for Turkish officers, many of whom had frozen feet. This was a

small institution under the patronage of a group of ladies, wives of the mayor and

high ranking officers. Her experiences that winter would fill a book.

With the approach of spring and the persistent

rumors of deportations of the Armenians, Miss Zenger was anxious to return to Sivas

to look after her orphans, so she and Mary Graffam started back home. Khans, 1 where they stopped at nights. were. full of sick soldiers, and

every morning under the wagons in the enclosure they would see bodies of men who had

died during the night. About a third of the way to Sivas Miss Zenger was taken with

a severe case of typhus and died and was buried in the city of Erzingan. Fearing the

same fate might befall her we sent out two of our teachers to meet her. When they

met she was riding in a one horse araba 2 with a

decrepit horse, sitting in the rain under a tarpaulin. She was very worn out and

fatigued but received no permanent injury from the wracking experiences of the

winter.

===========

1 Inns.

2 Cart.

|

| |

In the meantime plans for the deportations of all Armenians

followed in this manner. All weapons of every kind, even pocket knives were collected on

the plea that they were needed b the army, but this collection affected only the Armenian

population. A little later 1,000 Armenian men and women were thrown into prison, and thus

the 25,000 Armenians in the city were deprived of all weapons and the best of its male

leadership. After the deportation was completed these men were taken out of the city,

compelled to dig their own graves and then knocked on the head, stripped and buried. Among

these men were many of our friends of years. The whole faculty of Sivas Teachers College

were thus murdered, either here or on the road. Among them were two men of fine education

and talent — Roupen Racubian, a post graduate student with two years’ work at

Columbia, our professor of education, and Michael Frengulian, a graduate of Oberlin

College, our teacher of sciences.

To return to the deportation, I was assured by the Governor of the

province and the Commanding General of the army at Sivas that this was an agricultural

colonization scheme, that the people were to be moved under protection of the army, which

was to supply them with army rations on the road. We hoped this was true but did not for a

moment believe it. When the deportations began, Mary Graffam asked permission of the

Governor to go with her pupils and friends; and much to our surprise it was permitted. She

took with her my saddle horse and two wagons, one loaded with flour for food, and the

other for giving short lifts for those who fell by the wayside. After several days on the

road the men were taken away, and no one of them was ever heard of again. After several

weeks of this trek she was ordered to return to Sivas, which she did, the last few hours,

driving the carriage when they took her driver away. In the meantime, as our educational

work had been entirely disrupted, it was decided that our family should return to America

for an overdue furlough, in order to be ready to return after the war and gather up the

broken remnants of our work.

For some months, Dr. Clark arid his associates were busily occupied

with medical work in our hospital, doing Red Cross work for sick soldiers, and caring for

the orphans who had not been deported. Several months later, as the Russian army was

moving towards Sivas, all the members of our station were ordered out. Miss Graffam was

finally given permission to remain with one companion, her associate. Mary Fowle. She died

of typhus. and for about two years Mary Graffam was the only foreigner in the city,

excepting a few Frenchmen and Englishmen. She had a group of girl teachers and older

orphans, who at the time of the deportations were working in our hospital. These were

given the choice of going on the road with the deportees or remaining in medical work,

with no guarantee on our part of our ability to protect them. Toward the end of the war it

is said there were 5,000 patients in the military hospitals of the city, many typhus

patients. and the head nurses were her girls. It can be said to the credit of the Turkish

doctors that they protected these nurses and no indignity was experienced by any of them.

|

|

Very soon after the Armistice, the Armenians who had lived

in this territory and all the way up to the Black Sea, who had survived began to

trek back, and then Mary Graffam with the help of her girls, began a new era of

expanding relief work. She had done such work as much as she could for straggling

Armenians, but now it became a major problem. For several months after the Armistice

she managed this growing burden. I reached Sivas just before Easter, 1919, and found

her with several hundred orphans, and the job of giving a pittance of bread relief

to some 3,000 women and children. In the course of a few weeks, with the arrival

from America of volunteer relief workers, I was in charge of a Near East Relief

staff which included 17 American workers, a physician, three nurses, and orphanage

and industrial workers.

It was definitely planned that, as soon as she could put her

wartime accounts into shape Mary Graffam should return home for a long overdue

vacation. But I had the misfortune to break my arm cranking a car, and not having a

chauffeur, got run down, developed a case of chronic appendicitis, and was sent to

Constantinople for an operation. When finally I came home for a surgical operation

and a rest, Mary was loathe to leave her charges. She said she had seen all the

agony, and now she wanted to stay on and see things build up again. So she tried to

stick it out, and finally died in Sivas from an overworked heart, following an

operation for cancer.

Mary Graffam’s was an active and very useful life, which she

enjoyed and to which she gave herself fully. There was none of the awareness of a

martyr’s spirit in her, but she was just as truly a martyr as those Armenian

pupils and friends whom she had accompanied to Mesopotamia and helped to lighten the

burdens and sufferings on the road to their Golgotha.

|

| More on Mary Graffam |

Before we move on to our analysis of the

"Witness to Genocide" chapter of America and the Armenian genocide of

1915, let's check out a few other Graffam references from other writers in that

book.

Suzanne E. Moranian provides the following in her

"American missionary relief efforts" chapter (p. 190):

"...[N]umerous

American missionaries serving in Turkey received warnings that the Armenians were in

danger before Turkey entered the war in November 1914. In September of that year, a

German army Colonel visited American evangelist Mary L. Graffam in Turkey. "He

was a Christian, although a German," Graffam explained, "and he tried to

warn us of things which might take place in the coming summer; this showing that the

deportations were planned as early as this." The Colonel told her that "a

certain fate was in store for all Armenians, but if the Germans were in the country,

there would be no massacres." (Source: Mary L. Graffam, "Miss Graffam's

Own Story," 28 June 1919, ABC 16.5, vol. 6, no. 262, ABCFM archives.

Graffam related the above in 1919, through a stenographer, according to Billington

Harper's chapter.)

Wishful thinking on the part of

this supposed German that his people's presence would prevent the massacres that

followed... on both sides.

Here we are getting a taste of

what an unreliable witness Mary Graffam was. The missionaries stopped at nothing to

pass on the stories of their beloved Armenians, and were not above making stories up

themselves. Why? It was their Godly duty to vilify the Turk, clearly spelled out in

their prayers. The hearsay we are being asked to accept here from an unnamed German

is that the resettlement policy was a done deal, even before the war started. As if

such a Herculean and expensive effort would take priority over what was most

important: the defense of the motherland in the face of three merciless superpowers

that would hit the ailing empire from all sides, making good on the secret treaties

they had planned between themselves.

We know from the progression of

events of real history that the Ottomans looked the other way (as far as taking

drastic action) regarding the wave of Armenian rebellions for as long as possible.

As the military situation grew more desperate, the first consideration of moving the

Armenian community out came with this May

2, 1915 telegram.

|

...[T]he general

Congress of Dashnakstsutiun, sitting in Erzerum in the autumn of 1914, had been

offered autonomy by Turkish emissaries, if it would actually assist Turkey in

the war.

