|

|

CONSTANTINOPLE : City of the World's

Desire 1453-1924 (New York, 1996)

by

Philip Mansel

|

|

|

| Excerpts: |

P.47: In the sixteenth century ‘heretics’ were burnt alive in London and Berlin,

massacred in Paris, expelled from Vienna. In 1685 Louis XIV expelled all Huguenots from

France; until 1700 appreciative crowds, led by kings and queens of Spain watched heretics

burn alive in the Plaza Mayor of Madrid. The Ottoman Empire, however, gave religious

freedom to Christians and Jews. George of Hungary wrote in the fifteenth century: “The

Turks do not compel anyone to renounce his faith, do not try hard to persuade anyone and

do not have a great opinion of renegades”. In the seventeenth, in the view of the

traveler and writer Monsieur de La Motraye: “There is no country on earth where the

exercise of all sorts of Religions is more free and less subject to being troubled, than

in Turkey”. He knew what he was writing about, since he himself was a Huguenot forced to

leave France after 1685.

|

|

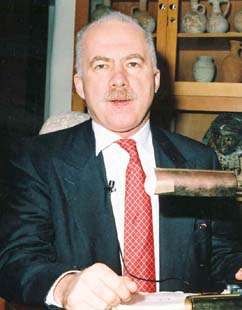

Dr. Philip

Mansel, the author |

P.50: In 1516 the Occumenical Patriarch Thelepus I hinted to the

Tsar that a Russo-Byzantine empire might be created. Clearly, the Patriarch had no

objection to the ‘Christian Emperor of all Christians’ expelling the ‘infidel Turks’.

However, the stage had been set for one of the dramas of nineteenth –and early twentieth

century European history: the Russian drive south to the Black Sea, the Balkans and the

ultimate prize, ‘Russia’s baptismal font’ –Tsarigrad, the city of emperors. The

Patriarch of Constantinople was one of the authors of the drama.

P.51: On 21 March 1657, on the orders of the Grand Vizier, Patriarch

Parthenius III was hanged from a city gate for writing to the Prince of Wallachia saying

that the era of Islam was approaching its end and that soon ‘the lords of the cross and

the bells will be the lords of the empire’. The repeated transformation of churches (in

all forty-two) into mosques asserted the supremacy of Islam.

P.52: As old churches were lost, new ones were built. Without towers

or visible domes, they had to be discreet; even today those built before 1800 are hidden

behind walls and invisible from the street.

P.53: The sight of the mosques and the sound of the muezzin made

Islam visible and audible throughout Constantinople. Beneath the surface of triumphant

Islam, however, was hidden, Christian world of water. The concept of holy water or holy

springs stems from the primeval association of water with life and purification.

P.54: Constantinople is one of the few cities where Muslims as well

as Christians have lived together, over several centuries, in nearly equal proportions. It

is not surprising that the two religions influenced each other. Balikli for example’ was

revered by Muslims as well as Christians. In 1638 Sultan Murad IV is said to have asked

the monks to pray for his victory over Persians. The day they prayed, he took Baghdad. The

crowd, drawn from rich and poor, Muslim and Christian, Bulgarian, Armenian and Catholic,

was sometimes so great that the whole city seemed to be present.

P.55: However’ although hamams and imarets were built beside mosques for Muslim

charitable purposes, Christaians and Jews were permitted to use them. Muslim go to

Armenian churches, Surp Hireshdagaber or Surp Kevorg (St.George) at Balat and even spend

the night there, to cure epileptic children or consult a medium.

P.56: The collective memory and state of mind of the city acquired

an instinctive tolerance, or acceptance, of other religions. The Conqueror’s

calculation, that it was possible to run a multiconfessional capital, proved correct.

Hatred might be expressed in words; it rarely exploded in acts.

|

|

P.334: Artin Pasha Dadian was also a prominent

figure in the Armenian community; he had helped draw up the constitution of 1860,

and in 1871-5 was president of the Armenian National Council.

|

|

Artin

Dadian Pasha |

P.335: In 1896 the Sultan appointed Artin Pasha

Dadian, president of a council to resolve the conflict between the empire and the

Armenian revolutionaries. Having secured and amnesty and liberation of 1.200

political prisoners

he sent his son to Geneva to talk to the exiles. He himself claimed to work for

reforms in the East ‘at once as an Ottoman civil servant and as an Armenian’.

