|

|

Professor Heath W. Lowry

The ISIS Press, İstanbul - Turkey, 1990

With Thanks to www.eraren.org

|

|

|

| Why

Was Ambassador Morgenthau's Story Written? |

ANY examination of the genesis of the Morgenthau

'Story,' must begin by focusing on a letter the Ambassador addressed to his friend and

confidant, United States President Woodrow Wilson, on November 26, 1917. For it is in this

previously unpublished letter that Morgenthau set forth both his idea of writing a book,

and his aims and objectives in desiring to do so. He combined his concept with an appeal

for the President's 'blessing' as it were for his proposal. Given the fact that his sole

aim was fostering public support for the United States war effort by writing a work of

anti-German, anti Turkish propaganda which would "win a victory for the war policy of

the government," he not surprisingly received it. He couched his idea to Wilson in

the following terms:

"...Greatly discouraged at the amount of outright opposition and the tremendous

indifference to the war, as well as by the lack of enthusiasm among the mass of those who

are supporting the war...

I am considering writing a book in which I would lay bare, not only Germany's permeation

of Turkey and the Balkans, but that system as it appears in every country of the world.

For in Turkey we see the evil spirit of Germany at its worst - culminating at last in the

greatest crime of all ages, the horrible massacre of helpless Armenians and Syrians. This

particular detail of the story and Germany's abettance of the same, I feel positive will

appeal to the mass of Americans in small towns and country districts as no other aspect of

the war could, and convince them of the necessity of carrying the war to a victorious

conclusion...

We must win a victory for the war policy of the government and every legitimate step or

means should be utilised to accomplish it."1

In its simplest form, this study intends to evaluate the ensuing work from the perspective

of whether or not, as written, Ambassador Morgenthau's Story exceeds or adheres to his own

criteria of utilising "every legitimate means" to reach his stated goal of

convincing the "mass of Americans" to support the war.

Within a year of the date of Morgenthau's letter to Wilson, Ambassador Morgenthau's Story,

as the work he proposed was eventually titled, had been written; serialised in monthly

installments in one of America's best-known magazines, The World's Work (circulation:

120,000);2 appeared in over a dozen of the country's largest newspapers with a combined

circulation of 2,630,256; 3 released with great fanfare as a book by Doubleday, Page &

Co.,4 and already accumulated sales of several thousand copies (by July 1st of the

following year those sales would reach 22,234 copies).5

|

|

Morgenthau

|

In short, Morgenthau's goal of contributing to

America's war effort by authoring a book which would in his words, "appeal to the

mass of Americans in small towns and country districts as no other aspect of the war

could,"6 had been attained in a manner which must have exceeded even his wildest

expectations. Indeed, no sooner had World's Work begun its installments of the book's

opening chapters in May,1918, than Morgenthau received an offer from Hollywood for the

film rights of his 'story,' an offer companied by the promise of $25,000 for said rights.

After initial excitement, and the writing of a basic film treatment,7 Morgenthau's

enthusiasm for a career in the movies cooled following receipt of a second letter from

President Wilson which expressed his disapproval in no uncertain terms. Wilson wrote:

"I appreciate your consulting me about the question whether the book shall be

translated into motion pictures, and I must frankly say that I hope you will not consent

to this... Personally I believe that we have gone quite far enough in that direction. It

is not merely a matter of taste, -I would not like in matters of this sort to trust my

taste; but it is also partly a matter of principle... There is nothing practical that we

can do for the time being in the matter of the Armenian massacres, for example, and the

attitude of the c (? Country?) toward Turkey is already

fixed. It does not need enhancement."8

Less than a year earlier it had been the approval of Wilson which Morgenthau sought prior

to beginning the book project, and, indeed, it was only when Wilson had blessed the

proposal and written: "I think your plan for a full exposition of some of the lines

of German intrigue is an excellent one and I hope you will undertake to write and publish

the book you speak of,"9 that Morgenthau responded positively to preliminary

inquiries from Burton J. Hendrick of Doubleday, Page & Company's The World's Work, 10

and the project began to materialise. It would be somewhat surprising to find the

President of the United States of America and an ex-Ambassador communicating on a topic of

this nature. But, this was wartime and, as the Morgenthau-Wilson correspondence

illustrates, from its inception, Ambassador Morgenthau's Story was conceived as an

integral part of 'President Wilson's Story' as well. It was a desire to increase support

for Wilson's war effort which prompted Morgenthau to write an anti-German, anti Turkish

work, which would convince the American public of the "necessity of carrying the war

to a victorious conclusion,"11 In other words, as envisaged by Morgenthau, his

'story' was intended as wartime propaganda, i.e., as a contribution to the Entente war

effort. It is against this background that we must attempt to examine how and by whom the

book was actually written, as well as the larger questions concerning the accuracy or lack

thereof of the 'story' it purports to tell.

FOOTNOTES

The largest public collection of papers relating to the life and career of Ambassador

Henry Morgenthau (1856-1946), is preserved in the Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

Housed in the Library's 'Manuscript Division; under the title 'The Papers of Henry

Morgenthau; they consist of approximately 30,000 items which are made available to

researchers in the form of a set of 41 reels of microfilm. In the present study references

to materials in this collection will be given in the following format: LC: PHM-Reel No.

-followed where applicable (as in the case of correspondence) by a date. In the case of

the present document, the citation is LC: PHM-Reel No. 8 - HM letter to President Woodrow

Wilson of November 26,1917.

The World's Work was a

monthly publication owned in this period by Doubleday, Page 8z Co., the New York

publishers. Beginning in its Apnl,1918 edition with an article by Burton J. Hendrick

entitled: "Ambassador Morgenthau's Story-Introductory Article,' this periodical

serialised in seven installments (which ran between May and November), the Morgenthau

book. To Professor Robert J. Rusnak of Rosary College in Illinois, I am indebted among

other things, for the circulation figures of The World's Work. Prof. Rusnak's doctoral

dissertation was devoted to a study of this journal and its impact.

The second major collection

of Morgenthau Papers is housed in the Franklin Delano Roosevelt Presidential Library in

Hyde Park, New York, as part of the collection titled: The Papers of Henry Morgenthau, Jr

;' Ambassador Morgenthau's only son who served for many years as a member of the Franklin

D. Roosevelt Cabinet. This collection, comprising some 414 linear feet, is divided into

eleven series, of which Series nos.8 and 10 contain papers relating to Ambassador

Morgenthau. Specifically Scries No. 8, the 'Gaer File; is material collected by Joseph

Gaer, Morgenthau Junior's collaborator in his unpublished autobiography. In this series we

find a typed transcript of all correspondence between Ambassador Morgenthau and his son.

Material in this series which is cited in this study, will appear as: .FDR: HMJ/Gaer-Box

No. . Series No.10 is titled the 'Papers of Henry Morgenthau, Sr.' and consists of some 10

linear feet of primarily business and personal correspondence. When cited in this study,

items from this collection will appear as: FDR: HMS-Box No.

The circulation figures for

the newspapers which published Ambassador Morgenthau's Story are found in a letter from

Frank Doubleday of Doubleday Page & Co. (Morgenthau's publisher), to Henry Morgenthau,

Sr. of October 17,1918 (FDR: HMS - Box No.12). This letter was originally accompanied by a

list of the actual papers which were running the serialised version of the book.

Unfortunately, this list is lost or separated from the letter.

Having worked in Libraries and Archives in a number of countries, I would b&127;

remiss were I not to express my thanks and appreciation to the staff of the Roosevelt

Library, who made my all too brief stay in Hyde Park a working pleasure. In particular my

research benefited from the gracious assistance provided by Ms. Susan Y. Elter, an

Audiovisual Archivist at this facility.

FDR:HMS-Box1)To.12 (Letter of October 17,1918 from Doubleday to Morgenthau) mentic Zs that

the publisher has arranged windows in Macy's, Brentano's, Wanamaker's, Scribner's, etc.,

in addition to sending out advance copies of the book and various publicity releases.

The third major collection

of materials utilised in this study, arc the personal papers of the late Burton J.

