|

|

The following valuable article is

from the tetedeturc.com site, and it was only discovered by

accident, through an unrelated search. This Turkish site in France excels,

when compared to the many other run-of-the-mill Turkish "genocide"

web sites, because the operators of tetedeturc ("Turk's head")

actually take the trouble to dig up original material. It's too bad the site

is in French, and this material is unavailable to those of us who follow the

universally imperialist language of English.

The following unofficial translation is poor, mainly brought to you by

the automatic translation service that you can see from the flags at left, and

is only meant to give the gist of what is being said. To get at the purer

original, readers are advised to consult the original French, the link for

which has been provided above.

What's below is a remarkable telling of history, because practically

everything the French historian wrote is in alignment with "Turkish

propaganda," and yet Gaillard could not be accused, by any stretch of the

imagination, to be an "agent of the Turkish government,"

particularly when the government at the time of his authorship was

next-to-nonexistent, for all practical purposes, as the puppet Ottoman Turkish

government was under the domination of the British and the French. And

it's not that the author did not write from an Armenian slant, and relied on

Armenian sources; note his constant description of the area in question as

"Armenia," a common practice among Westerners of the period, even

though there was no "Armenia" at the time; Gaillard also accepted

Armenian figures for the worldwide population at the time as over four

million, when the reality was closer to three million, and for the Ottoman

Empire itself, the wildly propagandistic 2.3 million.

Note the accurate historical points that are made, totally contradicting the

claims of Armenian propaganda:

- Since the 14th century, Turks and Armenians co-existed rather well,

until roughly 1878.

- The role of the terrorist organizations in spoiling relations, and how

the Patriarchs cooperated with them.

- How the treacherous Armenians pledged themselves to Russia.

- Most Ottoman-Armenian soldiers crossed over to the Russians.

Interestingly, note the usage by the Armenian-British Committee that what

took place "among the various local races," at the behest of the

Ottoman government, amounted to civil war ("la

guerre civile"). This is a term that Vahakn Dadrian and other

Armenian propagandists abhor

when applied to what took place between the Armenians and the Turks, to

preserve the image that the Armenians were all poor, innocent lambs. How

ironic that the very term was good enough for the Armenians of the period, in

a most related context.

Do bear in mind that the Tachnaktzoutioun in the text, and the "Tachnakistes"

refer to the Dashnaks, and the "Hintchakistes"

are, of course, the Hunchaks.

The introduction directly below is a not complete version of what the Turk's

head web site operators had to say.

|

|

|

| |

The text below is extracted from the book of Gaston Gaillard, "The

Turks and Europe" ("Les Turcs et l'Europe"), published in 1920 by the

Librairie Chapelot in Paris. The French historian, Gaston Gaillard, specialized in the

Balkans and the Middle East, and his books included, "Le Mouvement Panrusse et les

Allogènes" (1919), "L'Allemagne et Le Baltikum" (1919) and "La

Fin du Temps" ("The End of Time," 1933). In "The Turks and

Europe," the author analyzes "The Dismemberment of the Ottoman Empire"

in chapter VII, beginning with the "Turco-Armenian Question" (pp. 264 to 297).

According to Gaillard, the Turco-Armenian question is inseparable from the "Question

of the East" as a whole, and was made more critical by the policy of the Allies

"which, after having carried out the dismemberment of Turkey, did not seem to have

renounced the rejection of the Turks in Asia." The detachment of Armenia from the

Ottoman Empire, according to the author, within the framework of this policy of

"rejection" of the Turks, awakened the movements of pan-Turkism and pan-Arabism.

Not very known by the general public, the book of Gaston Gaillard sheds very interesting

light on the historical Turco-Armenian disagreement, rupturing from the single thought

which the Armenian lobby in France imposes on us.

Thanks to Professors Nuri Bilgin and Mustafa Oner for their invaluable contribution to the

realization for this page. Good reading!

The team of Turk's Head

March 11, 2003

|

THE TURCO-ARMENIAN

QUESTION

|

The Armenian question, which so deeply disturbed Turkey and complicated the question

of the East, has in its origins Russia's covetousness of Asia Minor and comes from

the interference of the latter in Turkish affairs under the pretext of protecting

the Armenians. This question, as the difficulties prove was raised as a result, is

one of the factors feeding the antagonism of the Slavs and the Turks and served as

an episode of the conflict, supporting the blockage of the descent of the Slavs

toward the banks of the Mediterranean, which the Russians always sought to reach

either by way of Asia Minor or Thrace, or simultaneously by these two ways.

Mahomet II , after the conquest of Constantinople, had however instituted, in 1461,

a patriarchate in favor of the Armenians. Different rights were granted to them

various times by imperial decrees.

Of the religious Armenians of Calcutta, benefiting from freedoms which they enjoyed

in India, at the beginning of the XVIIIth century, were Aztarar , Novelist, the

first newspaper which appeared in the Armenian language, and, at the end of the same

century, Mékhitharistes appeared in Venice Yéghanak Puzantian, the Byzantine

Season. About the middle of the XIXth century, the same monks published a literary

and documentary review, Pazmareb, which still appears nowadays. The Protestant

Armenians also published a review of propaganda, Chtémaran bidani Kidéhatz, in

Constantinople and, in 1840, the first big national daily in the Armenian language,

Archalouis Araradian, the Dawn of Ararat, appeared in Smyrna.

|

|

|

Patriarch Khrimian

|

In 1857, in the monastery of

Varag, close to Van, Miguidirtch Krimian, who became patriarch and catholicos later,

founded a printing works. Under the name of Ardziv Vaspourakan , the Eagle of

Vaspourakan, he published a monthly review to support the cause of Armenian

independence, and, at the same time, in Mush, printed a similar publication Artsvik

Tarono , the Eaglet of Taron. The Armenians of Russia also started about the same

time various publications, such as Hussissapaц╞l , the Aurora borealis,

review published in Moscow in 1850 , and several newspapers with Tiflis and Bakou.

The Armenians of Russia also started towards the same one to make appear time

various publications, such as Hussissapail, the Aurora borealis, a review published

in Moscow in 1850, and several newspapers in Tiflis and Baku. In 1860 , the

authorization was granted to the Armenians to constitute an Armenian national

Assembly to discuss and regulate their religious and national affairs.

