|

|

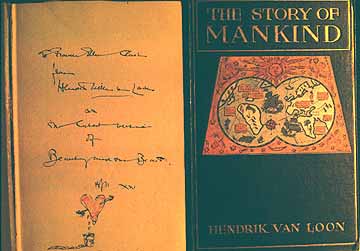

Hendrik Willem van Loon's "The Story of Mankind"

(1921) is a book I remember since I was a child, as it was in my father’s collection. I

ran into the work again, and figured what a grand example it would be of western history

that largely reinforces the racist western attitudes toward the Turks that persist to this

day.

|

|

Hendrik Van Loon signed this copy of

his book for Frances Clarke |

This is a famous work, the first winner of the Newberry Award, in

1922. The author (1882-1944) was born in Rotterdam, arriving in the United States in 1903.

The Dutch-American served as an A.P. war correspondent during Russia’s conflict in 1905

and in 1814 Belgium; he later became a professor of history at Cornell University, and

authored several books including The Story of the Bible (1923) and America (1927), became

known for his informal style.

The book is actually fun to read (available as an e-book on http://www.authorama.com/story-of-mankind-2.html),

in a stylistic sense... and the condensation of all human history into one modest volume

is surely not an easy task. I took a peek at current thoughts regarding the work at

Amazon, and most are pretty ecstatic. Several feel the book should be part of modern

school reading, and one referred to "The Story of Mankind" as "The greatest

history book," in 2002. If that’s how people today feel about a work that has

trouble maintaining objectivity, we can well understand the skewed views in Armenian and

genocide forums that continue to brand the Turks as monsters.

Another reviewer (whose complaint has nothing to do with Turks) gets it more correctly:

“...(Y)ou'll find this book to be like the old adage more ‘His story’ than history.

The writer's personal value system shines through the book as he interprets his view of

history.”

Of course the book is Eurocentric, but at least he gives a fair shake to the “less

important” parts of the world. For example, India and China are covered in one flimsy

volume... but at least they are covered. What does the author have to say about the

Ottoman Empire, which challenged the longevity of the Romans’ empire? It’s as if the

Ottomans never existed... and in the few spots the Turks are mentioned, they are once

again the troublemakers for humanity.

The author explains why he concentrated on some histories at the expense of others in the

following revealing fashion: “Then there were other critics, who accused me of direct

unfairness. Why did I leave out such countries as Ireland and Bulgaria and Siam while I

dragged in such other countries as Holland and Iceland and Switzerland? My answer was that

I did not drag in any countries. They pushed themselves in by main force of circumstances,

and I simply could not keep them out. And in order that my point may be understood, let me

state the basis upon which active membership to this book of history was considered.

There was but one rule. ‘Did the country or the person in question produce a new idea or

perform an original act without which the history of the entire human race would have been

different?’ It was not a question of personal taste. It was a matter of cool, almost

mathematical judgment. No race ever played a more picturesque role in history than the

Mongolians, and no race, from the point of view of achievement or intelligent progress,

was of less value to the rest of mankind.”

By extension, the “Mongol Turks” deserve no less our contempt. Just like the Armenian

and Greek web sites love to tell us, the Turk’s only worth was in knowing how to kill.

Van Loom sneers: “As for Jenghiz Khan, I only recognise his superior ability in the

field of wholesale murder and I did not intend to give him any more publicity than I could

help.”

Certainly, Genghis Khan was no pussycat. More knowledgeable and dispassionate historians,

while acknowledging his cruelty, also give him credit for being a worthy administrator and

lawgiver. But how did the Mongols’ bloody conquests turn out so much less moral than the

bouquets of flowers the civilized Europeans used under their own brutal suppressions of

other races?

For example, the “Norsemen” from Denmark, Norway and Sweden got a chapter or two. “They

would suddenly descend upon a peaceful Frankish or Frisian village... kill all the men and

steal all the women.” The rest of the chapter gives more of the same, and the Norsemen

are sometimes almost glorified with lines such as “the passion of conquest was strong in

the blood of his children.” How is that different than what drove Genghis’ brood?