When an Armenian radical smiled at the phrase, he said: ‘I know that you young

Armenians, you do not believe in my patriotism and believe me a Turkish zealot. …

‘it is our duty to work faithfully for the state and fear movements of revolt so

as not to suffer terrible punishments. He ended with a cry from the heart: ‘Prudent

patriotism, is it not also patriotism?’ In a letter of 1898, intended for the

Dashnak party, he is lucid and prophetic: … Fourth, various organizations are

fighting different causes, each in their own way, and in the middle of all this

stands the pitiful Artin Pasha, who on one hand begs the Sultan for mercy by telling

him that this would be the best thing for his empire and on the other hand fights

base individuals who in order to attain their selfish aims are even willing to sell

their nation.

P.337: While some Armenians and Bulgarians

chose violence, most Greeks were too prosperous to fight for ‘the Great Idea’

They felt that while the Ottomans reigned, Greeks, through their banks and commerce,

governed. In the words of one Greek businessman: ‘We lend them the vivacity of our

intelligence and our business skills; they protect us with their strength, like

kindly giants…’

P.339: During a visit to Balmoral in 1896, Tsar

Nicholas II also revealed his ambition that Russia should take ‘the key to her

backdoor’: Constantinople. Lord Salisbury expressed only limited opposition. Four

years later the Tsar’s ministers agreed that seizure of the Bosphorus was Russia’s

‘most important task in the twentieth century – although, given the weakness of

Russia’s finances and the Black Sea fleet, action was not possible. (Russia’s

designs on Constantinople met widespread acceptance. In 1915 the British Prime

Minister, Asquith wrote that Constantinople’s ‘proper destiny’ was to be

Russian)

P.348: However, mullahs, Greek and Armenian

priests and rabbis were photographed side by side, surrounded by Ottoman soldiers,

in commemoration of their successful organization of the elections. Of the deputies

elected in 1908, 142 were Turks, 60 Arabs, 25 Albanians, 23 Greeks, 12 Armenians

(including four Dashnaks and two Henchaks), five Jews, four Bulgarians, three Serbs,

one Vlach. The colloquial term appropriated by followers of the Committee, had about

60 deputies. Others included ulema opposed to secularization, conservatives, and

liberals in favour of decentralization.

P.366: The last military expression of the

concert of Europe which had regulated the Continent since the defeat of of Napoleon

(except during his nephew’s reign) could be seen on the streets of Constantinople

in 1912-13. On 12 November with Ottoman permission, fourteen foreign warships

carrying 2.700 sailors anchored in the Bosphorus to reassure the Christian

population. On 16 November a delegation from the Armenian Patriarchate asked the

embassies for protection. On 18 November, the sailors landed with machine guns. The

French took up position in Galata, the British in Pera, Austrians and Germans in

Taksim, and Russians along the quays.

P.368: The empire’s weakness strengthened the

great powers; anti-Ottoman bias, which had been growing since the 1890s. Before the

war, in the expectation of Ottoman victory, they had issued a declaration against

changes in the status quo in the Balkans. After Ottoman defeats, they helped Balkan

states divide the spoils. Unofficial economic protectorates were marked out, for

Britain in Mesopotamia, for France in Syria, for Russia in northern Anatolia, for

Germany along the Berlin to Baghdad railway. The British ambassador wrote: ‘All

powers including ourselves are trying hard to get what they can out of Turkey. They

all profess to wish maintenance of Turkish integrity but no one ever thinks of this

in practice’. A feeling that the Ottoman Empire was entering its death-agony

permeates private letters as well as diplomatic letters. The ousted Grand Vizier

Kamil Pasha’ rightly known as ‘Ingiliz Kemal’ called for ‘some adequate

foreign control… in regard to the administration of Turkey.

P.370: In August 1914 the British government

lost further popularity by confiscating for its own use two Ottoman battleships

which had been paid for by public subscription in the Ottoman Empire and built in

British yards (the confiscation was not early enough, however, to prevent Enver

using the ships as bait to lure a reluctant Germany in the 2 August alliance).