Since the XIVth century, until this time, the Armenian element lived in good

understanding with the Moslem element, and even the Armenians persecuted in Russia

came to take refuge in Turkey. The Turks, who had found Armenians but not Armenia,

because the latter had a very troubled history, with quite short periods of

independence and changing borders, and the Armenians, which had successively

undergone Roman, Séleucide, Persian and Arabic dominations, lived peacefully for

six centuries with the Turks.

But since 1870, a group of young people gave a new strength at the same time as

another orientation to the movement created and maintained by the Armenian monks and

published in Constantinople works in favor of the Armenians.

In 1875, Portakalian founded the first Armenian revolutionary committee and

published a newspaper, Asia. Shortly after the Araratian committee was constituted,

which aimed at establishing close connections between the Armenians of Turkey and

Russia, then other[s followed], Tebrotssassiranz, Arévélian and Kilikia.

Concurrent to those, committees were created with an aim of charity or economy such

as 'the Association of devotees' and 'the Charitable organization,' founded in 1860,

which proposed the development of Cilicia and collected important sums; these were

not without an important role in the Armenian movement.

The Armenian question started to really arise and soon took an acuity which did

nothing but grow, in 1878, following the Turco-Russian war, at the moment when

Turkey had to face serious difficulties, interior as well as external; this question

was covered by article XVI of the Treaty of San Stefano of July 10, 1878 and article

61 of the Treaty of Berlin.

|

| |

Article XVI of the Treaty of San Stefano, written at the request of the Armenians and

proposed by the Russian plenipotentiary, stipulated that "the Sublime Porte is

committed in carrying out, without more delay, the administrative autonomy required by the

local needs in the provinces inhabited by the Armenians." The Turks, who could

not admit the formula "administrative autonomy", asked that this should be

replaced by that of "reforms and improvements," but the Russians then required

as a guarantee the occupation of Armenia by the troops of the Tsar. The Congress of Berlin

removed this clause of guarantee and replaced the drafting suggested by Russia by the text

proposed by Turkey.

With an aim of acquiring a moral influence on the Armenians in Turkey in order to secure

domination of the region, the Orthodox [people] pledged themselves to tsarism, and worked

toward being recognized as a higher authority by the patriarchate of Constantinople, and

succeeded there, helped by Russian political agents. One was not going to be long in

realizing that the purpose of the fastening of the catholicos to the patriarchate of

Constantinople was to create a hostile current in Turkey within the Armenian populations

of Russia and Asia Minor, and that this movement, as we will see, was going to appear

anti-Turkish.

At the time of the arrival of the Russians to the doors of Constantinople at the end of

the Turco-Russian war, Nerses Varzabedian who had succeeded Khrimian, went to the Grand

Duke Nicolas with a delegation and a memorandum given to him in which, after having

enumerated the objections of the Armenians against the Ottoman government, he asked "that

one proclaim the independence of the Eastern provinces of Asia Minor inhabited by

Armenians, or, at least, that these provinces pass under the control of Russia."

A delegation made up of four prelates was sent by Europe in Rome, in Venice, in Paris and

in London to ensure itself of the contest of the powers and those met at the Congress in

Berlin. Their steps, the purpose of which were to obtain the maintenance of article XVI of

the Treaty of San Stefano, only managed to insert article 61 in the Treaty of Berlin.

It is only towards 1885 that one intended to speak for the first time about what one

called thereafter the Armenian movement, and which the Armenian revolutionists having

taken refuge in England, in France, in Austria and America started to launch publications,

to form committees, to protest against alleged Turkish exactions and to denounce the

violation of the Treaty of Berlin.

These ideas of independence quickly made more and more progress, and the prelates who,

after the death of Nerses, were known for their Turcophile feelings, like Haroutian

Vehabedian, bishop of Erzeroum, elected official patriarch in 1885, saw themselves

abandoned by the Armenian clergy and were soon in opposition with the members of the

committees.

In 1888, Khorene Achikian, who succeeded Vehabedian, was also accused of Turcophilia and

the committees endeavoured to replace him with Narbey who had formed part of the

delegation sent to Europe at the time of the Congress of Berlin.

This Armenian movement necessarily caused between the various elements of the population

the incidents which grew considerably worse and carried then by the bishops and the

consuls with the knowledge of the European powers as the consequence of the cruelties

exerted by the Turks.

|

|

Following the Turco-Russian war, the revolutionary

agitation which occurred in Russia and in the Caucasus made its repercussion felt

among the Armenians, and the Tsarist government , by measurements of rigor which it

then took, did nothing but revive this agitation by increasing the dissatisfaction

of the Armenians.

Migiurditch [Migirdich] Portakalian*, teacher from Van,

came to Marseilles and in 1885 published the newspaper Armenia. Minas Tcheraz made

its appearance at the same time in Paris, another newspaper under the same name.

These publicists, so much in these bodies than by the conferences, claimed the

application of article 61 of the Treaty of Berlin.

In 1880, revolutionary committees were formed in Turkey. In 1882, "the

Association of the armed Men" was based in Erzeroum, and dissolved in 1883

following the arrest of some of its members.

An uprising took place in Van, in 1885, at the time of the election of a bishop, and

insurrectionary movements occurred in Constantinople, Mush and Alachkehr, under

various pretexts.

* (Holdwater: Portakalian is credited with the

founding of the group Armenakan, but it was actually nine of his students who

established it: Migirdich Terlemezian (Avetisian), Grigor Terlemezian, Ruben

Shatavarian,Grigor Adian, Grigor Ajemian, M.Bratjian, Gevord Hanjian, Grigor

Beozikian, and Gareghim Manukian. Others who read Portakalian's newspaper were

inspired to set up the Hunchak Party.)

|

| |

The following year, in 1886, a certain Nazarbey*, originating in the Caucasus , and his

wife Maro, created, in Switzerland, Hintchak, the Bell, a social democratic committee

proposing to grant the Armenians an autonomous administration, and founded in London a

monthly body of the same name. This committee intended to reach that point not by the

intervention or the mediation of the European powers which it considered useless to appeal

to again, but by the only action of its organizations in all the country, charged to

collect funds, to equip the men to foment disorders, and at the convenient period, after

having weakened the government, to carry out its aspirations.

The Hintchak committee ensured itself of the representatives in all the large cities such

as Smyrna, Aleppo, Constantinople, and its organization was completed in 1889.

In 1890, at the instigation of Hintchakistes, a revolt burst in Erzeroum and the incidents

occurred in various localities. To Constantinople, armed demonstrators, preceded by the

Patriarch Achikian, moved towards the Sublime Porte to present their objections, but were

dispersed, and the reproached patriarch's correction was to resign thereafter.