Akaby Nassibian, “Britain and the Armenian

Question, 1915-1923,” 1984, p. 107; in other words, the Turks were hoping

to enlist the aid of their own Armenian citizens in the desperate

battle-for-survival to follow, where every able-bodied man was needed. Yet, before

the autumn of 1914 (if the mysterious German officer visited prior to September

22, when it was still summer), the Ottomans were planning the

"deportation" and potential extermination of the Armenians they so

desperately needed. |

So Mary Graffam is attempting

to have us believe that the fate of the Armenians was all pre-determined by the

government. However, as you'll read further, Mary Graffam herself let the

government off the hook. That's a significant contradiction.

We get an idea of

Graffam's extremism from Richard Hovannisian's "US post war commission" chapter (p.

262):

"No witness advocated Armenian independence more fervently than

Mary Louise Graffam, a long-time Oberlin missionary and teacher at Sivas (Sepastia).

As a witness to the genocidal atrocities, she told the (King-Crane) Commission that to

leave the Armenians with the Turks would be "beyond human imagination."

Sounds like Graffam would have

found agreement with British Colonel Rawlinson, when he was quoted by Robert Dunn

(in World Alive, A Personal Story, 1952, p. 358) as having said:

"'An Armenia without

Armenians! Turks under Christian rule?' His lips smacked in irony under the droopy

red moustache. 'That's bloodshed — just Smyrna over again on a bigger

scale.'"

Of course, Rawlinson was

referring to Turks living under ethnic-cleansing Armenians as being "beyond

human imagination," arguing against the mandate that would have insured

Armenian independence. Yet Graffam only reserved sympathy for the Armenians, in

loyal missionary style... an attitude no true Christian would stomach.

Hovannisian also wrote (p.

268):

"Harbord was told by Dr. Ernest Partridge and

his sister-in-law Mary Louise Graffam that, of the nearly 200,000 Armenians of the (Sivas)

province, only about 10,000 survived and these in a completely servile status."

(To supplement the above,

"Miss Graffam's Own Story" [1919] tells us: "Out of 30,000 people

there are about 3,000 left." [Referring to Sivas, the city.] The Armenian

Patriarch provided a complete Sivas total of 16,000, from his 1921 report to the

British. The pre-war [1912] population for the province was 182,912, according to

McCarthy, up from Capt. Norman's 132,307 in 1895.)

(Even the missionaries didn't

go as overboard as U.S. Consul madman J. B. Jackson, who — as Peter Balakian

gleefully repeated in his "Burning

Tigris" — reported only 5,000 emaciated and sick women and

children were the only survivors from the Armenian population of Sivas, where over

300,000 souls had once lived.)

Missionaries like Graffam had

clear sailing with the Christian sympathizers heading the King-Crane and Harbord

Commissions. Note how she and her missionary relative could have had no authentic

idea as to how many Armenians had actually survived; throwing out a figure that was

only 5% of the original population certainly worked to evoke better sympathy,

Partridge himself documented how

Armenians were returning in droves after war's end, which would have been highly

unlikely had such a small percentage survived. (Particularly if we keep in mind many

survivors chose not to return, or had escaped the resettlement in the first place,

moving to other regions on their own accord... such as 50,000 to Iran, and 500,000

to Transcaucasia, according to Hovannisian. Of an original pre-war population of 1.5

million overall, the Patriarch himself recorded up to 644,900 were in what remained

of the empire, after war's end and before Sèvres.)

Bearing false witness against

their neighbor came naturally to missionaries like Graffam. This sin was justified

in their minds, probably, as long as the greater Christian good could be

accomplished.

What might be described as a

greater sin in this day and age is that there are authors who still point to

missionary testimony as valid today... such as the authors of America and the

Armenian genocide of 1915, a propaganda book edited by Jay Winter.

|

| Witness to Genocide,

or Witness to Suffering? |

"Mary Louise Graffam: witness to genocide" is

Susan Billington Harper's contribution to the book mentioned above.

The Armenians have succeeded in planting their "colonists"

(in Hovannisian's and other Armenians' word) throughout Western society to better accept

the warped Armenian version of events as the common wisdom... sort of like in Invasion

of the Body Snatchers, these single-minded "Pod People" are now present in

all walks of life. An Armenian editor resides at National Geographic Magazine, for

example. When articles on Armenia surface, readers get hit with the usual propaganda, such

as 1.5 million exterminated Armenians.

The mission of "Pod People" is to convert others into

being similar Pod People.

One, Dr. Levon Andoyan, has infiltrated the United States

government's greatest harbinger of truth, the Library of Congress ("LoC"). It's

shocking that Armenian propaganda litters the web site of the LoC itself. The head

librarian since 1987, James H. Billington, is solidly in the Armenians' corner.

Unthinkable, when one considers his position should entail the very essence of

impartiality. One wonders whether his mind was corrupted through the prevalence of

Armenian propaganda earlier in life, or whether Armenians in the LoC whispered in his ear

and poisoned his mind. Regardless, Billington has become such an apologist for the

Armenians, he actually tarnished the glorious name of the Library of Congress as a

co-sponsor of a Sept. 2000 Armenian conference that resulted in the book, America and

the Armenian genocide of 1915. (The driving force was the Armenian National Institute,

headed by Rouben Adalian, who has no tolerance

for deviation from the Armenian line... no matter how minor, even by fellow Armenians. Can

you imagine? As if such a conference had any chance of being objective, and Billington

incredibly allowed the Library of Congress to get mixed up with such an unscholarly

undertaking.)

An appreciation for Armenian propaganda sadly running in the family,

the author of the Graffam piece is Billington's own daughter, Susan Billington Harper.

|

...[M]issionaries ... often felt they had become do-it-yourself

diplomats.

"Protestant Diplomacy and the Near

East," Joseph L. Grabill, 1971

|

Billington Harper provides the background on her

subject:

On 14 August 1901, Mary Louise

Graffam, a shy teacher from the National Cathedral School for Girls in Washington,

D.C., left Boston for a new life as an educational missionary for the American Board

of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM) in Ottoman Turkey. She embarked on

what promised to be a fairly conventional missionary career as the head of Female

Education in the Near Eastern mission post of Sivas, an established American mission

station. Little did she know that she would be thrust, instead, into the horrors of

twentieth-century warfare and would become a first-hand witness to genocide

conducted by a government against a portion of its own people.

The author is not happy about Graffam's current

obscurity:

Surprisingly no serious

account, let alone major biography, of Graffam has ever appeared, despite the

existence of numerous unpublished documents, oral and written histories in Armenian,

scattered primary source materials as well as general works on the Armenian Genocide

and missionary history that mention her heroic resistance to the massacres... This

neglect is particularly startling since she was a celebrated figure in the United

States during and after the First World War, not only among missionaries but also

among government officials and the general public. (The

footnote credits a multitude of Armenian sources, and a debt of gratitude is

included for Levon Avdoyan, Ara Sarafian, and Dr. Osgan Kechian of the Pan Sebastia

Rehabilitation Union, Inc.)