Hendrick. Hendrick, a distinguished author and journalist was the individual who actually

'ghosted' the Morgenthau book. Through a New York Times obituary (March 25, 1949), which

detailed the life and achievements of Hendrick, I was able to trace his grandson, a Hobart

Hendrick, Jr. of Hamden, Connecticut, who most graciously answered all my queries. He, in

turn, put me in touch with a cousin, Martha Rusnak of Winfield" Illinois, whose

husband, Robert Rusnak, a professor of History at Rosary College, has actually written on

his wife's grandfather. Professor Rusnak most kindly provided me copies of a number of

documents from the 'Papers of Burton J. Hendrick; which are in their collection. Those

included correspondence between Morgenthau and Hendrick, and, in particular an unpublished

Rusnak study on Hendrick, called: "'To Cast Them in the Heroic Mold': Court

Biographers - The Case of Burton Jesse Hendrick." Professor Rusnak also informed me

that Hendrick had participated in the Columbia University Oral History Project and been

interviewed by Alan Nevins shortly before his death in 1949. Material cited in this study

from the Hendrick materials supplied by Prof. Rusnak will appear as: Hendrick/Rusnnk

together with a description of the actual item being referred to.

The sales information

figures given here are found in a handwritten document in the Hendrick/Rusuak papers which

is headed: "Statement of Profit and Loss to July l,1919 on 'Ambassador Morgenthau's

Story' by Henry Morgenthau:' This document, apparently written by Morgenthau himself,

shows sales as of that date totalling 22,234 copies.

LC: PHM - Reel No. 8 : HM Letter to President Woodrow Wilson of November 26,1917.

Hendrick/Rusnak Among the

material provided by Robert Rusnak relating to the Morgenthau-Hendrick collaboration, is a

typed 8 page document titled: "Proposal for a Moving Picture on tho Near East, Based

to a Considerable Extent on Ambassador Morgenthau's Story." Across the top of this

document is the following handwritten note: "This great scheme (for which the moving

picture people o f offered us $25,000) was busted by the was suddenly coming to an end!

B.J.H."

LC: PHM - Reel Nu. 8:

President Woodrow Wilson letter to Henry Morgenthau of June 14,1918. The emphases in this

quotation and throughout this study are the present author's.

LC: PHM-Reel No. 8:

President Woodrow Wilson letter to Henry Morgcnthau of November 27,1917. Interestingly,

whereas Morgenthau's November 26,1917 letter to Wilson has never been published, he did

include the President's answer in his 1922 autobiography, All In A Life-Time. New York

(Doubleday, Page 8z Co.),1.922. p.297, and cites it as the reason he wrote his book.

FDR:HMS - Box No. 11 : Frank

Doubleday letter to Henry Morgenthau of November 7,1917; Henry Morgenthau letter to Frank

Doubleday of November 12,1917 in which Morgenthau states:

"Since Mr. Hendrick

called upon me I have again carefully considered the advisability of writing a book about

my experiences in Turkey and have now definitely concluded that this is not the time to

publish it:' However, upset by lack of public support for the war, two week later he asked

the President's blessing and following receipt of Wilson s November 27,1917 letter changed

his mind and immediately entered into serious negotiations with the publisher. See also:

Frank Doubleday letters to Henry Morgenthau of 23 November and 5 December 1917, and Arthur

Page to Henry Morgenthau letters of 8 December and 20 December 1917. By the latter date,

all contract arrangements for the book had been completed.

LC:PHM-Reel No. 8: HM Letter

to President Woodrow Wilson of November 26, 1917.

|

Whose 'Story' is it?

|

Our sources for the history of Ambassador

Morgenthau's Story, are two collections of surviving Morgenthau papers, one housed

in the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C., which is known a 2 The Papers of

Henry Morgenthau (Hereafter: LC: PHM),12 and the other, part of the Henry Morgenthau,

Jr. Papers in the Franklin Delano Roosevelt Presidential Library in Hyde Park, New

York (Hereafter: FDR: HMS).13 These two collections, which comprise literally tens

of thousands of documents, must be supplemented by a wide variety of published and

unpublished materials, the most important of which are the papers of the well-known

Pulitzer Prize winning journalist,l4 biographer and historian, Burton J. Hendrick.

14 For, not only did Ambassador Morgenthau need the approval of President Woodrow

Wilson to proceed with the plan for the book which bears his name, more importantly

he needed the skilled hand of Burton J. Hendrick, to actually write the work in

question. In point of fact, it appears that the actual concept of the book

originated in the mind of Hendrick, who first suggested it to Morgenthau in April of

1916.15 It is through an examination of several thousand letters and documents in

the above-mentioned collections that eventually the rather murky origins of the work

in question emerge. To unravel the many threads which went into Ambassador

Morgenthau's Story, we must begin by discussing the various sources upon which it

was based.

First and foremost, is a typed-transcript called 'Diary' which covers the actual

period of Morgenthau's sojourn in Istanbul (Constantinople), that is, the period

from November 27, 1913 (the date of Morgenthau's arrival in the Ottoman Capital), to

his departure from Turkey on February 1,1916,16 a period of twenty six months. From

internal evidence, in particular Morgenthau,s comments about dictating to his

secretary, a Turkish Armenian named Hagop S. Andonian,17 it appears that on a

regular basis Morgenthau related his day's experiences to Andonian, who in turn

typed them up for posterity. Though extremely detailed, in particular as regards his

contacts with the Young Turk leaders, Said Halim Pasha, Enver Pasha, and Talaat Bey,

the version of events recorded in his daily 'Diary' entries often bears little

relationship (as will subsequently be demonstrated) to the descriptions of the same

meetings and discussions narrated in Ambassador Morgenthau's Story. Despite this

problem 9 there can be no doubt ; that the key source material upon which the book

was based is the daily record preserved in the 'Diary.'

In addition to his 'Diary,' and based primarily upon it, Morgenthau was in the habit

of writing a lengthy 'round robin' type weekly letter to various members of his

family back home in the United States. 18 These letters were likewise prepared by

Hagop S. Andonian, Morgenthau's personal secretary, and indeed often, as Morgenthau

tells us in a letter of May 11,1915, actually written by him:

"I have really found it impossible to sit down and dictate a letter quietly. So

I have instructed Andonian to take my diary and copy it with some elaborations of

his own. Of course this relieves me of all responsibility for any errors."19

It was then a combination of the Morgenthau 'Diaries' and 'letters' which served as

the basic raw material out of which the work was ultimately assembled. These two

sources were supplemented in some instances by copies of actual reports received by

Morgenthau in Constantinople, or dispatched by him to Washington, D.C.20 Stated

differently, these formed the skeletal framework upon which the finished product was

to be hung.

With this background in mind we must now turn to an examination of the actual manner

in which the book was written, and to the even more complex question of by whom it

was written. In this regard, in each and every edition, the author appeared solely

as: Henry Morgenthau. And today, seventy two years after its appearance, no one has

ever suggested in print that anyone but Morgenthau authored Ambassador Morgenthau's

Story.21 Despite this fact, there are abundant clues scattered about in the

surviving Morgenthau material to provide us hints as to the identity of the work's

actual author. First and foremost, is an acknowledgment made by Morgenthau in the

'Preface' to both the book's American and British editions, where he wrote: "My

thanks are due to my friend, Mr. Burton J. Hendrick, for the invaluable assistance

he has rendered in the preparation of this book."22 This acknowledgment is, to

say the least, an understatement. For in point of fact, Ambassador Morgenthau's

Story emerged from the pen of Burton J. Hendrick, with the editorial assistance of a

large number of individuals, including Morgenthau himself. In addition, he was

assisted by his Armenian secretary Hagop S. Andonian who followed Morgenthau to the

States and lived with him throughout the period in which the book was under

preparation.