Indeed, the Hintchak committee, which was not without finding support material from the

representatives of the powers and mainly of those of Russia and England, continued its

intrigues and redoubled their activity.

|

|

Matheos Izmirlian |

Sunday March 25, 1894, Samsoun, in the court of the church, a

certain Agap, of Diarbekir, who had been selected by the Hintchak committee to assassinate

the Patriarch Achikian, to which the committee reproached for maintaining the correct

relationship with the Ottoman government, shot at the prelate a blow from a revolver which

did not reach him. Following this attack, Achikian resigned and Matheos Ismirlian, who was

supported by the committees, was elected patriarch thanks to the pressure exerted by the

latter on the French National Assembly. Matheos Ismirlan took at once the chair of

Hintchak to which it gave a new extension, and a little later was named president of the

ecclesiastical council of the patriarchate and then the catholicos of Cilicia, a priest

named Kirkor Aladjan, which had been revoked and sent from Constantinople after having

insulted the governor of Mush.

* [Holdwater: Avetist Nazarbek, or

Nazarbekian]

|

(The committees stepped up

their activities) benefiting from the tolerance of the Ottoman government and its

benevolent provisions with regard to the Armenians, devoting itself to active

propaganda against the Turks.

|

Some Armenians, who felt that the program of the "Hintchak" committee did

not satisfy, founded in 1890, a new association under the name of "Trochak"

which took, later, that of "Tachnakizoutioun," and published the Trochak

newspaper . The members of this committee had recourse to the threats and terror to

obtain the money which was necessary for them and did not feel reluctant to

assassinate people who refused to go to along with the injunctions of the committee.

In 1896, the committees attempted an armed attack against the Ottoman Bank. Armed comitadjis*

from Europe with Russian passports, made an [eruption] at the Ottoman Bank and were

dispersed by the governmental troops. But the promoters of the attack were not

stopped thanks to the protection which was granted to them by the Russian and French

authorities. Escorted by Maximof, of Armenian origin, first dragoman of the embassy

of Russia, and Rouet, first dragoman of the embassy of France, they were brought

aboard the steamer "the Gironde," of the Maritime Transport. The members

of the "Trochak" retrenched in the churches of Galata, of Samatra and the

Patriarchate beseeched the grace of the government, while Arméne Aktoni, one of the

chiefs of the committee, committed suicide, after having awaited the arrival of the

English fleet [boat] of Soulou-Monastir, in Samatra.

The bishops continued, not without success, to request the contest of the Russian,

English and French consuls; however, Monsignor Ismirlian, who had sent an ultimatum

to the imperial Palace and continued his intrigues, finally was revoked in 1896 and

was sent to Jerusalem.

At that time, Armenians left in great number for Europe and America, and the

Catholicos of Etchmiadzine sent to the Conference of the Hague delegates to expose

the Armenian question in Turkey. These committees, which deployed such an activity

in Turkey, did not undertake anything in favor of their compatriots in Russia.

The committees which had founded themselves during or before the patriarchate of

Nerses under the names of "Ararat", "the East", "Friends of

the Instruction", "Cilicia", had amalgamated themselves in 1890 under

the name of "Miatzal Anikéroutioun Hayotz", and this association

continued to extend the organization of committees to the smallest localities,

benefiting from the tolerance of the Ottoman government and its benevolent

provisions with regard to the Armenians, devoting itself to active propaganda

against the Turks.

This propaganda was assisted by the Armenian bishops in the Eastern provinces, where

they endeavored to cause a European intervention. On their end, the Russians,

continuing their dream of domination of the Orthodox Church at the same time as that

of the absorption of Armenia, pushed the Armenians by all the means against the

Turks, and encouraged them to carry out their national ideal, thus more easily

attracting them under Russian domination.

* [Holdwater: committee-men]

|

| In

1905-1906, the maneuvers of the Armenian committees managed to create an animosity

between Kurds and Armenians, to which no series of reform seemed able to put an end. |

The action of these committees was, as we will see, very important in the events which

proceeded in Asia Minor.

Insurrections, traces of which were found since 1545 and which lasted until the

proclamation of the Constitution in 1908, continuously took place in the mountainous area

of Zeitun. These insurrections were favored by the form of the feudal administration which

had been maintained in this area. Each of the four districts of Zeitun was controlled by a

chief who had taken the title of "ichehan," prince, a kind of lord to which the

Turkish villages were to pay a royalty received by special clerks*. The action of the

committees did not fail to make profitable this state of affairs, and it is only in 1895

that the Ottoman government put an end to it

The Armenians had already refused the payment of the taxes and had revolted on several

occasions between 1782 and 1850, time to which the Turks exasperated by plunderings and

the exactions of the Armenian mountain dwellers gave up their goods and emigrated. Until

there the revolts of Zeitoun could be allotted to the administration of the "ichehan."

But the instigators of the Armenian movement were not long in being useful themselves of

these continual disorders and soon gave them a new character. This movement was encouraged

and largely supported by Armenians who lived abroad, and, in 1865, following alleged

exactions of the Turks, the nationalist committees rose against the government to claim

the independence of Zeitun. The revolts followed one another then without discontinuity

until that which the Hintchakistes determined in 1895 and which lasted 45 days.

In 1890, the committees "Hintchak" and "Tachnakzoutioun" had caused

insurrections with Erzeroum, and, in 1894, in Sassoun, where the attack against the

Achikian patriarch took place about which we spoke of earlier. In 1905 Tachnakistes began

a new insurrection there. The rebellion gained Amassia, Sivas, Tokat, Mush and Van, and

the committees worked to extend and worsen it. In 1905-1906, the maneuvers of the Armenian

committees managed to create an animosity between Kurds and Armenians, to which no series

of reform seemed able to put an end. For the remainder of 1909-1910, at the time of new

disorders, the revolutionary chiefs openly attacked the Ottoman troops.

Two years after the confiscation and the handing-over with the Ottoman government of the

movable property and buildings belonging to the Armenian churches which had taken place on

June 21, 1903, Batoum was, February 6, 1905, the theatre of massacres, and those were

renewed then in Erivan, Nakhjivan, Choussa and Caussak. In 1908, the government of the

Tsar made a violent oppression of all the Caucasus and an ukase ordered the election of a

new catholicos, in the place of Mgr. Khrimian, who died in October 1907. Mgr Ismirlian was

named to succeed him in 1908. At this time, Russian tyranny was felt so hard that the

Tachanakistes took refuge in Constantinople, where the Young Turks did not hesitate to

give an opinion in favor of the Armenians of Russia.**

* (Holdwater: we are frequently told

how the eastern Armenians needed to pay off the persecuting Kurdish tribes. Here, we learn

the Turks were paying off the Armenians of Zeitun. The following paragraph makes clear the

extent to which the Turks were persecuted by these "mountain Armenians," finally

forcing them to leave the area.)