What was the “new idea or... original act without which the history of the entire human

race would have been different” these descendants of the Vikings offered? Do they

deserve mention because Rollo, a tenth century Viking, was offered the province of

Normandy by the weak king of France, and thereby became “Duke of Normandy”? That is,

did the Norsemen become important because they established little kingdoms in Europe? Didn’t

the Ottoman Turks do the same?

|

|

Alexander the Great gets a whole chapter, albeit a

brief one. The Macedonian performed stunning conquests, bringing death and

destruction from India to Egypt to Persia. A PBS documentary claimed Alexander

punished an island city for refusing to surrender by wiping out every single

inhabitant. (I guess that would be Tyre of 332 BC, where another source reports

great massacres were involved, and the women and children were sold into slavery.) I

wonder if that wouldn’t have earned Genghis Khan’s admiration for “wholesale

murder.” This barbaric act isn’t mentioned in Van Loon’s account, by the way;

instead, he writes: “The (conquered) people must be taught the Greek language —

they must live in cities built after a Greek model. The Alexandrian soldier now

turned school-master. The military camps of yesterday became the peaceful centres of

the newly imported Greek civilisation.” (Maybe that’s why a grateful present day

Iranian featured in the TV documentary said he wished he could wring Alexander’s

neck.) He also tells us with a straight face: “(The Greeks) left behind the

fertile clay of a higher civilisation and Alexander... had performed a most valuable

service.” Hoo-boy!

History is surely a matter of perspective, is it not? Let’s move on to matters of

race, before the treatment of the Turks.

The “heroes” of the human race, the Indo-Europeans, are covered in their own

chapter with the sub-headline

THE INDO-EUROPEAN PERSIANS CONQUER THE SEMITIC AND THE EGYPTIAN WORLD.

“THE world of Egypt and Babylon and Assyria and Phoenicia had existed almost

thirty centuries and the venerable races of the Fertile Valley were getting old and

tired. Their doom was sealed when a new and more energetic race appeared upon the

horizon. We call this race the Indo-European race, because it conquered not only

Europe but also made itself the ruling class in the country which is now known as

British India.” (What is another expression for the “doom” of races... maybe

“wholesale murder”?)

“These Indo-Europeans were white men like the Semites but they spoke a different

language which is regarded as the common ancestor of all European tongues with the

exception of Hungarian and Finnish and the Basque dialects of Northern Spain.”

(The former two is of Ugric origin, a subfamily of the Uralic language group,

closely related to the Altaic group of the Turkish language; the resulting

Ural-Altaic group is also known as Turanian.)

“When we first hear of them, they had been living along the shores of the Caspian

Sea for many centuries. But one day they had packed their tents and they had

wandered forth in search of a new home.” (Just like the Turks.)

“Some of them had moved into the mountains of Central Asia and for many centuries

they had lived among the peaks which surround the plateau of Iran and that is why we

call them Aryans.”

(Why... some of those would be the “Aryan” Armenians, I reckon. You mean they

came from somewhere else, like the Turks? Does that mean Armenia is not the

Armenians’ “ancient homeland,” after all?)

“Others had followed the setting sun and they had taken possession of the plains

of Europe as I shall tell you when I give you the story of Greece and Rome. For the

moment we must follow the Aryans. Under the leadership of Zarathustra (or Zoroaster)

who was their great teacher many of them had left their mountain homes to follow the

swiftly flowing Indus river on its way to the sea.”

The author tells us other Indo-Europeans stuck around western Asia until Cyrus

became king of all Persians, soon mastering western Asia and Egypt. Until they ran

into their Indo-European cousins who had moved to Europe centuries ago, namely, the

Greeks.

Pg. 86: “These “Hellenes, who thousands of years before had left the heart of

Asia and who had in the eleventh century before our era pushed their way into the

rocky peninsula of Greece.”

(WHAT! The Greeks came out of “the heart of Asia”? Just like ... the Turks?)

Pp. 91-93 tells us of the enemies of the early Romans, the Etruscans, and “Our

best guess is that the Etruscans came originally from Asia Minor.” If that would

be western Asia Minor, could that mean there were others who lived there before the

Armenians?