P.375: The last Allied troops withdrew in

January 1916. During the fighting at Gallipoli, a greater cataclysm was decided in

Constantinople. The Committee had at first enjoyed relatively good relations with

Armenians. Between 1909-1914 both the Armenian national assembly and congresses of

the Hunchak party had met in the capital. An Armenian, Gabriel Noradoungian, a

protégé of Ali Pasha had briefly been Minister of Foreign Affairs in 1912-13 (left

for Paris soon after) In 1914 some Armenians helped Russian troops in Anatolia

against Ottoman forces. There was an Armenian rising in Van. In Constantinople

itself some Armenians were seen gloating over the first Russian victories.

|

| |

P.377: The wartime alliance turned

Constantinople into a magnet for Germans. A German naval base was established at Istinye

on the left bank of the Bosphorus. Workers from Krupps served munitions factories; among

the German officers stationed in Constantinople were Von Papen and Ribbentrop. Enver’s

chief of staff in the War Ministry was the able General Hans von Seeckt, the future

organizer of the German army after 1919.

P.382: In 1919, drunk with victory, the Allies were about to impose

a vindictive peace on the Central Powers, and to remodel Europe on nationalistic lines.

The defeat of the Ottoman Empire was so total that some Allied statesmen hoped to inflict

worse terms on the Ottoman Empire than on Germany, including the loss of Constantinople.

The British Prime Minister Lloyd George was a believer in Mazzinian nationalism,

passionately pro-Greek and an intimate of Sir Basil Zaharoff. In 1918 he had promised that

Constantinople would remain Ottoman; in 1919 he declared ‘Stamboul in the hands of the

Turks has been not only the hot bed of every sort of Eastern vice but it has been the

source from which the poison of corruption and intrigue has spread far and wide into

Europe itself…Constantinople was not Turk and the majority of the population was not

Turkish’. In the disruption that followed the war, statistics were particularly hard to

compile. However, according to an estimate from British officers on the spot, the

population in 1920 consisted of 560,000 Muslims, 206,000 Greeks and 83.000 Armenians. Of

approximately 150,000 foreigners, a large number were Greeks with Hellenic, rather than

Ottoman nationality. Nevertheless, the city had a Muslim, Turkish speaking majority. Above

all, in 1919 more than ever, Turks, Greeks and Armenians each wanted a state of their own,

not a shared city. Curzon’s fixation about this ‘plague spot’ led him into a

militant Christianity which, when governing India, he had rejected. An essay on the

Emperor Justinian had won him a prize at Oxford…

P.393: In order to give the nationalists a ‘knock-out blow’, the

Allies authorized a large scale Greek advance in Anatolia and Thrace. On 8 July the Greek

army took Bursa.On 26 July King Alexander made a triumphant entry into Edirne. For the

next two years, while Greek and Turkish armies fought for Anatolia, with Allied permission

Greece used Constan-tinople as a military and naval base, landing munitions on the quays

of Galata and recruiting soldiers in the street.

P.397: While nationalists left Constantinople to join the army,

waves of refugees and orphans, Turkish, Kurdish and Armenian, poured into the city. There

were so many that they took over military schools, palaces and mosques. A special

American-funded charity called Near East Relief, fed over 160,000 people a day in

Constantinople. Some horrors, however, were spared the city. In 1919 many died in Cairo

and Alexandria during anti-British risings; the Greek occupation of Izmir began with a

massacre of Turks; French forces bombarded Damascus in 1920. Constantinople, however, was

miraculously free of bloodshed, except in March 1920. Turkish memoirs reveal more injured

pride than physical suffering: Turks complained of Greeks’ and Armenians’ ‘intolerable

smiles’ and ‘generally obnoxious’ behaviour on ferries and trams. They were accused

of such crimes as traveling first-class on second-class tickets, or being given seats on

trams by Armenian conductors while Muslims were ejected.

P.398: The city , which had received so many refugees from different

regions, from Spain, Poland and Central Asia, now witnessed the arrival of a procession of

126 boats containing 145,693 Russians (and Russian imperial stud). They came not, as many

Russians had once hoped, to hang ‘Russia’s shield for ever on the gates of Tsarigrad’,

but as refugees traveling in indescribable squalor. Some were so hungry and thirsty that

they lowered their wedding rings on cords, down to boatloads of Greek and Armenian

shopkeepers, in return from bread and water. They slept in the stables of Dolmabahce

palace, or prostitutes’ vacated rooms in the port hotels of Galata.