** (The Dashanks fled the tyranny of Russia, for the safe refuge of the Ottoman Empire.

The irony could not be greater.)

|

Since 1905, the Armenian committees had decided, in a Congress held

in Paris, to put to work all its means to arrive at the independence of Cilicia.

Russia, on its side, actively endeavored to spread orthodoxy among the Armenians ...

in order to extend its zone of influence ... and to thus clear a passage towards the

Mediterranean.

In 1907, the Armenians of

Bitlis, Diarbekir and Harput provided a petition to the consulate of Russia, composed

of more than 200.000 signatures, to ask their admission to Russian subjection.

|

One could believe that after the proclamation of the

Constitution, the committees which had sought to hasten the fall of the empire by an

agitation that would have enabled a foreign intervention, would put an end to their

revolutionary activity and occupy themselves more with social and economic

questions. Sabah-Gulian, originating in the Caucasus, chair of the "Hintchak,"

in a meeting of the Hintchakist committee held in 1908 with the Sourp-Yerourtoutioun

church of Pera, declared, concerning the Hintchak program and of the constitutional

mode: "Us Hintchakistes, fine at revolutionary activity, let us work all of our

forces for the progress of the fatherland." On its side, Agnoni, of Russian

origin, one of the presidents of the Tachnaktzoutioun, proclaimed that "the

first duty of Tachnakistes would be to join their efforts to those of the Committee

Union and Progress to maintain the Ottoman Constitution and to ensure the harmony

and the harmony between the various elements."

The union of the committees was then dissolved, the new situation of the Turkish

empire having brought between them differences in opinion, but, a little later the

Tachnakzoutioun committees, Hintchak, Veragaznial-Hintchak were not long in

reorganizing and in forming new committees in all of Turkey. The Ramgavar *

committee, right of the people, was constituted in Egypt, by Mr. Boghos Nubar, after

the proclamation of the Constitution, and made watch of the greatest activity. This

committee, in March 1914, intended itself to act in liaison.with the "Hintchak",

the "Tachnakzoutioun" and the "Veragazmial-Hintchak." Another

committee, the "Sahmanatragan," also constituted itself. These committees

ensured themselves of the support of the patriarchate and the bishops to harden

their influence and extended their ramifications everywhere in order to obtain the

majority with the elections. They were devoted to an active propaganda to gain the

Armenian public opinion using publications of all kinds: books for the schools,

almanacs, postcards, songs, etc, published in Geneva or in Russia

Since 1905, the Armenian committees had decided, in a Congress held in Paris, to put

to work all its means to arrive at the independence of Cilicia. Russia, on its side,

actively endeavored to spread orthodoxy among the Armenians in the areas of Adana,

Marash and Alexandrette, in order to extend its zone of influence on this side and

to thus clear a passage towards the Mediterranean. With the remainder, the bishop of

Adana, Mochègue, got busy to prepare the revolt which was to explode soon.

The Christians of Armenia thus facilitated the extension of the Russian empire. In

1904-1905, steps were taken by Nestoriens so that Russian priests were sent to them

and [for them] to pass [convert] to orthodoxy. In 1907, the Armenians of Bitlis,

Diarbekir and Harput provided a petition to the consulate of Russia, composed of

more than 200.000 signatures, to ask their admission to Russian subjection.

* (Holdwater: It is believed in

some circles that the Armenakan Party evolved into Ramgavar.)

|

| (Russian

consul in Bitlis to his ambassador in Istanbul writes that the Dashnaks' purpose is to

bring the Russians into the Ottoman Empire, and that) "to arrive at this purpose,

the Dashnaks have recourse to various means and endeavor to bring collisions between

the Armenians and the Moslems and especially

with the Ottoman troops." |

The chief Hintchakiste Sabah-Gulian himself acknowledged, in the newspaper Augah Hayassdan

(Independent Armenia), that the members of the committee had benefited from the negligence

of the Turks to open armories where those were sold at half price, when they were not

given as free.

The Armenian committees benefited from the legislative elections to attempt a new

agitation. They redoubled activity, and, contrary to their engagements, Hintchakistes

parted with the members of the opposition who fled abroad.

At the time of the Balkan war, in 1913, the Tachnakistes committees launched proclamations

against the Ottoman government and the Union party. The consuls of Russia at Erzeroum,

Bitlis, did not dissimulate their sympathies, and, that of Van threatened the vali [Ottoman governor] of the arrival of the Muscovite troops through

Azerbaijan under the pretext of the alleged dangers which the Armenians had to fear on

behalf of the Turks and to restore the order.

But while Russia choked without care at all the attempts of the Armenian committees, it

encouraged and gave an energetic support to those which fomented revolts in Turkey. Of the

remainder, in the report addressed by the consul of Russia to Bitlis, with the ambassador

from Russia in Constantinople, the date of December 24 1912, this one under the No. 63,

informs its government that the intention of the Tachnakistes is "according to their

own terms to bring the Russians here" and which "to arrive at this purpose, the

Tachnakistes have recourse to various means and endeavor to bring collisions between the

Armenians and the Moslems and especially with the Ottoman troops." It quotes in

support of this assertion some facts which do not leave any doubt about its veracity

He wrote, which today singularly clarifies the policy of the Allies:

"Your Excellency will understand that the future conflict between Armenians and

Moslems will depend, partly, on the policy and the activity of the Tachnakzoutioun

Committee, the course of the negotiations of peace between Turkey and the Slavic States of

the Balkans, and, following these negotiations, of the possibility of an occupation of

Constantinople by the Allies. If the deliberations of the Conference of London did not

lead to peace, the approach of the fall of the Ottoman capital would not be without

influencing the relationship between the Moslems and the Armenians of Bitlis.

The Armenians of the cities, as well as those of the country, have, just as their

religious chiefs always testified to their leaning and their affection for Russia and

declared on several occasions that the Turkish Government is unable to maintain order, law

and prosperity. Many Armenians promise, as of now, to offer their churches to the Russian

soldiers to be converted into Orthodox temples.