We finally get around to word on Turkic folk, the bad boy Huns, on Pg. 127: “Then

came the fourth century and the terrible visitation of the Huns, those mysterious

Asiatic horsemen who for more than two centuries maintained themselves in Northern

Europe and continued their career of bloodshed until they were defeated near

Chalons-sur-Marne in France in the year 451.”

The author presents a fairly written chapter on “Mohammed,” offering two reasons

for the success of Islam. (“[T]he average Mohammedan carried his religion with him

and never felt himself hemmed in by the restrictions and regulations of an

established church... Of course such an attitude towards life did not encourage the

Faithful to go forth and invent electrical machinery or bother about railroads and

steamship lines. But it gave every Mohammedan a certain amount of contentment. It

bade him be at peace with himself and with the world in which he lived and that was

a very good thing.”

“The second reason which explains the success of the Moslems in their warfare upon

the Christians, had to do with the conduct of those Mohammedan soldiers who went

forth to do battle for the true faith. The Prophet promised that those who fell,

facing the enemy, would go directly to Heaven. This made sudden death in the field

preferable to a long but dreary existence upon this earth. It gave the Mohammedans

an enormous advantage over the Crusaders who were in constant dread of a dark

hereafter, and who stuck to the good things of this world as long as they possibly

could. Incidentally it explains why even to-day Moslem soldiers will charge into the

fire of European machine guns quite indifferent to the fate that awaits them and why

they are such dangerous and persistent enemies.”

(But... isn’t there a concept of “Heaven” in Christianity, as well as “Hell,”

just like in Islam? Maybe the Crusaders were afraid to die because they

subconsciously knew what they were doing — committing “wholesale murder” —

was wrong, and that they weren’t destined for the Pearly Gates.)

|

| |

Up till now, the Turks have been “invisible men” in “The

Story of Mankind.” They suddenly come to light when those heroes of mankind, the

Indo-European tribes, decide to reign terror, death and destruction to the Turks. Here is

the author’s chapter on “The Crusades” (pp. 168-173):

BUT ALL THESE DIFFERENT QUARRELS WERE FORGOTTEN WHEN THE TURKS TOOK THE HOLY LAND,

DESECRATED THE HOLY PLACES AND INTERFERED SERIOUSLY WITH THE TRADE FROM EAST TO WEST.

EUROPE WENT CRUSADING DURING three centuries there had been peace between Christians and

Moslems except in Spain and in the eastern Roman Empire, the two states defending the

gateways of Europe. The Mohammedans having conquered Syria in the seventh century were in

possession of the Holy Land. But they regarded Jesus as a great prophet (though not quite

as great as Mohammed), and they did not interfere with the pilgrims who wished to pray in

the church which Saint Helena, the mother of the Emperor Constantine, had built on the

spot of the Holy Grave. But early in the eleventh century, a Tartar tribe from the wilds

of Asia, called the Seljuks or Turks, became masters of the Mohammedan state in western

Asia and then the period of tolerance came to an end. The Turks took all of Asia Minor

away from the eastern Roman Emperors and they made an end to the trade between east and

west.

(The period of tolerance came to an END! Is that why Armenian historians chronicled how

much better off they were than under their persecuting co-religionists, the Byzantines?)

Alexis, the Emperor, who rarely saw anything of his Christian neighbours of the west,

appealed for help and pointed to the danger which threatened Europe should the Turks take

Constantinople.

The Italian cities which had established colonies along the coast of Asia Minor and

Palestine, in fear for their possessions, reported terrible stories of Turkish atrocities

and Christian suffering. All Europe got excited.

(And thus began the mainly concocted tales of “The Terrible Turk,” which persist to

this very day. Who doubts these “terrible stories” weren’t exaggerated, as the

tellers had the ulterior motive of being “in fear for their possessions,” just like

the Armenians made up their wild tales, equally seeking the intervention of European

powers? The Armenians also were, and still are, fully aware of the built in image problem

of the Turks that makes it so easy to hoodwink biased westerners to swallow these tall

tales.)

Pope Urban II, a Frenchman from Reims, who had been educated at the same famous cloister

of Cluny which had trained Gregory VII, thought that the time had come for action. The

general state of Europe was far from satisfactory. The primitive agricultural methods of

that day (unchanged since Roman times) caused a constant scarcity of food. There was

unemployment and hunger and these are apt to lead to discontent and riots. Western Asia in

older days had fed millions. It was an excellent field for the purpose of immigration.