Very little is known concerning the life of Hagop S. Andonian. In numerous

appearances of his name in both the 'Diary' and 'Letters' he is generally referred

to by Morgenthau as "my secretary," though on occasion he clearly

fulfilled the role of "Dragoman," (translator) as well.23 The 'Diary'

records the fact that he was a frequent guest at the Morgenthau table, and often

accompanied the Ambassador to the movies in the evening. From a reference in

Morgenthau's family 'Letter' of July 15, 191424, it appears that Andonian was a

student at the American run Robert College around the turn of the century. A

surviving photograph of the Embassy staff taken during Morgenthau's tenure, shows

him to have been in his early thirties at that time. While nothing specific has

apparently survived to shed light on the question of why he returned to the United

States with the Morgenthaus, a 'Diary' entry for February 8, 1916 clearly

establishes that he left Turkey with the Ambassador. On that date in describing a

shipboard masquerade party en route to New York, Morgenthau records that his son

"Henry was dressed as a Greek and Andonian as a Turkish lady. "25 Among

the surviving Morgenthau correspondence is a copy of a letter addressed by the

Ambassador on January 9, 1918 to the Honorable Breckenridge Long, Third Assistant

Secretary of State, requesting that official's assistance in obtaining a deferment

from military service for his secretary, Mr. Hagop S. Andonian. This letter includes

the following paragraph:

"You probably know that with the approval of the President, I have undertaken

to write a book. Mr. Andonian is assisting me in the preparation of that work and

owing to his intimate knowledge of the east and his unusual experience, his services

to me are really indispensable".26

This passage establishes three facts of interest: a) One reason for Andonian's being

in the U.S. was to assist Morgenthau with the book; b) the actual work on the book

had begun by the beginning of January 9, 1918, and, c) by 1918 Andonian was eligible

for military service in the U.S.

There are also three short references to Andonian in Morgenthau's 1918

Diary/Appointments Calendar: 1) an entry for April 26, 1918 which reads: 'Dictated

at Yale Club to Andonian and examined galley proofs of second instalment next book;'

2) an entry for April 17, 1918 reading: 'Dictated all day to Andonian and Hendrick

and, 3) a two-word notice on September 9, 1918 which reads: 'Andonian left.'27 The

next and final references to Andonian in the Morgenthau Papers are two handwritten

letters dated December 16 1920 and December 24, 1920 28. Written from Istanbul on a

letterhead bearing the names: 'Haig, Nichan, Hagop Andonian' and listing their role

as agents for the 'Sun Insurance Company,' and as real estate brokers, Andonian

writes to inquire about the truth of rumors then circulating in the Ottoman capital

to the effect that Morgenthau is to be appointed by the U.S. President to mediate

between the Kemalist and Armenian forces. Andonian offers his services to Morgenthau

should these rumors prove true (they didn't).

To anyone familiar with Turco-Armenian history in the post war period, the question

of a possible relationship between Morgenthau's Secretary Hagop S. Andonian and,

Aram Andonian, the author of the collection of forged documents known as: The

Memoirs of Naim Bey: Turkish Official Documents Relating to the Deportations and

Massacres of Armenians, London (Hodder & Stoughton), 1920, immediately comes to

mind. Both were natives of Istanbul and shared the rather uncommon surname of 'Andonian,'

which raises the possibility that they may have indeed been related. To date, no

additional information on this question has been uncovered.

Another key figure who had significant input in the preparation of the book was

Arshag K. Schmavonian, yet another Turkish Armenian who, in 1918 was in the employ

of the State Department in Washington, D.C. as a 'special adviser,' and who had

worked as Morgenthau's interpreter in Istanbul and accompanied him in all meetings

with Turkish officials. Schmavonian's role as friend confidant and adviser to

Morgenthau both during and after his stay in Istanbul is easily traceable in the

various surviving Morgenthau Papers. Indeed, almost from the day of his arrival in

Turkey, Morgenthau relied upon Schmavonian as his eyes and ears in what must have

seemed an alien environment given the fact that Morgenthau knew neither Turkish,

French, Greek nor Armenian, the four principal languages spoken in the Ottoman

Capital. Already, in a 1914 interview given shortly after his arrival in Turkey to a

correspondent of The New York Herald, Morgenthau acknowledged his dependence on

Schmavonian in the following terms:

"It will be my duty to dive into the very heart of things surrounding me. With

the help of the Legal Adviser of the Embassy, Mr. Schmavoni, who knows the Orient so

well, I shall be able to master the task in a more or less satisfactory manner in a

few weeks."

There is hardly a page of the Morgenthau 'Diary' which does not contain reference to

Arshag K. Schmavonian. He accompanied Morgenthau on almost every official visit he

paid to members of the Young Turk Government, he sat in on Morgenthau's meetings

with American businessmen (many of whose legal affairs he handled in Turkey), he

participated in all meetings with the American missionary interests (whose legal

affairs he also handled), and, also assisted Morgenthau in the writing of his cables

to Washington, D.C. The National Archives in Washington, D.C. houses a collection of

Schmavonian Papers.31 Though the overwhelming majority of these papers deal with,

Schmavonian's representations of various American business and missionary interests,

they also preserve a few handwritten notes from Morgenthau to Schmavonian, all of

which bear the salutation: 'My dear Mr. Schmavonian.' In the Morgenthau papers there

are also a large number of letters from Arshag Schmavonian to Ambassador Morgenthau,

covering the years 1914-1921.32 All of the letters written prior to 1919 bear the

salutation: My Dear Chief.'

The extent to which Morgenthau relied upon his Armenian adviser can be partially

measured by a speech he gave when raising funds for Armenian and Syrian Relief

following his return to the United States. Of Schmavonian, he wrote:

"The first man I found in the Embassy whom I could lean upon for all kinds of

assistance, the man who has done the yeoman work of the American Embassy, is an

Armenian [Schmavonian]. He has been connected with our Embassy for sixteen years. I

found him to be an unusual man, held in high regard by the Turkish authorities. My

private secretary [Andonian] was also an Armenian.

Through these two men I became acquainted with some Armenian priests and with

patriots and professors, and learned not only to respect but to love and admire many

of the Armenians."33

Nor did this relationship end with Morgenthau's departure from Turkey. The two men

were reunited in 1917 when Morgenthau was sent by President Wilson to Europe, and

Schmavonian joined him once again in the role of interpreter. Then, following the

rupture of relations between Turkey and the United States, Mr. Schmavonian was

transferred late in 1917 to Washington, D.C. where he remained in the capacity of a

'Special Adviser' until his death in January, 1922. Morgenthau wrote a moving

tribute to his memory, which illustrates the closeness of their relationship:

'Great was my pleasure to find upon meeting Mr. Schmavonian that the enthusiastic

praise of my predecessors [Ambassadors Straus and Rockhill] was not only fully

justified, but had failed to do him adequate justice. He had all the traditions of

the office most methodically stored away in his mind, and made them accessible to me

at any time, day or night, at a moment's notice, and it was the same as to all the

American missionary and educational activities in Turkey. He was so eminently just,

and so absolutely truthful, that every one with whom he came in contact, promptly

recognised the sterling qualities, and soon learned to love their possessor.

'He was a delightful social companion and graced any assembly which he attended. The

services which he rendered to the United States government and to all the

Ambassadors at Constantinople, to the missionary interests, American business

interests, and the Armenian and Jewish populations in Turkey, were unexcelled by

anyone.

'He was unobtrusive to a fault, and never claimed any credit for himself. His

devotion to his mother and to the service possessed him completely, and he was

always thoroughly loyal to his own people, the Armenians.

'The United States has lost one of its most faithful servants, and I, one of my

dearest friends.'34

Some idea of the extent of Schmavonian's role in shaping Ambassador Morgenthau's

Story may be had by an examination of his surviving correspondence with Morgenthau

during the period in which the book was written:

a) January 16, 1918 letter from Schmavonian to Morgenthau responding to an earlier

request for the names and titles of various Ottoman Cabinet members during

Morgenthau's tenure 35

b) January 26, 1918 letter from Morgenthau to Schmavonian asking him to supply facts

based on the cables and dispatches which Morgenthau sent the Department of State

from Turkey. 36

c) An enclosure of August 29, 1918 of comments on Morgenthau's manuscript prepared

by the State Department, appears to have been written by Schmavonian as well, thus

raising the possibility that he was (as might logically be expected) the official in

the Department assigned to comment on the draft of Morgenthau's book. 37

d) September 3, 1918 Morgenthau to Schmavonian letter, clearly establishes that it

was Schmavonian who was commenting on Morgenthau's manuscript. When Morgenthau

writes:

'I am sending by this mail our article No. 7, the first half of the Armenian

story... I do hope that in your good natured and accommodating way, you will work

over time, and I will promise you that I shall not write more books that have to get

the approval of the State Departanent.' 38

In short, Schmavonian was a key aide to Morgenthau both throughout his tenure in

Turkey, as well as during the months in which Ambassador Morgenthau's Story was

being written in 1918. He was even entrusted by the State Department with the task

of approving Morgenthau's manuscript. .