The current state of Balkans, the victory of the Slavic and Hellenic governments on

Turkey, over-excited the Armenians and filled to their hearts with the hope and the joy of

being delivered from Turkey."

|

A press campaign was made at

the same time by the Armenian newspapers of Europe, Constantinople and America and, in

particular, by Agadamar, organ of the Tachnaktzoutioun committee, which did not feel

reluctant to launch all kinds of calumnies against the Turks and to announce so-called

attacks.

|

The sending to Bitlis of a Commission made up of Armenians and Turks, chaired by an

English[man], for the application of the reforms in the Turkish provinces close to

the Caucasus, was not, as well one thinks, to satisfy the Armenians and the Russians

who had sacrificed many soldiers to assure the possession of it.

Benefiting from the difficulties of the Ottoman government after the Balkan war, the

committees reflected agreement to again raise the question of the "reforms of

the Eastern provinces." A Special subcommittee, which had as a president M.

Boghos Nubar, was sent by the Catholicos of Etchmiadzine attached to the European

governments to support the Armenian claims. A press campaign was made at the same

time by the Armenian newspapers of Europe, Constantinople and America and, in

particular, by Agadamar, organ of the Tachnaktzoutioun committee, which did not feel

reluctant to launch all kinds of calumnies against the Turks and to announce

so-called attacks.

In 1913, Russia took the initiative of a project of reforms to be introduced in

Armenia. She made Mr. Giers* communicate with the Conference of the six ambassadors

which entrusted the study of [the reforms] through a commission. German and Austrian

representatives being shown unfavorable to the Russian project before this

commission of the Armenian reforms which meets of June 20 to July 3, 1913 with the

embassy of Austria-Hungary at Yeni-Keni; Russia, following this failure, endeavored

to lead Germany to accept its point of view.

*(Holdwater: Mikhail Nikolayevic von Giers was

the Russian ambassador in Istanbul. From Ambassador Morgenthau's Story book:

"Giers... was a proud and scornful diplomat of the old aristocratic régime. He

was exceedingly astute, but he treated the Young Turks contemptuously, manifested

almost a proprietary interest in the country, and seemed to me already to be

wielding the knout over this despised government." A knout is a "leather

scourge formerly used for flogging criminals in Russia.")

|

| |

Mr. Giers and Mr. Wangenheim fell from agreement in September 1913 on a program to which

the Sublime Porte opposed a counter-proposal. However the representatives of Russia

managed to conclude between January 26 and on February 8, 1914, a Russo-Turkish agreement.

|

|

Russian

Foreign Minister

Sergei Sasonov was

fired

by Tsar Nicholas in 1916. |

When the

plan of the reforms was outlined and that attributions and the competence of the

inspectors and their personnel were determined, the Catholicos addressed a dispatch of

congratulations to Mr. Boghos Nubar and this one sent another of them to Mr. Sasonov,

because the Armenian committees regarded the results obtained as a first step taken

towards autonomy. Encouraged by this first success, the committees stepped up their

activity. The Tachnaktzoutioun transferred its seat to Erzeroum and a congress was

established. The Hintchak committee sent to Russia and to the Caucasus several of its most

influential members to collect funds, in order to foment a rising with an aim particularly

of reaching the Union party and Progress and of reversing the government. Meanwhile, the

war exploded.

|

(The

Hunchaks and Dashnaks instructed) that if the Russians advanced, all the means were to be employed to

obstruct the retirement of the Ottoman troops, to disrupt their supply and that, if

the Ottoman army advanced, the Armenian soldiers were to give up their formations, to

constitute bands and to join to the Russians.

...The majority of the

Armenians which were mobilized crossed over to the Russian side, where after being

equipped and being armed again, they were sent against Turkey.

...The Armenians did not

answer the call of the mobilization and prepared for the insurrection while waiting

for the arrival of the Russians.

|

The patriarch, serving as the representative of the Armenian nation, brought

together in council, under his presidency, the chiefs of Tachnaktzoutioun, Hintchak,

Ramgavar and Vergazmial-Hintchak, and the members of the Armenian French National

Assembly affiliated at these committees, to intend itself on the attitude to adopt

if the Ottoman government would take part in the war. No decision was made, as

reserved Hintchakistes and Tachnakistes preferred to await the turning of events.

However each of these committees continued on their end their activity and

transmitted to the provinces the instructions saying that if the Russians advanced,

all the means were to be employed to obstruct the retirement of the Ottoman troops,

to disrupt their supply and that, if the Ottoman army advanced, the Armenian

soldiers were to give up their formations, to constitute bands and to join to the

Russians.

The committees benefited from the situation in which the Ottoman government hardly

left a disastrous war and engaged in a new conflict to determine insurrections in

Zeitun and in the sandjak of Marash, Cesaree and especially in the vilayet of Van,

and that of Bitlis, in Bitlis, Talori and Mush, and that of Erzeroum. In the sandjak

of Erzeroum and Bayezid, after the order of mobilization, the majority of the

Armenians which were mobilized crossed over to the Russian side, where after being

equipped and being armed again, they were sent against Turkey. It was the same in

Erzindjan, where three quarters of the Armenians passed to Russia. Armenians of the

vilayet of Mamouret' ul Aziz (Harput), where the Moslems were also attacked and

where weapons were gathered, provided many recruits to the battalions directed by

Russia towards Van and the Persian border. Many emissaries had been sent out of

Russia and Constantinople to Dersim and its surroundings to rouse the Kurds against

the Othoman government. It was the same in the vilayet for Diarbekir, where the

Armenians were however in a minority. One discovered there deposits of weapons of

all kinds at the same time as of many refractories.

In the area of Kara-Hissar, where they had tried small revolutionary movements

during and after the Balkan war, the Armenians did not answer the call of the

mobilization and prepared for the insurrection while waiting for the arrival of the

Russians.