Therefore at the council of Clermont in France in the year 1095 the Pope arose, described

the terrible horrors which the infidels had inflicted upon the Holy Land, gave a glowing

description of this country which ever since the days of Moses had been overflowing with

milk and honey, and exhorted the knights of France and the people of Europe in general to

leave wife and child and deliver Palestine from the Turks.

(This Pope was just like the Armenians’ fanatical revolutionary leaders, making up

stories with no concern for the welfare of their people. The Frenchman was one fine man of

God.)

A wave of religious hysteria swept across the continent. All reason stopped.

(Just like in W.W.I Britain, America, and even “ally” Germany, once the wild “genocide”

stories were reported on a wholesale basis. Unfortunately, there is still a scarcity of

“reason” today, when it comes to this issue among genocide fanatics. But there’s

hope! The western world finally acknowledged some of their own wrongdoing with the

monstrous Crusades, even though it took... what? Seven, eight or nine centuries?)

|

|

Onward,

Christian Soldiers! |

Men would drop their hammer and saw, walk out of their shop and take

the nearest road to the east to go and kill Turks. Children would leave their homes to

"go to Palestine" and bring the terrible Turks to their knees by the mere appeal

of their youthful zeal and Christian piety. Fully ninety percent of those enthusiasts

never got within sight of the Holy Land. They had no money. They were forced to beg or

steal to keep alive. They became a danger to the safety of the highroads and they were

killed by the angry country people.

The first Crusade, a wild mob of honest Christians, defaulting bankrupts, penniless

noblemen and fugitives from justice, following the lead of half-crazy Peter the Hermit and

Walter- without-a-Cent, began their campaign against the Infidels by murdering all the

Jews whom they met by the way. They got as far as Hungary and then they were all killed.

This experience taught the Church a lesson. Enthusiasm alone would not set the Holy Land

free. Organisation was as necessary as good-will and courage. A year was spent in training

and equipping an army of 200,000 men. They were placed under command of Godfrey of

Bouillon, Robert, duke of Normandy, Robert, count of Flanders, and a number of other

noblemen, all experienced in the art of war.

|

|

In the year 1096 this second crusade started upon

its long voyage. At Constantinople the knights did homage to the Emperor. (For as I

have told you, traditions die hard, and a Roman Emperor, however poor and powerless,

was still held in great respect). Then they crossed into Asia, killed all the

Moslems who fell into their hands, stormed Jerusalem, massacred the Mohammedan

population, and marched to the Holy Sepulchre to give praise and thanks amidst tears

of piety and gratitude. But soon the Turks were strengthened by the arrival of fresh

troops. Then they retook Jerusalem and in turn killed the faithful followers of the

Cross.

During the next two centuries, seven other crusades took place. Gradually the

Crusaders learned the technique of the trip. The land voyage was too tedious and too

dangerous. They preferred to cross the Alps and go to Genoa or Venice where they

took ship for the east. The Genoese and the Venetians made this trans-Mediterranean

passenger service a very profitable business. They charged exorbitant rates, and

when the Crusaders (most of whom had very little money) could not pay the price,

these Italian "profiteers" kindly allowed them to "work their way

across." In return for a fare from Venice to Acre, the Crusader undertook to do

a stated amount of fighting for the owners of his vessel. In this way Venice greatly

increased her territory along the coast of the Adriatic and in Greece, where Athens

became a Venetian colony, and in the islands of Cyprus and Crete and Rhodes.

All this, however, helped little in settling the question of the Holy Land. After

the first enthusiasm had worn off, a short crusading trip became part of the liberal

education of every well-bred young man, and there never was any lack of candidates

for service in Palestine. But the old zeal was gone. The Crusaders, who had begun

their warfare with deep hatred for the Mohammedans and great love for the Christian

people of the eastern Roman Empire and Armenia, suffered a complete change of heart.

They came to despise the Greeks of Byzantium, who cheated them and frequently

betrayed the cause of the Cross, and the Armenians and all the other Levantine

races, and they began to appreciate the virtues of their enemies who proved to be

generous and fair opponents.