As with many biographers, I'd presume

Billington Harper began to see her subject through rose-colored glasses, and would

be hard pressed to accept that Graffam's claims could be less than the gospel truth.

I'd suspect the reason why no one glorified Graffam among the ranks of serious

scholars in later years is because ... she was a missionary. Missionaries cannot be

accepted as reliable sources because their beliefs are staked on faith, and not

reality. Exactly as what lies at the core of Armenian genocide advocates; genuine

history must be passed over in the interest of maintaining the myth of innocence for

Armenians, and the image of barbarism for the Turks. In short, bigotry is a driving

force among both missionaries and "Armenian genocide" advocates.

Regardless, it doesn't seem fair for Graffam to

have been so forgotten these many years later. Such an unrelenting champion of the

Armenian cause should have been practically deified by the Armenians, for those who

hold "gratitude" high as a value. (After six-to-eight centuries of

prosperity among the Turks, alas, it was this lack of gratitude that caused the

Armenians to rebel in their Ottoman nation's darkest hour. Armenians would go on to

attack even their greatest friends, such as Reverend Barton and President Wilson.)

|

|

Missionary Mary Louise

Graffam |

General Harbord, whose Christian-sympathizing

mind was further corrupted by Graffam, gushed over her as follows: "It is no

disparagement of other zealous and efficient missionaries to say that Miss Mary

Graffam is the outstanding missionary figure in this part of Asia . . . [She has

played] a part in the stirring events of the last six years which has probably never

been equaled by any other woman in the chronicles of missionary effort."

("Investigating Turkey and Trans-Caucasia," Harbord, 1920.)

(I find it interesting that Harbord used the

word "zealous" as a positive trait. Is that a good thing, to be a zealot?

It's surely an appropriate word for a missionary, giving up all in life for the

purpose of faith; to the extent of moving to a faraway corner of the world.)

Billington Harper tells us open evangelization

among Muslims was forbidden by law, and that "the ABCFM

had earlier adopted an indirect strategy that focused primarily on the education of

Armenian and Greek Christian populations. The implicit longer-term goal was to

increase the faith and witness of indigenous Christian populations so that they

would become motivated themselves to spread the faith to Muslims."

Graffam's colleague in Sivas, Henry Holbrook wrote, shortly after his arrival in

1913: "It is almost maddening to be actually here in the heart of the Moslem

world — to whose crying appeal we consecrated our lives ... — and yet be forced

to realize that there is at present practically nothing we can do directly for these

young Turks. In the present condition of the country anything like active

anti-Moslem propaganda would be a dreadful blunder — the Moslem world will never

be won by militant methods but only by infinite patience and love."

The missionaries had a curious way of

exhibiting this "love."

Graffam first tried to get into the business of

altering others' lives in 1895, attempting to gain a post in Japan doing

"direct evangelistic or missionary work rather than teaching in a school,"

an educational role she soon had to accept, resigning herself to try and get to the

hearts of Muslims in indirect fashion. As for Holbrook, we're informed "his expectation of a long and peaceful career as an educator of

young Armenian and Greek children was dashed when he was brutally and mysteriously

murdered in 1913 by Turkish bandits." The contrast between

"good" and "evil" is clearly established with Billington

Harper's phrasing; I guess the implication (with the word, "mysteriously")

is that the Turkish bandits (perhaps Graffam was also an "eyewitness" to

this mini-genocide; otherwise, how can we be sure of the identity of the killers?)

is that the bad Turks snuffed out the missionary's life because he was a Christian.

Background on our missionary heroine: "Mary Louise Graffam was born in the small town of Monson, Maine, and

moved to Andover, Massachusetts, at the age of five. She was raised with a younger

sister, Winona, in a Christian home - probably Congregational.". She

experienced a "spiritual awakening at the age of fourteen,"

and "decided to become a foreign missionary during her

freshman year at Oberlin College," a missionary training college from

which she graduated in 1894 (and for which Graffam had to pay off her college debts

by working as a high-school teacher for six years, postponing her missionary dreams

in Japan. Shouldn't such education have been free, or close to it? As if

missionaries didn't sacrifice everthing else in their lives, as soldiers for their

cause.) Graffam was thirty-years old, 5 feet 7, 127 pounds and in good health when

the missionary offer came through in 1901. She would spend the remaining twenty

years of her life (save for a brief U.S. visit in 1909-10, which she devoted to

further service for Armenians; see below) in the city of Sivas, "composed of roughly 30,000 Armenians within a total population of

75,000." (Since Billington Harper prefers to rely on pro-Armenian

sources, perhaps these figures were provided by the Patriarch.)

(P. 220:) Graffam

contracted a serious case of typhoid in 1903, from which she recovered in

Switzerland, and the mission school struggled from 1909 to cope with declining

enrollments caused by a serious famine and, later, an outbreak of typhus. Mary

responded to these needs by helping locally and fund raising internationally... To

raise funds, she returned to America in 1909 where she gave speeches about famine in

Turkey, and assisted newly arrived Armenian immigrants on Ellis Island in New York.

What are we being told? Even before the war

began, conditions were so grim, the missionary herself became a victim of disease

— which was not as serious a problem as it would be during the war years. Famine

was the true culprit, however, during this pre-war stage. (Pre-WWI, that is; the

Ottoman Empire had its hands full with three other wars during this period, two in

the Balkans and one with Italy.) Both of these killers would become exacerbated as

WWI began; in the case of famine, because few men were left to till the fields after

mobilization. The British naval blockade was so successful, people began to drop

like flies from hunger, without discrimination. The disease tolls, likewise, hit the

Ottoman Empire worse than the other nations involved in the conflict. Yet, when the

Armenians died of these conditions that affected everyone, they became victims of

"genocide."

A comparison of soldiers who died of disease

— American: 60,800. British: 108,000; French: 179,000; German: 166,000; Russian:

395,000. None suffered more than the Turks; General Harbord believed 600,000 were

killed from typhus alone; about half of the 2.5 million man army was admitted to

often inadequate hospitals and infirmaries. Deaths from disease exceeded battle

losses. And these are the results for the soldiers, the difference between life and

death for the nation. Civilians, who were treated with less priority, were a

different story.

Fighting had erupted 200 miles

away on the Russian Front and a typhus epidemic was raging in the town of Erzerum.

The Sivas mission offered to send a Red Cross unit to assist in caring for the sick

and wounded until reinforcements arrived from greater distances. Thus, Graffam left

Sivas for Erzerum with a small party consisting of the mission's doctor, two nurses,

and a pharmacist, to volunteer as a nurse for a Red Crescent Hospital on the frozen

Russian Front. "I did not go to help the Turks particularly," she recalled

in 1919, "I went to work with the Turks, thinking that possibly I could get on

the good side of some of the pashas, and it might help us later on, for I felt the

time was coming when we would need such help."