Similar incidents: insubordinations, attacks against the Turks, threats with the

families of the mobilized Moslems, occurred in the vilayet of Ankara. In the vilayet

of Van, when the Russians, which had joined Armenian volunteers, undertook an

offensive movement, Armenian peasants gathered and prepared themselves to attack the

Ottoman civil servants and gendarmes. At the beginning of 1915, revolts took place

with Kevache, Chatak, Havassour and Timar and were propagated out of Ardjitch and

Adeldjivaz. In Van, more than five thousand had risen, of which seven hundred of

them attacked the fortress, jumped the military and governmental buildings, those of

the Ottoman Bank, the national Debt, the Control of the Tobaccos, the mail and

telegraph Stations and put fire to the Moslem district. This insurrection was calmed

towards the end of April. Many Armenian bands, ordered by Russian officers, then

tried to cross the border on the side of Russia and Persia.

|

| But one

cannot accept information which claims that the figure of the Armenians massacred by

the Turks would rise to more than 800.000, and who do not speak about the Turks

massacred by the Armenians. |

|

|

Grand Duke

Nicholas Nikolaevich |

After the capture of Van, the Armenians offered a banquet to General

Nikolaevich, commander-in-chief of the Russian army of the Caucasus, who in the speech he

made on this occasion, declared: "Since 1626, the Russians always worked to

deliver Armenia, but the political circumstances prevented them from succeeding. Today as

the grouping of the nations has radically changed, one can hope that the release of the

Armenians will be achieved." Aram Manoukian, known as Aram pasha, that General

Nikolaevich named as provisional governor of Van, answered: "When one month ago we

began our uprising, we counted on the arrival of the Russians. Our position was very

perilous. We had to return or die. We preferred to die, but, at one unexpected time, you

have run to our help."

|

|

Aram

Manoukian

|

The Armenian bands obliged the Ottoman government to distract a part

of its troops to repress their carried out revolution in the vilayet of Brousse and its

surroundings. In Adana, as in the other provinces, the Armenians made all kinds of

insurrectionary preparations.

Responding to these attempts at revolt, the Turkish Government ordered military

expeditions which, considering the circumstances, were shown without pity and devoted to a

pitiless repression. An order of the Turkish Government of 20 May 1915, relating to the

changes of the places of residence of the Armenian populations, comprised measurements for

the deportation of the Armenians. Considering the negligence of the Turks and the similar

methods which had been employed by the Germans on the Western face, one can however wonder

whether these measurements were not suggested to them by the latter.

Tahsin pasha, governor of Van, was replaced by Djevded bey, brother-in-law of Enver, and

Khalil pasha, another relative of Enver, and received the command of the Turkish troops of

the area of Ourmiah. Talat named Mustapha Khalil, his brother-in-law, in Bitlis.

By an inevitable sequence and their reciprocal repercussions, the insurrectionary

operations of the Armenians which called repressive measurements on behalf of the Turks

revived existing disagreements and to create a deplorable situation for the ones and the

others. It is understood that, under such conditions, ceaseless conflicts rose between

these two elements of the population, that in turn there were reprisals on one side and

the other, after the Turco-Russian war, the events of 1895-1896, at the time of the

conflict of Adana, during the Balkan war and the last war. But one cannot accept

information which claims that the figure of the Armenians massacred by the Turks would

rise to more than 800.000, and who do not speak about the Turks massacred by the

Armenians. This figure does not correspond to reality and is obviously exaggerated, since

the number of the Armenians, which was approximately 2.300.000 for all the Turkish empire,

did not exceed before the war, in the Eastern provinces, 1.300.000 and which the Armenians

still claim to be in a sufficient number to constitute a State. According to the Armenian

statistics, before 1914, there were approximately 4.160.000 Armenians of which, apart from

the 2.380.000 that accounted for the Ottoman Empire, 1.500.000 were part of the empire of

Russia, 64.000 lived in the provinces of the shah of Persia and in the colonies abroad and

approximately 8.000 in Cyprus, in the islands of the archipelago, Greece, Italy and

Western Europe.

|

|

One cannot better make besides, in response to the sharp and ceaseless complaints

made by the Armenians or presented at their instigation, that to return to the

Report entitled, Statistics of the provinces of Bitlis and Van, of General Mayewsky, consul general of

Russia initially with Erzeroum during six years then with Van, and representative of

a power which had been always shown fundamentally hostile to Turkey. He wrote:

"Without exception, the allegations of the publicity agents, according to

whom the Kurds would work to exterminate the Armenians, must be rejected as a whole.

If they were founded, it had been necessary that not an individual pertaining to

another race had not been able to exist among the Kurds and that the various people

living in the medium of them had been in the need for emigrating in mass, fault of

being able to get a piece of bread or to become their slaves. However, neither one

nor the other of these situations were carried out. On the contrary, all those who

know the Eastern provinces will attest that, in these regions, the villages of the

Christians are in any case more prosperous than those of the Kurds. If the Kurds

were only brigands and robbers, as Europeans claim, the state of prosperity of the

Armenians, which lasted until 1895, would never have been possible. Thus, until

1895, the distress of the Armenians in Turkey is only one legend. The state of the

Ottoman Armenians was not worse than that of the Armenians being in other countries.

The complaints whereby the state of the Armenians of Turkey would be intolerable

hardly bring back to the inhabitants cities, because those enjoyed their freedom

from time immemorial and were favored under all the reports. As for the peasants,

with a perfect knowledge of the agricultural work and artificial watering, their

condition was better by far than that of the peasants of central Russia.

As for the Armenian clergy, its efforts about religious teaching are null. On the

other hand, the Armenian priests worked much to cultivate the national ideas. In the

interior of the mysterious convents, the teaching of the hatred of the Turk took the

place of the devotions. The schools and the seminars contributed largely to this

work of the religious chiefs."

Following the Russian rout, the Armenians, Georgians, and the Tartars formed a

Transcaucasian Republic which was to have only a transitory existence, and we

exposed elsewhere the attempt made jointly by these three States to safeguard their

independence.

|

| |

The Government of the Soviets published, January 13, 1918, a decree stipulating in its

article 1. "The evacuation of Armenia by the Russian troops and the immediate

formation of an army of Armenian militia with an aim of guaranteeing the personal security

and the materials of the inhabitants of Turkish Armenia," and in its article 4, "the

formation of an Armenian provisional Government in Turkish Armenia, in the form of a

council delegated by the Armenian people, elected on the democratic basis," which

obviously could not give satisfaction to the Armenians.

Two months after the promulgation of this decree, the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, in March

1918, stipulated in its article 4 that "Russia will do all in its capacity to

ensure the fast evacuation of the Eastern provinces of Anatolia and their restitution in

Turkey. Ardahan, Kars and Batoum will be evacuated without delay by the Russian

troops."

The Armenians were shown all the more dissatisfied and anxious following these events that

not having concealed their hostility to the Turks and their satisfaction to be withdrawn

from their domination, they feared their renewed attack and that those at the very least

took again the provinces which they had lost in 1878.