(Poor Armenians and Greeks. For their cover to be blown, all they need is a

visitation from their teary-eyed Christian brethren, in order for the latter to

discover who the real heroes and villains of the equation really are.)

(One example of the virtuousness of the Crusaders’ foes was given in the more

biased Crusader account of “Ten Great Events in History” (1887) by James

Johonnot: “The Christians and Moslems no longer looked upon each other as

barbarians, to whom mercy was a crime. Each host entertained the highest admiration

for the bravery and magnanimity of the other, and in their occasional truces met

upon the most friendly terms. When Richard, the lion-hearted king of England, lay in

his tent consumed by a fever, there came into the camp camels laden with snow, sent

by his enemy, the Sultan Saladin, to assuage his disease, the homage of one brave

soldier to another. But, when Richard was returning to England, it was by a

Christian prince that he was treacherously seized and secretly confined.” While no

doubt good gestures occurred from the Crusaders from time to time, I wonder where

there was a memorable example of similar kindness shown toward the Muslims?)

Of course, it would never do to say this openly. But when the Crusader returned

home, he was likely to imitate the manners which he had learned from his heathenish

foe, compared to whom the average western knight was still a good deal of a country

bumpkin. He also brought with him several new food-stuffs, such as peaches and

spinach which he planted in his garden and grew for his own benefit. He gave up the

barbarous custom of wearing a load of heavy armour and appeared in the flowing robes

of silk or cotton which were the traditional habit of the followers of the Prophet

and were originally worn by the Turks. Indeed the Crusades, which had begun as a

punitive expedition against the Heathen, became a course of general instruction in

civilisation for millions of young Europeans.

From a military and political point of view the Crusades were a failure. Jerusalem

and a number of cities were taken and lost. A dozen little kingdoms were established

in Syria and Palestine and Asia Minor, but they were re-conquered by the Turks and

after the year 1244 (when Jerusalem became definitely Turkish) the status of the

Holy Land was the same as it had been before 1095.

But Europe had undergone a great change. The people of the west had been allowed a

glimpse of the light and the sunshine and the beauty of the east. Their dreary

castles no longer satisfied them. They wanted a broader life. Neither Church nor

State could give this to them... They found it in the cities.

|

| |

Hendrik Willem van Loon did not write this chapter

with total bias, to his credit. But note his hypocrisy.

Remember his “rule” as to which episodes of history would make it into his book?

Here it is, again:

“Did the country or the person in question produce a new idea or perform an

original act without which the history of the entire human race would have been

different?"

Obviously, the historian is unqualified to know the Turks’ contributions to

civilization, because he knows little about Turkish history, other than what he has

read in prejudiced western accounts. To his mind, the Turks are like the Mongols and

the Huns, whose only purpose is to wage war, and the only thing they’re good for

is to commit bloodshed and murder. This is the age-old image Turcophobes today don’t

have to work very hard to keep on perpetuating.

This is why he utters nary a peep about the glorious civilization of the Ottoman

Turks, lasting six centuries... the one that anti-Turkish WWI propagandist Arnold

Toynbee later likened as coming closest to Plato’s Republic.

And yet, at the end of his chapter on the Crusades, he gives his reader the distinct

impression that the Turks were much more civilized and knowledgeable human beings

than the barbarous Christians who left house and home with murder on their minds.

Many of these men returned home, clearly wiser and humbler.

Did that not give the hypocritical Hendrik Willem van Loon a clue that the Turks

belonged in “The Story of Mankind” not as those who set back mankind, but as

those who advanced mankind?

The author reinforces the notion that the glorious Indo-European values are what

saved the Russians from the barbarism of Turkish (that is, “Tartar”) influence,

allowing the Russians to enter the family of civilized man... so that they may begin

their campaign of “Death and Exile,” exiling five million Turks/Muslims and

killing another five-and-one-half-million, during their conquests of Ottoman land...

and challenging Hitler with the death and miseries brought upon many millions (Turks

and non-Turks alike) during Soviet times, continuing to the present day.

|

| |

“The Rise of Russia” (pp. 304-07):

Hence Russia received its religion and its alphabet and its first ideas of art and

architecture from the Byzantine monks and as the Byzantine empire (a relic of the eastern

Roman empire) had become very oriental and had lost many of its European traits, the

Russians suffered in consequence.