What kind of a "Christian" was Mary

Graffam, anyway? Here are these poor Turkish soldiers (of whom even her ABCFM

colleague Dr. Clarence Ussher reported: "the Turkish soldier...was not

protected from heat and cold, nor from sickness") who had nothing to do

with the diabolical "genocide" plans that Graffam was a

"witness" to, and she only decided to help the Turks to get leverage for

the people who really counted in her good book, the Christian Armenians. This is a

typical attitude of the false Christian missionaries; the Muslims simply did not

rate as equal human beings, in contrast to the teachings of Jesus:

"There is neither Jew nor Greek, there

is neither slave nor free, there is neither male nor female; for you are all one in

Christ Jesus." (Gal 3.28)

"Turkish officers

apparently never forgot Graffam's hospital services during this early phase of the

war. They continued to send her letters of appreciation until the time of her death,

she received the decoration of the Red Crescent by Imperial Grade from the Turkish

government in 1917, and it appears likely that Turkish officers extended practical

favors to her during the remainder of the war that helped her to accomplish more

difficult and subversive missions that still lay ahead."

Billington Harper continues: "Early in 1915, after the military campaign had subsided, she

and one of the nurses, Marie Zenger, started back to Sivas. The inns were full of

soldiers dying of typhus and the roads were lined with dead and dying men and

horses." Doesn't that sound familiar to the bodies found on roads we

hear of in genocide accounts? The implication is that these were all Armenians, and

were "murdered." Yet, as early as 1915, we can see indications that the

Ottoman Empire was a graveyard. As conditions deteriorated and the situation became

more desperate later in the year, you can bet even more people died of famine and

disease. The ones accounted for here are soldiers, but famine and disease spared no

one. Billington Harper documents (p. 223): "Typhus was

rampant throughout north-eastern Turkey and sick and hungry deportees had begun to

arrive from the Black Sea coast." The question needs to be asked: of the

ones who died, what killed these "deportees"? (Let's keep in mind the

Ottoman government also "deported" some of its Muslim citizens out of the

"war zone" and these Ottomans "deported" themselves when the

Russians and Armenians invaded and acted in inhumane manner... to say nothing of the

Muslims who were truly "deported" forever from their lands in Russia, and

— among those who weren't slaughtered — later from Armenia.) Not to say there

weren't Armenians who couldn't keep up with the caravans and met a fatal end —

unfortunately, it was "1915" and it was the bankrupt, resource-challenged

"Sick Man of Europe." But the big picture is: Since most of the Armenians

died of famine and disease, the same for all other Ottomans (including the

soldiers), isn't it a despicable conclusion to conclude the cause of these deaths

must have been "murder"?

We're told "Michael

Frengulian and Rupen Racubian, both degree men from American colleges... were both

marked men, and would be in constant danger . . . Both were later murdered, one in

the deportation, the other was taken out of prison, in a systematic murder scheme,

by which two [sic] men a day were taken out of jail, escorted outside the

city by police, compelled to dig trenches, knocked in the head, stripped and buried.

These men were the picked leaders of the Armenian residents." The

source: Ernest and Winona Partridge, "Mary Louise Graffam: A Missionary

Heroine," from the ABCFM Individual Biographies, p. 9 [With the helpful

Billington Harper addition to the footnote, "Other sources suggest it was 200

men per day." Why not? The more the merrier.]

I'm not saying these men did not die; I wasn't

there, and neither were you. But let's examine the "murder" charges. One

died in the "deportation" (that word means banishment outside a country's

borders. The Armenians were not moved out of the country, but around

the country. "Deportation" is the choice word, because it sounds more

handily "evil"... like when the Russians deported over 700,000 Muslims

with the clothes on their back, kicking them out of their ancient homes forever, and

when the 1992 Armenians and Russians deliberately frightened away nearly a million

Karabagh Azeris [unlike the 1915 Armenians, who were allowed to return], and of whom the hypocritical and

bigoted Western world did not shed a single tear in the former case and almost none

in the latter.) How did one of these men die in the "deportation"? We're

not told. But if he died of famine or disease like everyone else was dying, how

irresponsible and dishonest of the Partridge missionaries to use the word

"murder." As far as the details regarding how the other one was killed...

was our dishonest missionary source actually there, with a front row seat? Of course

he was not. Did he have a motive to make the Turks look as bad as possible? Of

course he did.

Did these men deserve to be among those

arrested? Miss Graham makes them out to be the finest men, brave and generous.

Perhaps they were... but chances are they weren't so innocent. College professors

from... America? The greatest mischief in this "genocide" episode was

created by foreign Armenians; imagine those connected with missionaries. The mission

schools, whether they intended on doing so or not, fostered discontentment and

subversion among the previously satisfied Armenians. The Protestant missions made

trouble for the Sultan as well as for the Armenian church. The missionaries often

thought of themselves as meddling consuls. If anything, "enlightened"

Armenians from America were not going to able to restrain themselves from especially

adding fuel to the revolutionary spirit.

|

WHAT ELSE WAS HAPPENING IN SIVAS?

"The

uprisings seen in the neighbouring provinces after the declaration of war were

equally seen in Sivas and its environs. An Armenian priest by the name of

Seponil from the village of Yayci in the district of Karahisar visited

villages on the pretext of collecting aid for the Church, gathered Armenians

and said to them"

"The Ottomans entered the war in which they will be

defeated. Russians will soon enter Erzurum, and come up to here. Russians will

beat the Army in front, we in the rear. The hour has come to use the arms that

we had distributed to you in time."

"...Large scale incidents were preventedin the region thanks to the

necessary measures taken by the government in time, yet Armenians still

committed massacres and atrocities in the region." (From Archive

Documents about the Atrocities and Genocide Inflicted Upon Turks by

Armenians.)

The Sivas governor in an internal telegram (never meant to be released

publicly, and therefore can not be construed as propaganda) wrote on April 22,

1915, two days before the Armenians' cherished "Date of Doom":

"According

to the statement of the suspects who were caught, the Armenians have armed

30,000 people in this region,15,000 of them have joined the Russian Army, and

the other 15,000 will threaten our Army from the rear..."

That's

from the mouth of an Armenian prisoner, and all of these Armenians originated

from just one region of the Ottoman Empire... putting into plan their

full-scaled rebellion.

How

did the locals handle such a threat?

"Unfortunately,

conscription of all Turkish men up to the age of 50 years old had left the

local villages practically unprotected and vulnerable to Armenian

depredations. This condition made hunting down the rebels problematic. The

greater need by far, at least in Sivas, was simply to provide for the

protection of the Muslim villagers themselves, and the local Jandarma were

hard pressed to accomplish this." ("Ordered to Die: A

History of the Ottoman Army in the First World War," Edward J. Erickson)

|

|

Dr. Hamparsum Boyajian

(Murad) |

One

of the leaders of the Sivas rebels was the notorious MURAD, a Hunchak terrorist

behind many of the rebellions of the 1890s. He had become an Ottoman

Parliamentarian, quitting in 1915 to

betray Ottoman Armies, as he directed guerilla wars from the Yildiz Mountains.