Despite his role at each and every stage of the project, he is not mentioned by name

in Ambassador Morgenthau's Story, an oversight which is hard to comprehend. This is

particularly so in light of the fact that he is named in Morgenthau's 1922

autobiography: All in A Life Time. In this book, which Morgenthau wrote in

collaboration with French Strother, Scnmavonian appears (as he in reality was) a

close confidant of Morgenthau.39 Can it be that Morgenthau felt that reference to

his dependence upon his Armenian assistants (Andonian is not mentioned either) might

appear strange in a book devoted partially to the Armenian Question?

Yet another participant in the project was 'the U.S. Secretary of State, Robert

Lansing who (at the President s behest?) read and commented upon every chapter of

the work in progress. The nature of Lansing's role will be discussed below; however,

a number of letters, dating from the gestation period of the book fully illustrate

that it was not insignificant:

a) Lansing to Morgenthau letter of April 2, 1918, in which the Secretary states:

"I am returning herewith the first installment of the proof of your book which

I have read with particular interest... I have made various marginal notes

suggesting certain alterations or omissions in the text before publication and I

trust that you will agree with these suggestions".

b) Lansing to Morgenthau letter of April 27, 1918, accompanying another segment of

the draft manuscript "accompanied by a few suggestions which after careful

consideration we venture to propose."

c) Lansing to Morgenthau letter of August 29, 1918, together with proof sheets and

more suggestions;

d) Lansing to Morgenthau letter of September 17, 1918 with "suggestions and

remarks,"

e) Morgenthau to Lansing letter of September 22, 1918 asking permission to

acknowledge in the Preface to the published book, his appreciation for the

"trouble taken by the Secretary of State Robert Lansing in reading the

manuscript and of the many valuable wise suggestions he has made;"

f) Lansing to Morgenthau letter of October 2, 1918 declining Morgenthau's wish to

acknowledge his assistance with the book on the grounds "that on the whole it

would be advisable not to mention my name in connection with the book."40

When one recollects the fact that prior to beginning his project, Morgenthau

received the written blessings of the President of the United States, Woodrow

Wilson, and, that as the work progressed, each chapter received the personal stamp

of approval of the U.S. Secretary of State Robert Lansing, it is clear that

Morgenthau's book may be said to bear the imprimatur of the United States

Government.

This said, what literary merit the work has, and all its reviewers found it very

readable indeed, is purely the result of Hendrick. While Hendrick was never accorded

his due in terms of open recognition of his role in 'ghosting' the story, he was

well paid for his efforts, as a surviving letter from Morgenthau to him dated July

5, 1918 attests. In lieu of a formal written contract, which does not appear to have

existed between the two men, Morgenthau wrote the following to Hendrick:

I desire to put in writing that I intend to transfer to you a share of the income of

the book, 'Ambassador Morgenthau's Story,' about to be published by Doubleday, Page

& Company.

'The definite arrangement is to be made when your work on the book is completed, but

if anything should happen to me in the meantime, I hereby direct my Executors to

arrange that you are to receive two-fifths of any profits that are coming to me from

Doubleday, Page & Company, until you have received Ten Thousand [$10,000)

Dollars, and that the first five thousand ($5,000) Dollars coming to me are to paid

to you on account.'41

Hendrick, an individual fully deserving of serious scholarly study in his own right,

must have been fully satisfied with the final 'arrangement' made at the completion

of the book. From a receipt which has survived in the Morgenthau papers we may

surmise that whatever the final agreement was, it guaranteed Hendrick's 40% share

throughout the life-time of the book. It shows that in the period between January

2,1932 and July l,1932, that is, fourteen years after its initial publication,

Ambassador Morgenthau's Story was still in print. In this six month span it

registered a grand total of $2.00 in sales, of which the author's one-half share,

i.e., $1.00, was divided as follows:

Mr. Burton J. Hendrick's 40% share . . . . . 40

Mr. Henry Morgenthau's 60% share . . . . . 60 42 Thus fourteen years after its

initial publication, the American edition of the book was still providing income to

Hendrick and Morgenthau. As for Hendrick's feelings, they were recorded in an Oral

History interview he gave the historian Alan Nevins at Columbia University, a few

months before his death in 1949. He stated:

"I had one job of 'ghosting.' That was the elder Henry Morgenthau's

Reminiscences. That book created quite a good deal of interest. I worked with Henry

all the time.

He was an interesting character. Henry Morgenthau was a very capable person, very

chummy and good natured and was a very successful man. He, of course, made a great

fortune here in New York in real estate...The writing of my books on Sims and

Morgenthau was very interesting - more or less of a job..."

Hendrick44 who within ten years of the publication of the Morgenthau book was to

receive three Pulitzer Prizes, one for the book he co-authored with Admiral William

S. Sims: The Victory at Sea (recipient of the Pulitzer Prize in History in 1920),

and two in Biography for his 1922 work, the Life and Letters of Walter H. Page and

in 1928 for his second Page volume entitled The Training of an American, was already

in 1918 a well-known journalist who had done stints as an editorial writer with The

New York Evening Post, McClure's Magazine, and The World's Work. In these positions,

in the words of his New York Times obituary writer, Hendrick "developed a

reputation for painstaking accuracy,' honest thinking and good humor and developed

an appetite for research in subjects of great historical interest." The Times

obituary goes on to say that "critics of his biographies and histories almost

invariably would remark that his freshness and penetrating analysis bore the mark of

his early journalistic training." 45

Ironically, at least one reviewer of Ambassador Morgenthau's Story, a 'W.K.K.'

writing in December 5, 1918 issue of the Detroit Michigan News, instinctively sensed

that Morgenthau must have had a journalistic collaborator when he wrote:

"...Henry Morgenthau, our Ambassador to Turkey in the first year of the war, is

either a born journalist, or else he had journalistic help in the preparation of his

volume; for 'Ambassador Morgenthau's Story' is pure journalese.."46

What we are faced with is less the memoirs of one individual, Ambassador Henry

Morgenthau, than a memoir by committee as it were. Morgenthau's Istanbul notes

(consisting of his 'Diary' and Family 'Letters'), are reworked initially by

Morgenthau and Andonian, together with Hendrick; edited for content by Schmavonian

(on behalf of the State Department); then fine tuned' by the Secretary of State

Robert Lansing (on behalf of the Executive); and, finally written down as Ambassador

Morgenthau's Story by Burton J. Hendrick.

As to the question of whose story it really is, as our subsequent examination will

illustrate, it is a collective story bearing only a cursory relationship to what was

actually experienced by Henry Morgenthau during his tenure in Turkey.

FOOTNOTES

See: Footnote #1 above.

See: Footnote #3 above

See: Footnote #5 above

FDR: HMS - Box No. 9: Burton J. Hendrick letter to Henry Morgenthau of April 7,

1916, in which Hendrick refers to discussions with Morgenthau of the possibility of

Doubleday, Page 8z Co. publishing a book which would appear in a series of

"personal narratives of all the big people who have figured in this war."

This is apparently the earliest surviving document which specifically relates to the

book project.

LC: PHM-Reel No. 5 (Containers 3£ 4):

Contain the only known ropy of this daily record of Morgenthau's sojourn in Turkey.

Simply labelled as the 'Diary; this document provides a day by day account of

Morgenthau's activities while in Constantinople. When cited in the present study, I

have listed the following information: LC: PHM-Reel No.5: 'Diary' date:. All

references in the text to 'Diary' refer to this key source of information on

Morgenthau's day by day contemporary record of his activities.

References of this nature include the following: LC: PHM - Reel No. 5: 'Diary'

entries for September 25,1914, February 19,1915. The July 8,1915 entry reads:

"We worked at the book from 7:15 to 8. Then Schmavonian and Writhe took supper

with n. " This passage raises two possibilities: a) that others than Andonian

may have also had a hand m compiling the 'Diary' and, b) that Morgenthau's 'Diary'

may have all along been envisaged as the outline for a book he intended to publish.

Given the fact that he does not appear to have ever kept such a detailed 'Diary' at

any other stage of his life, this interpretation may well be true.