Politically speaking these new states of the great Russian plains did not fare well. It

was the Norse habit to divide every inheritance equally among all the sons. No sooner had

a small state been founded but it was broken up among eight or nine heirs who in turn left

their territory to an ever increasing number of descendants. It was inevitable that these

small competing states should quarrel among themselves. Anarchy was the order of the day.

And when the red glow of the eastern horizon told the people of the threatened invasion of

a savage Asiatic tribe, the little states were too weak and too divided to render any sort

of defence against this terrible enemy.

It was in the year 1224 that the first great Tartar invasion took place and that the

hordes of Jenghiz Khan, the conqueror of China, Bokhara, Tashkent and Turkestan made their

first appearance in the west. The Slavic armies were beaten near the Kalka river and

Russia was at the mercy of the Mongolians. Just as suddenly as they had come they

disappeared. Thirteen years later, in 1237, however, they returned. In less than five

years they conquered every part of the vast Russian plains. Until the year 1380 when

Dmitry Donskoi, Grand Duke of Moscow, beat them on the plains of Kulikovo, the Tartars

were the masters of the Russian people.

All in all, it took the Russians two centuries to deliver themselves from this yoke. For a

yoke it was and a most offensive and objectionable one. It turned the Slavic peasants into

miserable slaves. No Russian could hope to survive unless he was willing to creep before a

dirty little yellow man who sat in a tent somewhere in the heart of the steppes of

southern Russia and spat at him. It deprived the mass of the people of all feeling of

honour and independence. It made hunger and misery and maltreatment and personal abuse the

normal state of human existence. Until at last the average Russian, were he peasant or

nobleman, went about his business like a neglected dog who has been beaten so often that

his spirit has been broken and he dare not wag his tail without permission.

There was no escape. The horsemen of the Tartar Khan were fast and merciless. The endless

prairie did not give a man a chance to cross into the safe territory of his neighbour. He

must keep quiet and bear what his yellow master decided to inflict upon him or run the

risk of death. Of course, Europe might have interfered. But Europe was engaged upon

business of its own, fighting the quarrels between the Pope and the emperor or suppressing

this or that or the other heresy. And so Europe left the Slav to his fate, and forced him

to work out his own salvation.

The final saviour of Russia was one of the many small states, founded by the early Norse

rulers. It was situated in the heart of the Russian plain. Its capital, Moscow, was upon a

steep hill on the banks of the Moskwa river. This little principality, by dint of pleasing

the Tartar (when it was necessary to please), and opposing him (when it was safe to do

so), had, during the middle of the fourteenth century made itself the leader of a new

national life. It must be remembered that the Tartars were wholly deficient in

constructive political ability. They could only destroy. Their chief aim in conquering new

territories was to obtain revenue. To get this revenue in the form of taxes, it was

necessary to allow certain remnants of the old political organization to continue. Hence

there were many little towns, surviving by the grace of the Great Khan, that they might

act as tax-gatherers and rob their neighbours for the benefit of the Tartar treasury.

The state of Moscow, growing fat at the expense of the surrounding territory, finally

became strong enough to risk open rebellion against its masters, the Tartars. It was

successful and its fame as the leader in the cause of Russian independence made Moscow the

natural centre for all those who still believed in a better future for the Slavic race. In

the year 1453, Constantinople was taken by the Turks. Ten years later, under the rule of

Ivan III, Moscow informed the western world that the Slavic state laid claim to the

worldly and spiritual inheritance of the lost Byzantine Empire, and such traditions of the

Roman empire as had survived in Constantinople. A generation afterwards, under Ivan the

Terrible, the grand dukes of Moscow were strong enough to adopt the title of Caesar, or

Tsar, and to demand recognition by the western powers of Europe.