(ADDENDUM,

3-06:

It looks like there may have been two Murads, both from Sivas. Still checking

this; the one referred to here may not have been Boyaciyan.)

According

to this internal army

report, every Armenian over 13, based on confessions by Armenians,

were forced to enroll in Armenian committees as functionaries or

soldiers... in Van, Bitlis, Erzurum, Karahisar, and second most important

cities, Sivas, Kayseri, and Diyarbekir.

"We know from both

documentary evidence and statistics that inter-communal warfare between

Christians and Muslims was a major cause of death. The province of Sivas,

for example, was not in the war zone; the Russian army never reached that far.

180,000 of the Muslims of Sivas died." (Justin McCarthy.)

|

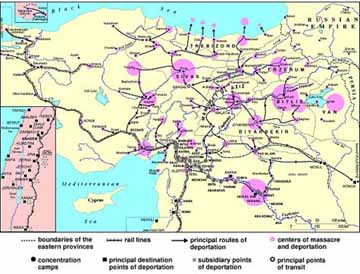

By the way: let's take a look

at the "genocide map" that this chapter's book, "America and the

Armenian Genocide of 1915" made sure to include. See where Sivas is?

Smack-dab in the middle of the

country. Now when genocide advocates ask, "how come Armenians away from the

eastern war zone were deported," you'll know the answer. (For example, see Q.

17 of Dennis Papazian's deceptive "What

Every Armenian Should Know.") The whole country was a war zone, with

treacherous Armenians lurking in every corner.

When the Armenians of Sivas

were ordered to give up their arms, Graffam remembered: A photographer in Sivas was

called to the Government House to photograph the collection of arms, but as they did

not make an impressive showing he was asked to return the next day when he noticed

that a great many pieces of Turkish ammunition had been added, and his photograph of

this last collection was used as official evidence that the Armenians were armed

against the Turks. (Miss Graffam's Own Story.)

We don't need Miss Graffam to tell us the

Armenians weren't armed. We know from many Western sources the Armenians were armed with secret caches of weapons,

uniforms, ammunition and even artillery, throughout the Empire. We know from a

Dashnak minister in Tiflis that the Russians provided a quarter-million rubles for

the initial cost of arming the Armenians. We know the

wealthy and prosperous Armenians could afford the most sophisticated guns and

rifles, such as the Mauser, which worked like machine guns. If Armenians were asked

to surrender their arms, we can be certain not everyone complied. But the specific

question to be asked here is, did Miss Graffam witness the "original" pile

of arms? Of course not. Who was in a position to view the alleged "before"

and "after" piles? Ottoman government officials. So who gave this

sensitive information to Miss Graffam... these Ottoman government officials?

Did author Susan Billington Harper even

consider the holes in this, and all the other stories? No, she did not. Why not?

|

|

153 - DISPATCHING

THE GENDARMERIE WHO ACTED INAPPROPRIATELY TO THE MILITARY COURT

[Ciphered telegram from the Ministry of the Interior to the governor of the sanjak of

Urfa, regarding court martial of the gendarmerie accompanying the convoys sent from

Urfa to Rakka, due to their inappropriate acts arising of negligence.] 28 Z. 1333 (6

November 1915)

Over a thousand Ottomans were convicted

of crimes against the life and property of Armenians during the war. At least twenty

officers were executed. More orders on the protection of Armenians may be read here.

Another set designed

to safeguard the lives of Armenians and their properties, found in the British

Archives (Sonyel, Shocking new documents, London,1975; F.O. 371/9158 E.5523) :

Article 21. Should emigrants be attacked on their journey or

in camps, the assailants will be immediately arrested, and sent to martial law court.

Article 22. Those who take bribes or gifts from the emigrants, or who rape the

women by threats or promises, or those who engage in illicit relations with them, will

immediately be removed from office, will be sent to the martial law court and will be

punished severely.

Not all these orders were followed; but

they prove the Ottomans' hearts were in the right place. As the "Witness to

Genocide" herself relates below, "Most of the

higher officials are at their wits end to stop these abuses and carry out the orders

which they have received, but this is a flood and it carries all before it."

|

"To subvert the constraints of censorship,

Graffam devised several strategies to improve communication with the outside world. First,

she utilized a code that would be recognizable to other members of her missionary

community but not to the censors."

Billington Harper spends several pages attempting to

make sense of these cryptic messages, when the meaning for most was open to

interpretation. Not that one needs to analyze these messages to see what was on Graffam's

mind, as she also had opportunity to send messages that were not censored (through

consular and diplomatic channels), and after the war, she let it all hang out in her

dictated "Miss Graffam's Own Story."

"The larger story of Graffam's

role as a valuable source of information to the American government, and of America's

response to her reports and to the reports of other missionaries, lies outside the scope

of this particular investigation," the author tells us,

adding in the footnote: "It remains an open question as to

whether Graffam was operating as an intelligence officer for the United States during the

war years. I was unable to unravel this issue, but further research may do so."

As the "deportations" began, Graffam

reported:

"Three times they came to us and

took away our men. Finally I became desperate and I decided to visit the prison, if

possible. I went to the Chief of Police (one of the ringleaders) and I was permitted to

visit the men, and this I did several times after that. This went for several weeks and

when all the men of importance were in prison, then the Vali called two or three of the

remaining men and the Armenian bishop, saying that on the following Monday (this was

Friday) the deportations would begin. The men were to go by one road and their families by

another. I was at the bank when I heard the news and went at once to the Vali, commander,

etc., trying to do something and was told that the Armenians were going to the Euphrates

valley, that was all."

While it was Billington Harper's intention to

highlight whatever bits of inhumanity, these accounts are interesting in how they deviate

from the usual Armenian propaganda. We're often told the men were all rounded up and

killed. Graffam also gives us the same conclusion, ultimately, but we can see it was not

an instantaneous process. Not only was there a "several weeks" of prison time

(why? If the idea was to kill them), but more importantly, Graffam was permitted to visit

these men on a somewhat regular basis. If the idea was to kill these men off, the

resource-challenged state would have had no reason to keep these men alive (by even

feeding them), and they surely would not have wanted a potential "witness to

genocide" to get the idea of what should have been terrible treatment. The Gestapo

surely did not permit foreign observers to visit the people that were taken away, no

matter how fluent the foreigner might have been in the German language:

"When arrest and deportation

orders were issued in Sivas, Graffam rushed to the Chief of Police and used her fluent

Turkish to persuade him to let her visit arrested Armenian men in prison. She then tried

unsuccessfully to persuade the Sivas Vali, Mora Bey, to release the men and to abandon

deportation orders. When these efforts failed, she simply announced to the Vali that she

would accompany the Armenians on the deportation, to see if they would really be as safely

cared for as he had claimed. "The Vali was very much surprised, but said

nothing," she wrote afterwards. Taking this as his consent, she began frantically to

prepare for departure with her students and teachers."