Copies of Morgenthau letters arc found primarily in two separate sections (series)

of the FDR Library - Morgenthau Papers. Specifically, they are in the FDR: HMS/Boxes

5, 7, 8,10 and in the FDR: I-IMJ/Gaer- Boxes Nos. I-2. While clearly based on the

'Diary' entries for the period they describe, there is often additional data found

in the 'Letters' in that they provide a useful supplement to the sometimes laconic

'Diary' entries.

FDR: HMS-Box 7: HM to children letter of

May 11,1915. That this comment does not relate solely to the May ll,1915 letter is

confirmed by FDR: HMJ/Gaer- Box 1-2: HM letter to Henry Morgenthau, Jr. of September

l,1915, where we read: "I am sending you one of the copies of the general

letter which recently has been written by Andonian, so don't blame me if it is too

impersonal and skeletonish:' On another occasion we find the following in a letter:

"1 don't know whether you folks all noticed the difference in style between

this letter and the preceding ones. I have dictated this one myself and filled the

mere skeleton notes that I gave Andonian and from which the recent letters were

written:' (FDR: HMS - Box No. 8: Letter of 7/13/1915 - p.l5)

Copies and 'paraphrases' and Morgenthau's cable traffic are found scattered

throughout the LC: PHM-See, in particular, Reels No. 5, 7, 8,17. This material was

compared with copies of Morgenthau's official reports preserved in the National

Archives in Washington, D.C. In particular: Record Group 59 - General Records of the

Department of State: Decimal File 867.4106 - Race Problems (Microfilm Publication

353: Reels 43-48).

Henry Morgenthau, Ambassador

Morgenthau's Story. New York (Doubleday, Page & Co.),1918. (hereafter: AMS).

AMS: p. vii.

LC: HMS - Reel No. 5 for March

15-16,1915, where Andonian accompanied Morgenthau to the Dardanelles in that

capacity.

FDR: HMS - Box No. 5.

LC: PHM-Reel No5.

LC: PHM - Reel No.:8

LC: PHM - Reel No.6.

FDR: HMS - Box No.13.

LC: PHM-Reel No. 37-date is illegible.

LC: PHM-Reel No.5.

National Archives: Record Group No.

84-Personal Correspondence of Arshag K. Schmavonian - 4 Boxes.

FDR: HMS -Boxes No. 5 (17letters from

1914), 9 (4 letters from 1916),10 (2 letters from 1916),12 (3 letters from 1919),14

(5 letters from 1921).

LC: PHM - Reel No. 22.

LC:PHM-Reel No.40

LC:PHM-Reel No.8

FDR:HMS-Box No.12.

FDR:HMS-Box No.12.

FDR:HMS-Box No.12

Henry Morgenthau (in collaboration with

French Strother), All In A Life Time, New York (Doubleday, Page & Co.),1922.

See: pp.178,187, 215, 216, 224, 227, 259, and 266.

FDR: HMS - Box No.l2.

Hendrick/Rusnnk: Morgenthau to Hendrick

letter of July 5,1918.

LC: PHM-Reel No.l7.

I am indebted to Mr. Ronald J. Grele,

Director of the 'Oral History Research Office' at Colombia University's Butler

Library, for a copy of the 62 page Nevins interview entitled: 'The Reminiscences of

Burton J. Flendrick.' The passage quoted above is taken from pages 31-32 of this

interview, and is a summary of Hendrick's comments. In addition to the Hendrick

materials discussed earlier in what I have termed the Hendrick/Rusnak Collection,

and the Nevins interview, there are also 75 Hendrick letters in the archives of the

American Academy of Arts and Letters in New York City. I am informed by Ms. Nancy

Johnson, the 'AAAL' Librarian, that this material consists primarily of letters

relating to Hendrick's membership in the 'AAAL; an organisation to which he was

elected in 1923, and of which he remained a member until his death in 1949.

The most detailed work on Hendrick's

career is Robert Rusnak's unpublished paper entitled: "To Cast Them in the

Heroic Mold": Court Biographers - The Case of Burton J. Hendrick." I am

indebted to the author for a copy of this study. Additional biographical information

has been consulted in the following reference" works: a Obituary notice.

'Burton Hendrick, Historian, 78, Dies, The New York Times, Friday, March 25,1949.

p.23. (Hereafter: Hendrick, Times: p.23.) b) Burton Jesse Hendrick entry in: The

National Cyclopaedia of American Biography. Vol. XXXVIII., page 476. Ann Arbor, MI

(University Microfilms),1967. c) Louis Filler, "Burton Jesse Hendrick,"

entry in The Encyclopedia Americana (International Edition). Vol.14, page 91.

Danbury, CT (Grolier Inc.) ND. d) Burton Jesse Hendrick entry in the 1922-1923 Who's

Who in America. Vol.12, page 1482. Chicago (A.N. Marquis & Co.),1923.

Hendrick, Times: p.23.

LC: PHM - Reel No. 40.

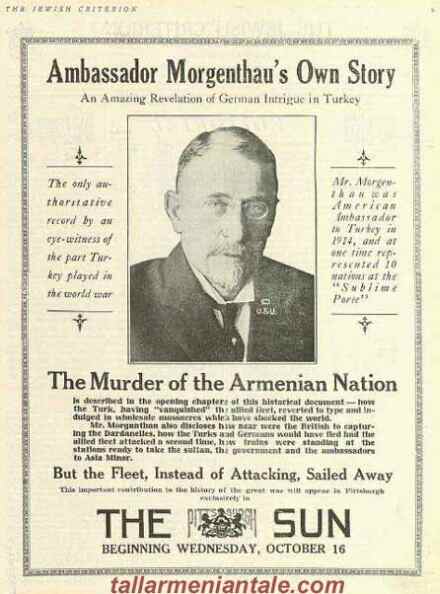

Advertisement appearing in The Jewish Criterion,

Oct. 11, 1918; "The only authoritative record of an eye-witness

of the part Turkey played in the war...The Murder of the Armenian Nation is

described in the opening chapters of this historical document -- how the Turk,

having 'vanquished' the Allied fleet, reverted to type

and indulged in wholesale massacres which have shocked the world." Morgenthau's

work is then described as an "important contribution to the history of the great war..." (Thanks to Gokalp.)

|

| The

Intent and Scope of the 'Story' |

The key questions with which the remainder of this study is

concerned are these: how much of Ambassador Morgenthau's Story which doesn't originate

from the 'Diary' or 'Letters' comes from the fertile journalistic imagination of Burton J.

Hendrick, and how much of it was invented by Morgenthau in support of his aim of writing a

sensational book damning the Turks and Germans and thereby stirring up support for the war

among his fellow Americans? In the same vein, what was the nature of the input from U.S.

Secretary of State Robert Lansing? That is, did he confine himself to censoring

potentially embarrassing diplomatic disclosures on the part of Morgenthau, or did he take

an active role in attempting to blacken the reputations of Turks and Germans alike in

keeping with his Presidential employer's and the author's stated aims? Were Morgenthau's

views of the disputes between Turks and Armenians shaped by his Armenian eyes and ears,

namely Arshag K. Schmavonian and Hagop S. Andonian?

Most importantly, what were Morgenthau's real views of the Turkish leaders and German

diplomats he dealt with during his tenure in Constantinople and how (and to the extent

possible why) had these views been altered some two years later when Ambassador

Morgenthau's Story was written?

For the benefit of those unfamiliar with Morgenthau's book, it may be necessary to set

forth its basic themes, which are four in number, in summary form:1) German ·

imperialistic motives led the naive Young Turk Government into the war; 2) The Young Turk

leadership, in particular Talaat Bey and Enver Pasha, decided to use the cover of the war

to once and for all 'Turkify' the Ottoman Empire. To aid this objective they conceived and

perpetrated a plot to exterminate the Ottoman Armenian population, whom they falsely

accused of aiding and abetting their Russian enemy in wartime; 3) Henry Morgenthau was a

lone voice tirelessly attempting to dissuade the evil Talaat and Enver from their

nefarious scheme of destroying the Armenians; and, 4) Morgenthau's efforts failed for the

sole reason that the one man who could have persuaded the Turks to alter their action, the

German Ambassador Baron Wangenheim, sat idly by and refused to speak on behalf of the

helpless Armenians.