In the year 1598, with Feodor the First, the old Muscovite dynasty, descendants of the

original Norseman Rurik, came to an end. For the next seven years, a Tartar half-breed, by

the name of Boris Godunow, reigned as Tsar. It was during this period that the future

destiny of the large masses of the Russian people was decided. This Empire was rich in

land but very poor in money. There was no trade and there were no factories. Its few

cities were dirty villages. It was composed of a strong central government and a vast

number of illiterate peasants. This government, a mixture of Slavic, Norse, Byzantine and

Tartar influences, recognised nothing beyond the interest of the state. To defend this

state, it needed an army. To gather the taxes, which were necessary to pay the soldiers,

it needed civil servants. To pay these many officials it needed land. In the vast

wilderness on the east and west there was a sufficient supply of this commodity. But land

without a few labourers to till the fields and tend the cattle, has no value. Therefore

the old nomadic peasants were robbed of one privilege after the other, until finally,

during the first year of the sixteenth century, they were formally made a part of the soil

upon which they lived. The Russian peasants ceased to be free men. They became serfs or

slaves and they remained serfs until the year 1861, when their fate had become so terrible

that they were beginning to die out.

|

|

In the seventeenth

century, this new state with its growing territory which was spreading quickly into

Siberia, had become a force with which the rest of Europe was obliged to reckon. In

1618, after the death of Boris Godunow, the Russian nobles had elected one of their

own number to be Tsar. He was Michael, the son of Feodor, of the Moscow family of

Romanow who lived in a little house just outside the Kremlin.

In the year 1672 his great-grandson, Peter, the son of another Feodor, was born.

When the child was ten years old, his step-sister Sophia took possession of the

Russian throne. The little boy was allowed to spend his days in the suburbs of the

national capital, where the foreigners lived. Surrounded by Scotch barkeepers, Dutch

traders, Swiss apothecaries, Italian barbers, French dancing teachers and German

school-masters, the young prince obtained a first but rather extraordinary

impression of that far-away and mysterious Europe where things were done

differently.

When he was seventeen years old, he suddenly pushed Sister Sophia from the throne.

Peter himself became the ruler of Russia. He was not contented with being the Tsar

of a semi-barbarous and half-Asiatic people. He must be the sovereign head of a

civilised nation. To change Russia overnight from a Byzantine-Tartar state into a

European empire was no small undertaking. It needed strong hands and a capable head.

Peter possessed both. In the year 1698, the great operation of grafting Modern

Europe upon Ancient Russia was performed. The patient did not die. But he never got

over the shock, as the events of the last five years have shown very plainly.

What have we learned? The Russians lived like “miserable slaves” under the

brutal hand of the “dirty little yellow man,” the Mongols... who “could only

destroy.” (Which the historian prefers to identify as Tartar, narrowing the gap

with the “Mongol Turks.”) No doubt the Russians did not have a picnic. Then what

happens? The Russians free themselves from this “Turkish” yoke. Soon afterwards,

what happens to the Russian people? They lived like miserable slaves, under the

brutal hand of the Russians themselves!

How does the author justify this slavery? The Russian who instituted this policy of

serfdom was a “Tartar half-breed.” A-ha! Must have been Boris Goodunov’s

uncivilized Turkish side that was behind such inhumanity. It was only Peter the

Great’s exposure to Indo-European influences, living in the suburbs of the

national capital (and later, when Peter took trips to European cities) where Russia

took the steps to become a great and civilized nation... instead of wallowing as a

semi-barbarous state, populated by half-Asiatic people (which is a shock, since

Russia’s geography is mainly in Asia).

So how come this policy of slavery among the Russian peasantry continues after Peter

succeeds with his reforms and transforms Russia into a civilized nation from the

backward Byzantine-Tartar state it used to be... well after Peter’s death, until

1861? Not to say the Russian people were much freer after that date, if we recall

the roots of “The Ten Days that Shook the World.”

It seems to me the concept of serfdom/slavery was not an unknown concept during the

Middle Ages in the glorious, civilized nations of Europe, either.

I don’t mean to put down the achievements of Peter the Great; he was aptly named,

because he achieved miracles with the transformation of his country in a short

period of time.... sometimes even in the Ataturk mold. However, unlike Ataturk,

Peter did so with the blood of his own people, uncaring for the fate of all the many

who died, constructing cities such as Moscow. And unlike Ataturk, Peter achieved his

nation’s greatness at the expense of his nation’s neighbors... beginning a

policy that would bring untold death, misery and slavery to millions in the coming

centuries.