This is the most remarkable, genocide-busting

revelation in all of "Miss Graffam's Own Story." If the idea was to purposefully

exterminate these Armenians, it is inconceivable that a hostile foreign agent would have

been permitted to tag along... simply out of the realm of possibility.

"Graffam was allowed to proceed on a

deportation with 3,000 of her Armenian friends and college colleagues for five days, going

as far as the town of Malatia... She recalled: 'It was as a special favor to the Sivas

people who had not done anything revolutionary, that the Vali announced that the men who

were not yet in prison should go with their families.' ... During the next five days,

Graffam observed and partly experienced all the early stages of genocide: robberies,

deprivations of water and food, beatings, kidnappings."

Genocide is the act of intentionally and systematically destroying

members of a group, because they belong to that group. If one desires to prove genocide,

one needs to go a lot farther than dwelling on injustices that may take place for

different reasons. "Robberies, deprivations of water and food, beatings, kidnappings

" have happened ad infinitum throughout human history without the result being

"genocide." As I'm writing this in September 2005, an awful hurricane

("Katrina") has hit New Orleans, in Louisiana. Those who were too poor holed

themselves up in a sports stadium, and complete civil disorder resulted in the days to

follow. Robberies, deprivations of water and food, beatings, kidnappings, along with rape

and murder, were all experienced.

Nobody is denying the Armenians suffered awfully during the

relocation process. What is not proven is whether the central government intended for the

things that went wrong to have gone wrong. Graffam herself didn't believe so at the time

of the occurrences, as we'll soon examine. From what she has written, it doesn't sound

like the government agents, save for the bad gendarmes (assuming her account is to be

believed... Graffam was not an impartial witness), were complicit in the goings-on. (She

appears to have "revised" her views in 1919; we know how the Armenians and their

supporters feel about revisionists.)

"As they were still near home, she

believed that gendarmes protected them and 'no special harm was done.' However, by the

second night, 'we began to see what was before us': The gendarmes would go ahead and have

long conversations with the villagers and then stand back and let them rob and trouble the

people until we all began to scream, and then they would come and drive them away."

Was this a game? It doesn't sound like these chats — assuming they

took place — were within earshot, so whatever was discussed is open to speculation. How

many of us, first of all, would choose to be a party to torment helpless people because

the police ordered us to? Naturally, Graffam and her admirer (Billington Harper) are going

to prefer perpetuating the image of Turks as grossly immoral, and thus such bad behavior

would come naturally; however, another missionary was closer to the truth when he wrote:

"...[T]he Turks are vastly superior morally to the

Europeans... the Turks are vastly more moral respecting women than Europeans... One often

hears stories of the grossest immorality of the Turks, and he hears them just as often

contradicted."

Elder Tanner, “Who Can

be So Polite and Courteous As a Turk” from History of the Turkish Mission. (The

Mormon missionaries, themselves persecuted, were sometimes not as bigoted as Protestant

and Catholic ones).

However, what makes this story especially ridiculous is that the

gendarmes would allow these sadists to have their fun, and then "come and drive them away"... what in the

world was the point?

If the idea was to deprive the Armenians of their possessions so

that they may "die quicker," why would the state "share the wealth"

among the masses? To use a Holocaust parallel, most of us are aware of how meticulously

the Nazis stockpiled everything (of the Jewish arrivals at the camps) that was of worth.

Genocide zealots eager for Holocaust parallels always remind us one murder motive of the

Ottoman government was to plunder the wealth of the Armenians. Why then would the

gendarmes... who were presumably under "genocide orders"... have allowed

criminal gangs to cart away the loot?

[The men were collected and promised return]

"but the night passed and only one man came back from those who were taken, to tell

the story of how every man was compelled to give up all his money and were taken to

prison. The next morning they collected the men who had escaped the night before."

So all the men were taken away to prison (that's code for

"massacred") and the one who got away... rejoined the "death march"?

Was he out of his mind? (Note how first we are told only one man had escaped... but in the

last sentence, the ones who escaped suddenly became pluralized.)

We get horror stories as the following: "Although

officials at Hassan Chalebe extorted 45 liras from the Sivas company — now numbering by

Graffam's estimation perhaps 2,000 people — in return for the promise of protection from

5 or 6 gendarmes, no protection materialized. 'As soon as the men left us,' Graffam

recalled: the Turkish Arabajis began to rob the women saying 'you are all going to be

thrown into the Tokma Su [River], so you might as well give your things to us and then we

will stay by you and try to protect you.' Every Turkish woman that we met said the same

thing. The worst were the gendarmes who really did more or less bad things. One of our

school girls was carried off by the Kurds twice but her companions made so much fuss that

she was brought back."

I'm not sure I follow regarding the 5 or 6 gendarmes... the caravan

already had gendarmes, the ones who " did more or less bad

things." Were these supposed to be 5 or 6 "good" gendarmes? Even if

they were "good," if they were added to the already existing "bad"

gendarmes, were the gendarmes in each camp then going to be at each others' throats?

Another oddball notion regards the "Turkish Arabajis" who

demonstrated their bad intentions by robbing the people, and terrified them into thinking

they would all be murdered. Who would believe the bandits would make good on their promise

to "protect" the women? In addition, if the bandits were given a free hand to

rob these women, why would they need to "persuade" the women to give up their

goods? What was to stop the bandits from taking whatever they wanted? The logic here is as

loopy as Hitler needing to persuade his officers to rest easy with genocidal notions by explaining, "Who, after all, remembers

the extermination of the Armenians?" (As if the omnipotent and megalomaniacal

Fuehrer needed to rationalize his actions.)

Many thousands of Sivas' Armenian men had formed

bands. Since these caravans were guarded by only a handful of sometimes unprofessional

gendarmes, why weren't these Armenian men on guard, in case the Turks tried their familiar

"massacre" tricks? This is the question a

U.S. senator raised while the mandate was being considered, comparing with how men

from the USA would have behaved against a dominating force, if the Americans' women and

children were threatened.

"One of our school girls was carried off

by the Kurds twice but her companions made so much fuss that she was brought back."

I wonder why people inclined to rape and murder would have cared about that

"fuss."

Perhaps we are being asked to believe the Kurds were thieves with

honor, which probably had some truth:

"By now, Graffam was becoming truly

exhausted in her efforts to plead with persecutors. 'I was on the run all the time from

one end of the company to the other,' she wrote. Sometimes the slightest mercies from

Turkish and Kurdish persecutors produced in her an almost pathetic gratitude and even

admiration, similar to the apologetic and sympathetic feelings sometimes developed by

hostages for their hostage-takers. Graffam wrote grudgingly of her Kurdish persecutors

shortly after she was ordered to leave the deportation that 'My hat was very big and the

Kurds always made friends with me . . . These robbing murdering Kurds are certainly the

best looking men I have seen in this country. They steal your goods but not everything.