Morgenthau's themes are given credibility by virtue of the fact that throughout his

'Story,' literally from beginning to end, his troika of villains, Wangenheim, Talaat and

Enver, repeatedly condemn themselves with their own voices of his charges, i.e., over and

over Morgenthau provides us first-person accounts, complete with quotation marks, of

comments allegedly made by these individuals which buttress his contentions as to their

roles. Indeed, the only crime that they did not openly confess to, if Morgenthau's account

is accepted, was that of 'genocide,' and that only because the term had not yet been

coined.

The question we must ask is, did these alleged conversations actually occur in the manner

described by Morgenthau/Hendrick? To answer this query we must compare a series of

statements in the book with the parallel accounts provided in the 'Diary,' 'letters,' and

reports submitted by Morgenthau to the Secretary of State Lansing in Washington, D.C.

At the outset, one fact is indisputable: None of the statements given in quotation marks

throughout the book, and purporting to be comments made by one or another Turkish or

German official, are based on written records. There simply are no such statements'

recorded in any of the sources used in writing Ambassador Morgenthau's Story. Stated

differently, the use of such quoted statements is simply a literary convention adopted by

Hendrick in telling Morgenthau's 'Story.' Their purpose can only have been to make the

words put into the mouths of the various players more believable. While this does not de

facto establish that they were false, it does mean that we should subject them to far

greater scrutiny than they have hitherto received.

|

The

Treatment of Talat Bey: a Case Study

|

The principal villain of Ambassador

Morgenthau's Story, and the subject of its greater invective, is Talaat Bey, the

Ottoman Minister of Interior. An examination of the treatment accorded him,

therefore, will serve to establish the inexplicably wide discrepancies between

events as recorded by Morgenthau in his 'Diary' and 'letters,' that is, during his

actual sojourn in Constantinople (November, 1913 - January,1916), and in his 1918

book. While in no way comprehensive, the following examples, presented in the order

in which they appear in Ambassador Morgenthau's Story, will serve to illustrate this

point:

1) In describing "Talaat, the leading man in this band of usurpers,"

Morgenthau states:

"I can personally testify that he cared nothing for Mohammedanism for, like

most of the leaders of his party, he scoffed at all religions. 'I hate all priests,

rabbis. and hodjas,' he once told me."44

In point of fact, there is not a single reference in any of Morgenthau's

contemporary Constantinople papers to support this statement. To the contrary, the

sole reference to Talaat's religious attitudes is found in a 'Diary' entry for July

10, 1914, where, in describing a small supper party he gave on the previous evening

for Talaat Grand Rabbi Nahoum and his wife, and Schmavonian, Morgenthau recorded:

"Talaat told me the other evening that he was the most religious in cabinet;

and that Djavit had none and Djemal little." 49

Even were it not known that Talaat Bey was indeed the most religious of the Young

Turk leadership

Morgenthau's own Diary' and 'Letters' contain literally dozens of references to the

close relationship which existed between Talaat and the Grand Rabbi Haim Nahoum,

leader of the Ottoman Jewish communities which make the quote attributed to him in

which he allegedly stated to Morgenthau his "hate (of) all Priests Rabbis, and

Hodjas," extremely unlikely.50

Why then did Morgenthau choose to portray Talaat Bey as an atheist, when his own

'Diary' gives the lie to his contention? The obvious answer is that he felt it would

be useful in generating the desired disgust and revulsion on the part of his

intended audience to portray the villain of the piece as a godless atheist rather

than as a supporter of religion, even if it were Islam.

2) In a section of his work dealing with the forced return of Greek settlers on the

Aegean coast of Anatolia to the islands from which they originated (in late spring

and early summer 1914), Morgenthau writes:

"By this time I knew Talaat well; I saw him nearly every day, and he used to

discuss practically every phase of international relations with me. I objected to

his treatment of the Greeks; I told him that it would make the worst possible

impression abroad and that it affected American interests."51

Contrary to Morgenthau's claim of almost daily intimacy with Talaat Bey, a thorough

analysis of his 'Diary' entries for the period between January l ,1914 and July

2,1914, establishes that Morgenthau and Talaat met on a total of only twenty

occasions, of which only eight were actual substantive meetings, the remainder being

social events where they happened to be guests at the same dinner parties.52

Throughout the period in question, Morgenthau saw Talaat for substantive purposes an

average of only once every three weeks. Indeed, during the height of the expulsions

(Mid-May - June 1914) Talaat and Morgenthau did not meet at all. Morgenthau's

'Diary' records meetings only on May 4th and again on July 2, 1914.53

Nor does the 'Diary' record a single instance, despite Morgenthau's assertion, in

which the Ambassador remonstrated with Talaat Bey over his treatment of the Greeks.

To the contrary, it establishes that the matter was the subject of discussion in

only one of their meetings, that of July 2,1914, an occasion on which Morgenthau

simply recorded Talaat's reasoning for relocating the Greeks without any indication

that he objected to it in any manner whatsoever:

"Schmavonian and I called on Talaat. He was very determined to have Greeks of

the country, not cities, leave their country he said the, Greeks here pay taxes to

Greece Government collected by Metropolitan; he says they want their islands back

admitted Greek superiority in education and mercantile capacities..."54

In the weekly letter to his family of July 15, 1914, he records the same

conversation as follows:

"In the afternoon, I paid a visit on Talaat. He was extremely frank... They are

unquestionably determined to have such Greeks as live out of their cities to part

from their country as peaceably and as soon as possible. The thing that seemed to

annoy him most was that these very Ottoman Greeks are paying taxes to the Hellenic

Government, and some of the very money that is earned on Turkish soil will be used

to pay for the ships that Greece has just purchased from us. My secretary [Hagop S.

Andonian] just informs me that when he attended Robert College twelve years ago, the

Greek students used to pay every week something from their pocket money as a

contribution to the Hellenic fleet. Talaat admitted to me that they either want the

islands back or the Greeks expelled from the mainland.' 55

Far from remonstrating with Talaat Bey over the Ottoman treatment of their Greek

population, there is not a hint in anything Morgenthau recorded to suggest that he

found their policy unacceptable. Why then in 1918 does he claim that "I

objected to his treatment of the Greeks," or that he "saw him [Talaat]

nearly every day" and "he used to discuss practically every phase of

international relations with me? 56 Once again, there can be only one reason: he is

laying the groundwork for his claim of intimacy with Talaat on one hand, and, on the

other, seeking to establish his credentials as a defender of any and all minorities

persecuted by the hands of the Moslem Turks.

3) In attempting to describe the motivations impelling Talaat's treatment of

minorities, Morgenthau writes:

"...Talaat explained his national policy; these different blocs in the Turkish

Empire, he said, had always conspired against Turkey; because of the hostility of

these native populations, Turkey had lost province after province — Greece,

Serbia, Rumania, Bulgaria, Bosnia, Herzegovina, Egypt and Tripoli. In this way the

Turkish Empire had dwindled almost to the vanishing point. If what was left of

Turkey was to survive, added Talaat, he must get rid of these alien peoples. 'Turkey

for the Turks' was now Talaat's controlling idea." 57

This alleged conversation, complete with Talaat's use of the phrase "Turkey for

the Turks," was, according to Ambassador Morgenthau's Story, part of the same

discussion referred to above in which Talaat explained his desire to force the Greek

settlers along the Aegean Coast to return to their original homes on the islands. As

we have already seen, no reference to anything supporting Talaat's alleged views on

'Turkey for the Turks' was recorded by Morgenthau in either his 'Diary' or 'Letter'

dealing with that meeting.

Why then did Morgenthau put these words into the mouth of Talaat

Bey? Again, the answer is simple: he wanted to have the strongest figure among the

Young Turk triumvirate embracing verbally what is one of the major leitmotifs of

Ambassador Morgenthau's Story, namely, it was runaway Turkish nationalism which

prompted their attempt to "exterminate" the Armenians. This theme, which

does not find a single iota of support in either the 'Diary' or the 'Letters,' runs

throughout his book. Over and over we read statements such as 'Turkey for the

Turks,' 58 'In his eyes Turkey was the land exclusively of the Turks; he despised

all the other elements in its population,'59 'It was his determination to Turkify

the whole Empire. 60 'They decided to establish a country exclusively for Turks,'61

'Their passion for Turkifying the nation seemed to demand logically the

extermination of all Christians,'62 and, 'The time had finally come to make Turkey

exclusively the country of the Turks.'63 It is almost as if we are being subjected

to some kind of 'subliminal' repetition designed to convince us that the Young Turks

were racist ideologies. If Morgenthau himself had come to believe this of the Turks

in 1918, he had certainly done so after leaving Turkey in 1915, for seemingly

nothing he recorded during his sojourn in Constantinople serves to buttress such a

view.