In April of the same year, the fight started again and successively Trebizond, Erzindjan,

Erzeroum, Mush, Van fell to the hands of the Turks. Following the talks started by

Georgians with the Turks and of the negotiations that occurred, the Armenians constituted

a republic on the territories of the area of Erivan and the Lake Sevan.

Following the discussion of the Armenian question at the Peace Conference and the long

exchanges of views which had taken place, Mr. Wilson, in August 1919, directly

addressing the Ottoman government, put it in residence to prevent any massacres of

Armenians and informed it that, if the government of Constantinople would not succeed

there, it would cancel the twelfth of the fourteen points of his program envisaging the

maintenance of Turkish sovereignty, which, one must notice while passing, became

contradictory with other points of the same program and in particular with the principle

of the famous right of the people to conceive the application in an absolute manner.

|

|

|

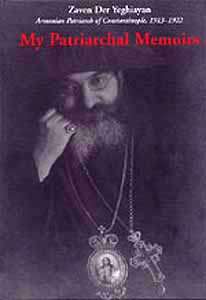

Zaven on cover

of memoirs

|

Not [content] with the tactic which had attracted against them the

animosity of the Turks and had exasperated them, the Armenians, at the end of August 1919,

were on the point of giving to the combined High Commissioners in Constantinople a new

note to draw their attention to the situation of the Christian element in Anatolia and to

the danger that the Armenians of the Republic of Erivan began to seek. Mgr. Zaven, the

Armenian patriarch, in a public statement in Le Temps indicated the direction and the

spirit of it.

|

|

|

|

James

Gerard |

Mr. Gerard, former ambassador from the United States in Berlin, in a

telegram addressed to Mr. Balfour, February 15, 1920, expressed his surprise with

the news where the Allies could not ensure the existence of Armenia and

affirmed that agreements on the division of Armenia had been concluded while Mr.

Balfour was minister of Foreign Affairs, and at one time when the leaders and the

allied statesmen supported their action on the principle of the right of the people

to govern themselves. He declared that 20,000 pastors, 35 evacuees, 250

vice-chancellors of universities and colleges and 40 governors who took part for

[supported] Armenia will not fail to protest against the ruin of Armenia. The

Americans gave 6,000,000 pounds besides to the Armenian aid fund and 6,000,000

pounds are still required of them to help the Armenians for the period of

organization of their State. He recalled that ten members of his party, including

Mr. Hughes and Mr. Root, and with the approval of Senator Lodge, had telegraphed the

President to remind him of the duty that America was to help Armenia. And he added: "We

wish highly that Great Britain seriously holds account of the American public

opinion concerning the Armenian affairs and ask whether it is not possible to defer

the study of the Turkish question after the ratification of the treaty by the

Senate."

Mr. Balfour, in his reply, remarked to Mr. Gerard that the first paragraph of his

telegram contained an error and that he had not concluded any treaty, concerning

Armenia. He declared that he did not understand that 20,000 pastors, 35 evacuees,

250 vice-chancellors of universities and colleges and 40 governors can make England

responsible for the immediate creation of Greater Armenia including Russian Armenia

to the north and extending to the Mediterranean to the south. He added:

"Allow me to point out the facts to you:

1. Great Britain does not have interests in Armenia, except those which are based on

humane reasons. In this respect its position is exactly that of America.

2. I have always asked, all the time that I have had occasion, that the United

States took a part of the load necessary to improve the situation in the territories

which were Turkish before the war, and especially that America accepts a mandate on

Armenia. Events on which Great Britain did not have control prevented the

realization of this idea and by delaying the regulation of peace with Turkey had

very unhappy results.

3. It seems that the ideas that one is done on Armenia contain serious errors. You

make call in your first sentence with the principle of car-provision. You refer in

your first phrases to the principle of auto-dispostion. If one takes it in his

ordinary direction i.e. while conforming to the desire of the majority really living

in a district, it should be remembered that in vast areas of Armenia, the

inhabitants are, in an enormous proportion, Mahommedans, and that if one allowed

them to vote, they would certainly vote against the Armenians. I do not think that

this is a conclusion, but it should not be forgotten. It should not be forgotten

that whoever will want to help Armenia for the period of formation will have, I

fear, to be ready to employ military force. The United Kingdom has the greatest

difficulty in ensure the responsibilities of which it has already taken care. It

cannot add Armenia to it. America, with its vast population and its entire

resources, without new obligations imposed by the war, is placed well better to do

so. She has shown herself to be very liberal towards these oppressed people, but I

well fear that even the most generous liberality, if it is not supported by

political and military help, will not prove completely insufficient to cure the

unhappy consequences of cruelty and the bad Turkish government.

If by reading your telegram, my attitude with regard to this question were badly

understood in America. I will be grateful to you if you want to publish this

letter."

|

| Lord Curzon:

"it should well be recognized that the Armenians during these last weeks, are not

comprised of innocent small lambs, as some think. Actually, they were devoted to a

whole series of wild attacks, where they were bloodthirsty." |

Mr. Gerard answered to Mr. Balfour, February 28, that by referring to the treaties

concluded during the ministry from Mr. Balfour, he had in mind the Sykes-Picot agreements

and, after having said "that Great Britain and France did not have the right to

ask America to help Armenia, before they consent to do justice in Armenia," he

declared "that the confusion which reigns in the question of Armenia since 1878 is

not without relationships to a series of arrangements, quite disposed, probably, in which

Great Britain played the dominating role.

"Our faith in the chivalrous conduct of England and France, and our conviction of the

inopportunity to let the Turkish threat prevail on the will of Western civilization by new

sacrifices of Armenia, encourages us to require of you to put an end to the unfavorable

situation of Armenia by begging you to outline a plan to help it reach its legitimate

claims, holding account that we will want to put up us well our share one day and not

forgetting the absolute necessity to continue the agreement which must exist between our

democracies for our mutual good and that of the world."

|

|

Lord Curzon |

A little later Lord Curzon said to the House of Lords that "it

should well be recognized that the Armenians during these last weeks, are not comprised of

innocent small lambs, as some think. Actually, they were devoted to a whole series of wild

attacks, where they were bloodthirsty." The Times of March 19 made the account of

these atrocities.

At the beginning of February 1920, the British Armenia Committee of London had given to

Mr. Lloyd George a memorandum that consigned, before the final regulation of the Turkish

problem was elaborated, essential claims of Armenia.