They do not take your bread nor your stick.'"

Regardless of how good-looking these Kurds were, they were

"murdering and robbing." If they, along with the gendarmes, were so out of

control, what prevented them from victimizing Miss Graffam herself? Who would have cared

if she happened to have, as Billington Harper explains, an "obviously

privileged status as the only foreigner present"?

"...[S]he also began to witness the

magnitude of the disaster that awaited the "thousands and thousands" of

deportees camping here: When we approached the bridge of the Tokmu Su it was certainly a

fearful sight. As far as the eye could see over the plain was this slow moving line of

oxcarts. For hours not a drop of water on the road and the sun pouring down its very

hottest."

But the peculiar thing is, we are being led to believe all of these

people were marked for death. If the idea was to kill them off, what stopped the

"Nazi" Ottomans from doing so? Here, Graffam describes the basic necessities

having been denied, yet there were Armenians as far as the eyes could see.

More Kurdish action; from the episodes Graffam related, looks like

the Kurds got most of the rap:

"The Kurds working in the fields made

attacks continually ... I saw the Kurds robbing the bodies of those not yet entirely dead.

I walked or rather ran back and forth until we could see the bridge. In the midst of this

chaos, Graffam attempted to continue in her role as foreign advocate for the Armenian

exiles: The hills on each side of the bridge were white with Kurds who were throwing

stones on the Armenians who were slowly winding their way to the bridge. I ran ahead and

stood on the bridge in the midst of a crowd of Kurds until I was used up. I did not see

anyone thrown into the water, but they said and I believe that an Elmas that has done

handwork for me for years was thrown over the bridge by a Kurd. Our Bodville's wife was

riding on a horse with a baby in her arms and a Kurd took hold of her to throw her over

when another Kurd said 'She has a baby in her arms' and they let her go... The last day

before reaching the river the people were crazy for water. The Kurds would sell water to

them and if they liked the looks of any of the young girls, they would carry them off; if

they did not like them they killed them."

Got that? The pretty girls were enslaved. The rest were killed.

Logical result: Zero Armenian girls left.

|

No government involvement

|

Note how Billington Harper, our

"objective" author, relates the following; Graffam must obviously have

been mistaken in thinking the government was not to blame:

Despite increasing evidence of

Turkish government officials' complicity in the massacres occurring around her, when

Graffam was writing from Malaria on 7 August 1915, she was reluctant to accuse them

openly of murder. It is possible that she felt constrained simply by the possibility

of interception by censors. However, it is also likely (and perhaps understandable)

that she was finding it impossible to believe that a government would willingly

order the extermination of a portion of its own people. Graffam was, after all,

witnessing a disaster of unprecedented proportions. It was the first large-scale

modern genocide. In describing the Sivas Vali's decision not to allow her to

complete the journey to Ourfa with the Armenian exiles, she wrote on 7 August 1915:

"That seemed to me a very great mistake on the part of the government, for

although the horrors of the present situation among the Armenians are sufficient,

the false reports are so many, that a report of an eyewitness would have been

of value if I could have continued the whole way."

How amusing that Graffam regarded herself as an

impartial witness, helping to save face for the Ottoman government. What's more

interesting is that even she was aware of the depth of Armenian propaganda, alluding

to the many false reports.

At this early date, Graffam

still apparently believed that eyewitness reports of the deportations would benefit

the government by undermining "false reports" and she seemed almost

reluctant to draw the dire conclusions suggested by the orders from Constantinople

that forbade her to proceed to Ourfa. As she recognized the complexity of local

Turkish and Kurdish involvement in the crimes, noting that some seemed fully to

support actions against the Armenians while others were reluctant or even resistant

to the actions, she was also still hesitant to issue general condemnations against

the Turkish government. She had little way of determining the reliability of

explanations and reassurances being offered by local government officials with whom

she interacted during these desperate days. In August 1915, Graffam wrote (perhaps

with censors in mind, but perhaps also with some sincerity): "I am not in

any way criticizing the government. Most of the higher officials are at their wits

end to stop these abuses and carry out the orders which they have received, but this

is a flood and it carries all before it." From her limited perspective in

the midst of the first tragedy of this sort in history, and in response to repeated

denials of wrongdoing on the part of the many local officials with whom she spoke,

she was still at least partly willing to believe that the government was not behind

the crimes unfolding before her eyes.

"I am not in any way criticizing the

government. Most of the higher officials are at their wits end to stop these abuses

and carry out the orders which they have received, but this is a flood and it

carries all before it." Isn't that the concise description as to what

actually took place, as much as Susan Billington Harper desires to pooh-pooh it.

This was a resettlement the Turks reluctantly considered only after too many examples of Armenian rebellion

and treachery the moment

the ailing Empire entered the war in November 1914.... just as the revolutionary

leaders had planned. All the official orders had the safekeeping of the Armenians in mind. When the bankrupt country

hit hard by famine and disease at all corners needed to undertake the colossal task

of transporting hundreds of thousands, things were bound to go wrong. Particularly

in the midst of desperate wartime, with superpower enemies at every gate... a

shortage of manpower and resources, corrupt and/or revengeful locals and the chaos

of overall conditions all contributed to the tragedies that resulted. Yet, the

reality is: the majority of the Armenians survived. From a pre-war population of 1.5

million, the Armenian Patriarch reported up to 644,900 in the Empire after war's

end, and before the implementation of Sèvres. Add to this figure the hundreds of

thousands of refugees who made their way to other lands not controlled by the

Ottomans. For example, Richard Hovannisian estimated 50,000 in Iran and ten times

as many in Transcaucasia.

SOMEONE

ELSE WHO BELIEVED IN NO GOVERNMENT INVOLVEMENT AND NO GENOCIDE:

"It is unlikely that a precise order to exterminate every

single Armenian came down from the ruling Turkish triumvirate of Tallat [sic]

Bey, Minister of the Interior, Enver Pasha, Minister of War, and Djemal

Pasha, Minister of the Navy. The responsibility of these men for

collective deportation is clear; but deportation — a time-honoured

strategy in nineteenth-century Turkey — while tantamount to death for

the old, the weak and the infirm, was not genocide."

Prof. Jay Winter, Editor of the propaganda book this

chapter was a part of. From his earlier work, THE GREAT WAR, 1996, Penguin

Books, P. 148. Here is an analysis of

his earlier views.

|

Yet, Billington Harper, in her haste to make her reader

believe it was all systematically planned, gives later examples from "Miss

Graffam's Own Story" that indicate her change of heart:

For instance [she recounted in

1919] there was a very deep ravine where the Turks used to cast the people and they

were killed, but the number of people who suffered this particular form of death was

very great so that finally the ravine became very full, and I know of two women who

were thrown in after this ravine was full and they were not killed. When they

regained consciousness they had to crawl through the dead bodies to get out.