4) In describing a meeting with Talaat on October 29, 1914, in which the topic of

discussion was the Turkish German alliance, Morgenthau relates the following

discussion:

"At this meeting Talaat frankly told me that Turkey had decided to side with

the Germans and to sink or swim with them. He went again over the familiar grounds,

and added that if Germany won — and Talaat said that he was convinced that

Germany would win — the Kaiser would get his revenge on Turkey if Turkey had not

helped him to obtain his victory." 64

In other words, Talaat is portrayed here as an individual who has taken a real

politik decision and decided to side with Germany on the grounds that in his own

opinion she is going to win the war. While no family letter covering this meeting

has survived, Morgenthau did record his actual impressions of his October 29,1914

meeting with Talaat in his 'Diary,, presumably within hours of its occurrence. This

is what he wrote:

"Called... on Talaat... We had a most interesting talk, He admitted frankly

that they had decided to side with Germans; sink or swim with them; he said they had

to have strong country to lean on and if they had not agreed to depend on Germans,

they when defeated would have been first to suggest cutting up Turkey; they were

prepared to swim or sink with them." 65

In the book, Morgenthau has twisted his 'Diary' entry to transform a very reluctant

Talaat, one who has no opinion as to the likely outcome of the war, one who has

simply embraced the lesser of two evils in a hope to stay afloat, into a calculating

pro-German, who, having weighed the alternatives, comes down on the German side

because of a belief in German invincibility. Why? Because it hardly suits his thesis

to have his key villain not firmly committed to the evil German war machine. Once

again, Morgenthau has sacrificed any claim to historical accuracy for what can only

be termed the short-term propaganda coup.

5) In discussing a late evening visit on the night of November 3, 1914 to Talaat's

home for the purpose of protesting the treatment of English and French civilians,

Morgenthau writes:

"'Well, Talaat,' I said, realising that the time had come for plain speaking,

'don't you know how foolishly you are acting? You told me a few hours ago that you

had decided to treat the French and English decently and you asked me to publish

this news in the American and foreign press...

A piece of news which Talaat received at that moment over the wire almost ruined my

case... Talaat's face lost its geniality and became almost savage, he turned to me

and said:

"The English bombarded the Dardanelles this morning and killed two Turks.'

And then he added:

'We intend to kill three Christians for every Moslem killed!'

...Finally the train was arranged. Talaat had shown several moods in this interview;

he had been by turns sulky. good-natured, savage and complaisant.." 66

This account, which covers some six pages in the Morgenthau book, portrays Talaat

Bey as some kind of eccentric child, beguiled by the candor of Morgenthau into

eventually acceding to his every wish. A good part of it consists of alleged

conversations given as direct quotations. Much is made of Talaat Bey, who started

life as a telegraphist, "sitting there in his grey pyjamas and his red fez,

working industriously his own telegraph key, 67 etc. etc. In point of fact, the

entire source for this six page uninterrupted dialogue between Talaat and Morgenthau

is the following entry in his 'Diary' for November 3,1914:

|

|

Arshag Schmavonian |

"Schmavonian and I went to [Sublime] Porte

and then to Talaat's house, he in pajamas, wife peeping through doors. Bedri

appeared phone working. I put it strong that I had spread news all the world and if

they balked condemnation follows; he admitted it was general German Chief of Staff

who had just returned thought they were too lenient and interfered. There is already

conflict between civil and military and Germans and Turks; troubles ahead; Promised

to try and let foreigners [stay in) interior unless Beirut, Smyrna, or other

unprotected ports were bombarded, then all would be kept as hostages. Smyrna

Governor would inform our Consul that three Christians be killed for every Moslem

that was killed. Dardanelles had been bombarded from 8:30 to 8:40 and two Turks

killed At 7:45 Talaat told us train could go. We returned to station about 8:10 when

it was announced it could go. Such joy." 68

Here is an almost classic case of the account in Ambassador Morgenthau's Story

bearing almost no resemblance to the passage in the 'Diary' upon which it should

have been based. From the portrayal of Talaat "this huge Turk" hunched

over his telegraph machine and "banging the key with increasing

irritation,"69 (when in point of fact he was speaking on the telephone), to his

alleged response to the bombing of the Dardanelles which had resulted in two

civilian deaths, of promising to 'kill three Christians for every Moslem killed, 70

(combining two totally unrelated events out of sequence), that is, from start to

finish, the entire section appears to be nothing more real than the rambling of an

overactive imagination; Again, the question is why? Here too, it is Morgenthau s

intent to portray Talaat Bey, as his prototypical Turk, as bestial, crude, and

vicious in his actions. Only the cajoling influence of the American Ambassador,

Henry Morgenthau can stem the unpredictable, dangerous Turk. In reality, the

Minister of Interior, and de facto head of government of a state to which Morgenthau

was accredited as Ambassador of a foreign country, received him in a crisis

situation at home, and spent some time resolving the issue of foreigners who were

citizens of belligerent nations wishing to leave the country without exit visas, via

a series of phone calls. This act of gracious kindness is twisted into a parody of

fact in which Talaat is depicted as an emotionally unstable, petulant schoolboy who

can only be controlled by the firm-speaking Henry Morgenthau. While Burton Hendrick

could be excused if he had misunderstood the laconic entries in the 'Diary ' it

appears that all the fictional detail in this section of the book had to have been

added in 1918 by Morgenthau himself.

6) Many times it is hard to find any linkage between the passages in the book and

the 'Diary' references they are obviously supposed to be drawn from. One such

example is the following. Morgenthau et al. write:

"I called on Talaat again. The first thing he did was to open his desk and pull

out a handful of yellow cablegrams.

Why don't you give this money to us?' he said, with a grin.

What money?' I asked.

Here is a cablegram for you from America, sending you a lot of money for the

Armenians. You ought not to use it that way; give it to us Turks, we need it as

badly as they do.'

'I have not yet received any such cablegram.' I replied.

'Oh, no, but you will,' he answered. 'I always get all your cablegrams first, you

know. After I have finished reading them I send them around to you. 71

Not only does Talaat Bey read other people's mail, he brags about it. Not only does

he carry out the 'extermination' of the Armenians, he is so heartless that he

actually dares to ask Morgenthau to give him the money which generous Americans have

collected for the relief of these suffering people. It takes a careful reading of

the Morgenthau 'Diary' to find the entry that served as the source for this

statement. It reads.

"He [Talaat] asked me if I would take additional money offered by U.S. to me by

cable received today; it was an admission that he had read or knew contents of my

telegram. 72

There are several problems with the interpretation of this passage given in

Ambassador Morgenthau's Story:

a) The 'Diary' entry for its source is dated October 14, 1914, a full six months

prior to the onset of the Armenian deportations, and at least ten months prior to

the arrival of any American aid earmarked for Armenians,

b) The 'Diary' entry makes it clear that Morgenthau has already received the

telegram in question, i.e., Morgenthau does not suggest that Talaat is referring to

a message he has not already seen;

c) Morgenthau only infers from Talaat's question that he has seen, or has been

informed of a cable on the subject of funds; he is not so informed by Talaat himself

who, in the book, brags of receiving all cables prior to Morgenthau ever seeing

them.

Clearly, Hendrick, with the tacit approval of Morgenthau, has simply fabricated yet

another discussion between Talaat and Morgenthau for the purpose of portraying the

Turkish leader as a thoroughly disgusting and inhuman character.

7) On occasion, Morgenthau even goes beyond 'poetic license' and

literally records alleged conversations which, have no foundation whatsoever in

either the Diary or the 'Letters. In perhaps the most damning indictment of this

nature, Morgenthau writes:

"One day Talaat made what was perhaps the most astonishing request I had ever

heard. The 'New York Life Insurance Company' and the 'Equitable Life of New York'

had for years done considerable business among the Armenians. The extent to which

these people insured their lives was merely another indication of their thrifty

habits.