In this document the committee recorded with regret the doubt expressed by Lord Curzon, on

December 17, 1919, that the total realization of the Armenian program including the

constitution of Armenia extending from one sea to another, was possible, especially as he

realized that the attitude of the United States did not facilitate the solution of the

Armenian question. After having remembered the declarations of Lord Curzon and Mr. Lloyd

George in the House of Lords as well as the House of Commons, the British Armenia

Committee, without ignoring the difficulty, if the United States declined the load of a

mandate and if no agent could be found, of organizing the political unit of all the

Ottoman provinces having to form part of Armenia in accordance with its project, outlined

a program which, to be described as a minimum, did not comprise of less than the complete

liberation and final release of these provinces from Turkish sovereignty. They stated:

|

|

"An Ottoman suzerainty, even nominal, would be a moral insult, since the

Ottoman government deliberately tried to exterminate the Armenian people. "

It would be an international scandal if the bad precedents of Eastern Roumelie,

Macedonia and Crete were followed in the case of Armenia, on the not very solid

ground of the expedients. The relations of Armenia with the Ottoman Empire must

cease completely, and the territory thus separated must contain all of the old

Ottoman provinces. The Ottoman government of Constantinople, during long years,

maintained the hostility and the civil war among the various

local races, and there exists much evidence showing that this strange and malevolent

drawn aside sovereignty, the races populating these provinces would arrive at living

together in terms of friendship and equality."

The British Armenia Committee required that the Armenian territories which were to

be separated from Turkey be immediately joined together in an Armenian State

independent of and not limited "to the only completely insufficient territories

of the Republic of Erivan", and which would include the old Russian districts

of Erivan and Kars, the zone of the old Ottoman territories containing the towns of

Van, Mush, Erzeroum, Erzindjan, etc. and a port on the Black Sea. This document

affirmed that the surviving Armenians were in rather great number "for,

without losing the hope to do better, strengthening, to consolidate and establish

the fortune of a Armenian State within these limits." [They] added:

"The economic distress which currently prevails in the territory of Erivan

is due to the formidable number of refugees of the provinces bordering the Ottomans

who are camped there for the moment. The inclusion of these territories in the

Armenian State would make easy the whole situation, because it would put these

refugees adequate to turn over to them and to cultivate their grounds. With a

reasonable foreign assistance the surviving force as men of the nation would be

sufficient to establish a national State on this territory, which contains only half

of the Armenian total territory that must be separated from Turkey. In the new

State, the Armenians will be even more numerous than the other non-Armenian

elements, elements which do not have union between them and which were decimated

during the war like the Armenians."

Lastly, in support of its thesis, the committee stressed the threat that the

nationalist movement of Mustapha Kemal posed for England and showed that Armenia

could only avoid danger by coming on this side.

|

| |

"If, indeed, the government of Mustapha Kemal remains upright, our new Kurdish

border will never be quiet; the loads of its defense will constantly be increased, and the

effects of the disorders would be felt to the Indes. If, on the other hand, this hearth of

disorders is replaced by a stable Armenian State, our burden will be surely

decreased."

The British Armenia Committee, summarizing its principal claims, claimed the complete

separation of the Ottoman empire from the Armenian territories, and, in the absence of an

American mandate, the meeting of the Armenian provinces of the Turkish empire bordering on

the Republic of Erivan to the territory of this Republic with a port on the Black Sea.

In the report of the American Commission sent to Armenia, under the direction of General

Harbord, to make there an investigation, and that President Wilson, at the beginning of

April 1920, transmitted to the Senate which had already asked for this communication

twice, no conclusion was reached on whether America were to accept or refuse the mandate concerning this country. The report

declared only that the United States was not to accept a mandate without agreement with

France and Great Britain and without Germany and Russia giving their approval in a formal

way. One found there only enumerated carefully the reasons which can militate for the

acceptance of this mandate and those who were to call against it.

It was declared there first of all that, whatever the power which accepts the mandate,

this one should have under its control the entirety of Anatolia, Constantinople and Turkey

of Europe and to absolutely maintain the foreign relations and the fiscal system of the

Ottoman empire.

The reasons which General Harbord put forward the acceptance of the mandate by the United

States were, after having called upon the humane feelings and to have said the interest

that there was for them to ensure the peace of the world, that was to answer the view of

the people of the Middle East from which all the preferences went to the American

administration, and which in the alternative of a refusal, their choice would preferably

be made upon Great Britain. He made the point that each great power, if he could not

obtain a mandate, prefers that America be in charge.

|

|

The report evaluated the expenditure which would cause the acceptance of the mandate

to 275 million dollars for the first year and to 756,140,000 dollars for the first

five years. At the end of a certain time, the benefit obtained by the power agent

would end up balancing his expenditure and the American capital could find there an

advantageous placement. But the board of directors of the Ottoman debt should be

dissolved and all the commercial treaties concluded by Turkey should be abolished.

The Turkish imperial debt would be unified and a system of refunding should be

established. The economic conditions granted to the elected power would be prone to

revision and should be able to be cancelled.

Moreover, the report pointed out that if America refuses the mandate, the

international competitions which had free course under the Turkish domination were

still going to be prolonged.

The reasons given against acceptance in the American Commission Report were that

serious interior problems held all the attention of the United States and that the

fact of a similar intervention in the businesses of the Old World would weaken the

position which they took from the point of view of the Monroe Doctrine. The report

also pointed out that the United States had by no means contributed to create the

difficult situation which exists in the East and it was one which could not engage

their policy for the future, because the new congress cannot be dependent on the

policy pursued by that which exists today. Great Britain, as well as Russia, claimed

this report, as well as the other great Powers, ignored these areas, but England has

experience and the resources necessary to ensure control of it. The report also

emphasized that the United States has more imperative obligations to follow with

respect to nearer foreign nations and, the interior, than the more pressing

questions to regulate. Of the remainder, the maintenance of law and order in Armenia

would require an army from one hundred to two hundred thousand men. Lastly, great

advances would be initially necessary and it is certain that the reception would be

at the beginning very weak.

In addition, the British Union of the Company of the nations required of the English

government to give instructions to its representatives so that they may support the

proposal of the Supreme Council tending to entrust to the Company of nations the

protection of the independent Armenian State.

According to the content of the peace treaty with Turkey, President Wilson was

invited to fulfill the functions of referee to fix the Armenian borders, regarding

the provinces of Van, Bitlis, Erzeroum and of Trebizond.

Under these conditions the final solution of the Armenian problem is deferred for a

rather long time and it is difficult to envisage how it would be resolved.

|

| |

|

|