Now this is the typical example of

orally-passed Armenian horror story that goes off the deep end.... as with this one, where another missionary

related that "The Turks also took all the babies in the town and threw them

into the river until it overflowed its banks." (Or this one, where an Armenian

related that yet another missionary saw "corpses... piled high to the top of

the trees.") Remember: as proven in their prayers from the period, the

missionaries' Godly mission was to vilify the Turk. Even if some were more

pure-hearted, it must have been irresistible for them to believe just about any

fantastic account told by their beloved Christian Armenians.

How many bodies would it take to fill up a

ravine, or to cause a river to overflow? The numbers would be, for all practical

purposes, "astronomical." Where did all of these ravine bodies go? Nobody

was going to take a shovel to bury these bodies, especially if they had been left at

a ravine for such a long time. Since these mass murders occurred outside today's

borders of modern Turkey, why haven't they been excavated? Since the mortality was

"1.5 million," how insurmountable would it be (with the Armenians' deep

pockets) to dig up a few thousand of these bones? Why haven't the Armenians given it

a go these many years? The Turks performed many excavations, a sampling of the

half-million that were killed from Armenian (and some Russian) treatment. Those like

Susan Billington Harper don't care about these "less human" victims, of

course.

The Turkish Government has repeatedly

been accused of trying to “end the Armenian question by ending the

Armenians,” but the evidence of many persons who travelled through the

country shortly after the previous disturbances is, that with very rare

exceptions only able-bodied men were slain, and not the women, children, or

aged. This in itself would confirm the opinion that the measures were purely

repressive and, however severe, were taken in the interest of public safety.

Unfortunately the Turk never deigns to

explain his own case, and thus the pro-Armenians always manage to hold the

field, appalling the public by incessant reiteration and exaggeration as to

the number of victims, and apparently valuing to its full extent the wisdom of

the old Eastern proverb: give a lie twenty-four hours’ start, and it will

take a hundred years to overtake it. Later on, when the true figures become

available, only a very few inquisitive people realize the falsity of the

earlier stories.

C. F. Dixon-Johnson, The Armenians, 1916

|

Graffam also gives a "personally

witnessed" massacre account in Malatia where "You

could tell where a massacre had taken place by the migration of birds and dogs,"

that Billington Harper provides to "prove" genocide. Whether or not this

particular account was true, nobody is denying there were massacres. But as "My

Lai" demonstrated, massacres do not always lead to "genocide." Who

were behind these massacres? Were they government agents, acting under orders?

Quite possibly, they were Kurds. On her trip

home to Sivas (where her Armenian driver was "taken away

and killed because a Turk had recognized his true identity, the Partridges add"):

"There are regular

places along the road where the official records of those who were killed were kept.

Accurate records were saved and when the Kurds killed the Armenians they kept a

record, and then went to these officially designated places to collect their money

which the government had promised."

That's the closest Graffam has come to

"genocidal proof." (Of course, hearsay is not factual proof, especially if

the source is a conflicted missionary.) It must have cost the bankrupt Ottomans a

fortune to pay the Kurds, who sound to have done such a complete job of

"annihilation." (I wonder what proof the Kurds needed to present, to

confirm the people killed? For example, in the Belgian Congo [toll: 10 million

killed, many mutilated], the proof was chopped-off right hands.) It's remarkable

that Miss Graffam managed to get the skinny on this confidential information... she

must have "befriended" a lot of Kurds and Turks. Or did she simply accept

the word of her beloved Armenians?

Here is where we can pin down Graffam's

dishonesty.

The above comes from her 1919 account, Miss

Graffam's Own Story, as told to a stenographer. The information she provides is

of paramount importance... it demonstrates the government was involved. Yet for all

the opportunities she had to relay previous messages, from the censored variety to

the freely written "official reports" she released through consular and

diplomatic channels, she evidently did not reveal this critical information that she

"witnessed" all the way back in 1915. Quite the contrary, her 1915

accounts let the government off the hook. Can we imagine what a field day Morgenthau

would have had with some real genocidal proof, had the energetic missionary put her

mind to collecting the real evidence?

Perhaps the missionary was confusing the matter

with this other reward policy.

[Read Here]

Enver noted that it was undesirable to use

either regular Turkish troops or the mobile Jandarma regiments against these

rebels (these troops were then badly needed at the front). He therefore directed

that the local and permanently based (static) Jandarma battalions be used to help

capture the rebels. He also recommended that a reward system of one Turkish lira

per every captured rebel be established to encourage local inhabitants to turn in

the rebels. Edward J. Erickson, "Ordered to Die: A

History of the Ottoman Army in the First World War," 2001.

[Close]

As she became more fervent in 1919, she might

well have been thinking her Godly duty was being served by making greater

incriminating statements. (Another 1919 example being the German

who foretold the "genocide" in 1914.) Shame on her, and shame on present

day partisans who pass off these reports as "fact."

"Back in Sivas, local

government officials presented her with a cruel ultimatum: either she stay in Sivas

to care for remaining orphans in the Swiss Orphanage, or the orphans would also be

deported. Graffam opted to stay. Her sister and brother-in-law, who had since

returned to America, believed that 'the underlying motive' for this government offer

'was the unwillingness to have her come back to America, and tell the story of the

deportations as she saw them.'"

At this point in the story, it appears there is

nothing to stop Graffam and the Partridges from making up all sorts of claims. If

these brutal Turks really wanted to seal Graffam's lips, the easiest thing to

arrange in what sounds like no man's land would have been a little

"accident." (After all, it is in the nature of "The Terrible

Turk" to kill... isn't it?)

"She also obtained

permission to begin visiting Armenian men in prison condemned to death by edict

without trial. These numbered between 1,000 and 2,000 (estimates vary). Every night,

between 100 and 200 of them were taken to a spot a few miles from the city where

they were 'compelled to dig trenches, disrobe, knocked in the head, [and] thrown

into the trenches and buried.' Graffam wrote: 'I went to the prison every night to

say good-bye to them.' In the case of imprisoned Michael Frengulian, the graduate of

Oberlin College and Professor of Mathematics who had earlier rescued her on the road

from Erezrum, she shared his agonized deliberations about whether to accept his

captors' offer to save his life by converting to Islam and teaching in a government

school. Frengulian refused the offer and Graffam returned the next morning to find

an empty prison cell..."

Looks like the monstrous Turks didn't even

bother to kill these Armenians... they appear to have been knocked in the head, and

buried alive. (I wonder who "saw" these events taking place... it

certainly was not our "eyewitness to genocide.") Graffam is pulling out

the stops, here. Funny how the Turks have spotted her to be a dangerous conveyor of

genocidal information, and yet they are still kind enough to grant her a pass to

prison. And what's Michael Frengulian doing, still behind bars after all this time?

(Earlier in this chapter — not related here — the reader was given the strong

impression [via Graffam's coded messages] Mike was already a goner.)

And there's the old "forced conversion to

Islam" bugaboo rearing its ugly, propagandistic head. Even some of those