'I wish,' Talaat now said, 'That you would get the American Life Insurance Companies

to send us a complete list of Armenian policy holders. They are practically all dead

now and have left no heirs to collect the money. It of course all escheats to the

state. The Government is beneficiary now. Will you do so?

This was almost too much, and I lost my temper. 'You will get no such list from me,'

I said, and I got up and left him. 73

Perhaps more than any single incident related in Ambassador Morgenthau's Story, this

callous disregard for human life and decency etches itself into the reader's memory.

Surely, no one could have invented such a conversation. It must have occurred as

related by Morgenthau. But did it? A careful examination of everything written by

Morgenthau from the beginning of the Armenian deportations in April of 1915 to the

date of his departure, on February 1, 1916, fails to locate a single reference to

this alleged conversation. Given the fact that we have hundreds of references in the

'Diary' for this period to Talaat and to matters affecting the treatment and

mistreatment of Armenians, this lacuna is difficult to explain. Morgenthau, in

addition, filed numerous reports to the Department of State relating to Armenians,

not one of which makes any reference to this discussion. Finally, for the period in

question we have a complete run of 'Family Letters,' comprising several hundred

pages, which are literally filled with references to meeting with Talaat and

discussion of the treatment of Armenians. Their contents refer to every single day

during the last twelve months of Morgenthau's tenure in Turkey, and yet, they too,

fail to make any reference to Talaat's callous request that the Turkish Government

be recognised as the beneficiary of the insurance policies held by the very

Armenians whose lives had been lost as a result of the treatment they had been

accorded. More telling than his argument by absence' is the fact that this is the

only alleged conversation between Talaat and Morgenthau mentioned in Ambassador

Morgenthau's Story for which there is no basis, either in the 'Diary' or the

'Letters.' In short, this appears to be rioting more than an attempt to further

darken the already fully tarnished image Morgenthau has painted of Talaat Bey.

It is upon closer examination of the Morgenthau Papers that an even more disturbing

explanation for Morgenthau's having included this bit of fiction in his book,

suggests itself. When one goes back over the 'Diary' entries prior to the period of

the Armenian deportations, i.e., prior to April 24, 1915, one sees that Morgenthau

did in fact discuss the affairs of one the companies named in his book with Talaat

Bey. On April 3, 1915 (a full three weeks prior to the beginning of the

deportations), we see the following entry:

"Called on Talaat at Minister of Commerce's Office, spoke to him about 'New

York Life Insurance Company's funds. 74

Can it be that it was this two line entry in Morgenthau's Diary which served as the

springboard from which Hendrick constructed the alleged conversation discussed

above? As in the discussion on Talaat Bey reading Morgenthau's cables and suggesting

that money earmarked for Armenians be given to his government, is it possible that

Hendrick has simply fabricated (presumably with the connivance of Morgenthau) this

entire episode? Once again, the answer is, yes. While there was an issue involving

funds belonging to the New York Life Insurance Company which had been frozen in

Turkey, it had nothing to do with Ottoman Armenians. To the contrary, a series of

entries in Morgenthau's 'Diary' for the months of March and April 1915 allow us to

state categorically that the issue was just the opposite of what was portrayed in

the book.

We may summarise the 'Diary' entries relative to the 'New York Life Insurance

Company' issue, as follows.

1) On 24 March, a Mr. Feri, the Constantinople representative of the Insurance

Company, paid a visit to Morgenthau and informed him that the Ottoman Government was

refusing to release their bank accounts because their company headquarters was in

Paris, France (a country with which the Ottoman Empire was then at war);75

2) On 29 March, Morgenthau took up the company's problem in a discussion with Talaat

Bey, who informed him of the following: "as to the New York Life funds, the

company had never registered and they don't want them to withdraw their funds, as

they fear that they would not pay their losses here; 76

3) As noted above, on 3 April, Morgenthau's 'Diary' notes that he "called on

Talaat at Minister of Commerce's office; spoke to him about New York Life Insurance

Company's funds; 77

This then is the extent of references to the New York Life Insurance Company funds

in the Morgenthau papers. The March 29, 1915 entry makes it clear that, far from

wanting to serve as the beneficiary of deceased policy holders, Talaat's and the

Turkish Government's interest was in making sure that the company maintained enough

capital in Turkey, so as to guarantee their ability to pay any future claims which

might arise under their coverage.

Simple logic tells us Morgenthau's account must be false, as his 'Diary' establishes

that throughout his tenure in Constantinople, the New York Life Insurance Co. had

its own representative in the Ottoman capital; that is, had Talaat Bey wanted a list

of their clients he had only to demand it. 78

Once again, the question we must ask is: Why does this passage

appear in Ambassador Morgenthau's Story in the first place? In addition to the by

now obvious aim on the part of Morgenthau, namely, to blacken the reputation of

Talaat Bey in every conceivable fashion and whenever possible, there may well have

been an even more venal reason for the inclusion of this passage. A thorough reading

of the Morgenthau papers shows that at the very time Morgenthau's book was being

written he was also a member of the Board of Directors of the Equitable Life

Assurance Society of New York. 79 Indeed, his 'Diary' for the year 1918 shows that

on March 21 he attended a meeting of the Equitable Life Assurance Company at 12:00

and then met with Burton J. Hendrick at 2:30 80 (presumably to work on the

manuscript). Morgenthau, who had been elected a member of the Society's board at ifs

December 1,1915 meeting, 81 was very proud of his being so recognised and even wrote

his son Henry Jr. to the effect that: "I think my selection as one of the

Trustees of the 'Equitable Life Assurance Society' shows that the financial powers

are already realising that my name and advise [sic. advice] will be of some value.

82 It may well be that the passage in question was nothing more than a 'plug' for

the life insurance business. By naming the 'Equitable Life Assurance Society' and

praising Armenians for having the foresight to insure their lives, Morgenthau may

simply have been throwing in a free advertisement for his fellow trustees who had

the good sense to recognise back in 1915 that, in his words "my name and advise

will be of some value." While there is no way to advance this suggestion beyond

the realm of hypothesis, one thing is clear - there is nothing in the Morgenthau

papers to suggest that the alleged conversation between Talaat Bey and Morgenthau

ever transpired.

8) Not satisfied with relating fictitious conversations between himself and Talaat,

Morgenthau also at times simply brings together events which transpired on separate

occasions, thereby creating a totally erroneous impression. A case in point of this

technique concerns the most serious discussion Morgenthau ever had with Talaat on

the treatment of the Armenians. This talk, which occurred on August 8, 1915, took

place at the initiative of Talaat who sent word to Morgenthau (through their mutual

friend, the Grand Rabbi Haim Nahoum) that he wanted to see the American envoy alone,

that is, without his Armenian escort-interpreter Arshag K. Schmavonian as he desired

to discuss "Armenian matters. 83

Morgenthau's version of this meeting in his 'Story' begins as follows:

"In the early" of part of August...he sent a personal messenger to me,

asking if I could not see him alone he said that he himself would provide the

interpreter. This was the first time that Talaat had admitted that his treatment of

the Armenians was a matter with which I had any concern. The interview took place

two days afterward. It so happened that since the last time I had any visited Talaat

I had shaved my beard. As soon as I came in the burly Minister began talking in his

customary bantering fashion.

'You have become a young man again,' he said: `You are so young now that I cannot go

to you for advice any more.'

'I have shaved my beard,' I replied, 'because it had become very grey — made grey

by your treatment of the Armenians."'

In actual fact, the 'beard incident' occurred not in the course of the August 8,

1915 meeting on 'Armenian matters,' but rather a month earlier on 3 July when

Morgenthau's 'Diary" records the following:

"...Talaat teased me about having shaved beard and said I had become young and

he would no longer take my advice...I told him I shaved it because it grew grey on

account of treatment of Armenians. 85

By juxtaposing the banter of the 3 July conversation with the very serious

appointment on the "Armenian matters" which occurred a month later,

Morgenthau creates the impression that Talaat was not very serious in asking him to

come discuss the Armenian question on 8 August. How could he be serious when he

began a talk about life and death matters by joking about Morgenthau's beard?