P.414: The Caliph’s secretary Salih Keramet, son of the poet Nigar

hanim, recorded in his diary that the cars frequently got stuck in mud on the road, and

gendarmerie had to put downs stones to enable to drive free. At 11, tired, hungry and sad,

the party arrived at Catalca railway station. The Caliph tried to smile when the police

and gendarmerie gave him his last salute. The station manager tried to make them

comfortable in his family’s private quarters. He was Jewish and Jews were the only

minority to retain bond of loyalty to the dynasty. When the Caliph expressed his thanks,

the station manager replied in words which brought tears in all eyes:

"The Ottoman dynasty is the

saviour of Turkish Jews. When our ancestors were driven out of Spain, and looked for a

country to take them in, it was the Ottomans who agreed to give us shelter and saved us

from extinction. Through the generosity of their government, once again they received

freedom of religion and language, protection for their women, their possessions and their

lives. Therefore our conscience obliges to serve you as much as we can in your darkest

hour."

|

|

The above comes courtesy of Sukru

S. Aya. The book copy was further identified as: St. Martin’s Press, NY, ISBN 0-312-141574-8

Holdwater adds from the first chapter:

"[The city's] name, in everyday spoken

Turkish, even before the conquest, was a corruption of the Greek phrase for `into

the city', eis teen teen polin: Istanbul."

|

| |

Armenians were another Christian element brought to

Constantinople by the Sultan. They were a distinct nationality which had lived since

at least the sixth century BC in eastern Anatolia and the Caucasus. Since the

Ecclesiastical Council held at Chalcedon — modern Kadikoy — opposite

Constantinople in 451, both Orthodox and Catholics have held the belief that Jesus

Christ is of two distinct natures, human and divine. Armenians, however, are

Monophysites who believe that Jesus Christ has one nature, at once human and divine.

Their use of the Armenian language and alphabet maintained their distinct identity,

despite the disappearance of the last Armenian kingdom in southern Anatolia in the

fourteenth century. They were prominent in the eastern Mediterranean as jewellers,

craftsmen (especially builders) and traders skills which naturally appealed to the

Conqueror. Kritovoulos writes that Mehmed II `transported to the city those of the

Armenians under his rule who were outstanding in point of property, wealth,

technical knowledge and other qualifications and in addition those who were of the

merchant class'. This is the Sultan's smooth official version. An Armenian merchant

called Nerses, writing in 1480, blamed the Sultan for raising `an immense storm upon

the Christians and upon his own people by transporting them from place to place ...

I composed this in times of bitterness, for they brought us from Amasya to

Konstandnupolis by force and against our will; and I copied this tearfully with much

lamentation.'

Armenian tradition, reflected in an inscription on the facade of the present

Armenian patriarchate in the Kumkapi district of Istanbul, asserts that Mehmed II

appointed an Armenian Patriarch in Constantinople in 1461. In reality the Armenian

Patriarch remained in Sis in Cilicia or Echmiadzin in the Caucasus, where he still

is. Such historical myths are a tribute to the Armenians' desire to raise their

position in the Ottoman Empire, and to Mehmed II's reputation as a supranational

hero like Alexander the Great, whom different nationalities could invoke as a

protector. Nevertheless as the Armenians grew in wealth and influence, the status of

their bishop rose. By the seventeenth century he was recognized as an honorary

Patriarch, or `prelate called Patriarch', and administered his own law-courts and

prison like the Qecumenical Patriarch.

The Traditional Viewpoint was offered by

Vahan M. Kurkjian, from "A History of Armenia," (1958):

Muhammed II,

the Fatih (Conqueror), Sultan of the Ottoman or Osmanli Turks, captured

Constantinople by storm in 1453. He treated the Armenians with tolerance and

kindness. He ordered the transfer into his new capital of a large colony of

Armenians and their settlement in six specified quarters within the walls.

These were Kara-Gumruk, Matla, Tcharshamba, Tekké, Keumur Odalar and Akhir

Kapou. Under official designation, they were originally known by the

collective name of Alti-Jemaat (the Six Communities). The Conqueror regarded

the Armenians as a progressive and industrious element, upon whose loyalty he

could fully count. He summoned to the capital Bishop Hovakim, the Prelate of

the Armenians of Brussa, a former Turkish capital, and bestowed upon him the

rank of Patrik (Patriarch), with all the honors and privileges accorded to the

Greek Orthodox Patriarch.

|

|

| |

|

|