Russia’s multi-cultural empire could not compare to the toleration demonstrated

under the many different races and nations under the Ottomans. What is Hendrik

Willem van Loon’s definition of “civilization,” anyway?

|

| |

The mostly villainous Turks make token appearances toward the

end of van Loon’s “Story.”

Pgs. 453-455: “For untold centuries the south-eastern corner of Europe had been the

scene of rebellion and bloodshed. During the seventies of the last century the people of

Serbia and Bulgaria and Montenegro and Roumania were once more trying to gain their

freedom and the Turks (with the support of many of the western powers), were trying to

prevent this.” (Here we go. Get ready.)

After a period of particularly atrocious massacres in Bulgaria in the year 1876, the

Russian people lost all patience. The Government was forced to intervene just as President

McKinley was obliged to go to Cuba and stop the shooting-squads of General Weyler in

Havana.

[10,000 Bulgarians died as a result of their insurrection (to the West, these constituted

"massacres") compared with (according to "Death and Exile," McCarthy)

262,000 Muslims who were killed as a result of Bulgarian and Russian action, and a further

half-million brutally expelled... and mum’s the word on them, of course. During the 19th

century the Russians would declare war on the Ottomans at the drop of a hat, and here we

get the idea that the Russians acted out of humanitarian concerns. Just like we get the

idea that the Americans gave two cents to the lives of the Cubans, and weren’t

interested in pursuing their own imperialist ambitions. (For more information on the “forgotten

genocide” of General Weyler, tune

in here.)]

In April of the year 1877 the Russian armies crossed the Danube, stormed the Shipka pass,

and after the capture of Plevna, marched

southward until they reached the gates of Constantinople. Turkey appealed for help to

England. There were many English people who denounced their government when it took the

side of the Sultan. But Disraeli (who had just made Queen Victoria Empress of India and

who loved the picturesque Turks while he hated the Russians who were brutally cruel to the

Jewish people within their frontiers) decided to interfere. Russia was forced to conclude

the peace of San Stefano (1878) and the question of the Balkans was left to a Congress

which convened at Berlin in June and July of the same year.

|

|

Benjamin

Disraeli |

(Note the implication that the motives of the once-Jewish Disraeli

had much to do with his Jewish sympathies. Perhaps that might have been true; however,

Disraeli was a Christian since the age of 13, and his detractors, in a snidely

anti-Semitic way, will always hold Disraeli’s Jewishness over his head... instead of

looking at his patriotism (trying to keep the Russian bear at bay, preserving England’s

interests), and his sense of integrity. Disraeli knew those like rival William Gladstone

were falsely blowing up the Bulgarian atrocities out of proportion for political

purposes... and was Disraeli’s awareness of how unfairly maligned the Turks were derive

from his “love” of the “picturesque Turks”... or the ability to distinguish right

from wrong? Similar to why Admiral Mark Bristol’s even-handedness toward the Turks in

later years... did that derive from a so-called “pro-Turk” attitude? Note the author’s

contempt for the British statesman:)

This famous conference was entirely dominated by the personality of Disraeli. Even

Bismarck feared the clever old man with his well-oiled curly hair and his supreme

arrogance, tempered by a cynical sense of humor and a marvellous gift for flattery. At

Berlin the British prime-minister carefully watched over the fate of his friends the

Turks. Montenegro, Serbia and Roumania were recognised as independent kingdoms. The

principality of Bulgaria was given a semi-independent status under Prince Alexander of

Battenberg, a nephew of Tsar Alexander II. But none of those countries were given the

chance to develop their powers and their resources as they would have been able to do, had

England been less anxious about the fate of the Sultan, whose domains were necessary to

the safety of the British Empire as a bulwark against further Russian aggression.

To make matters worse, the congress allowed Austria to take Bosnia and Herzegovina away

from the Turks to be "administered" as part of the Habsburg domains. It is true

that Austria made an excellent job of it. The neglected provinces were as well managed as

the best of the British colonies, and that is saying a great deal. But they were inhabited

by many Serbians. In older days they had been part of the great Serbian empire of Stephan

Dushan, who early in the fourteenth century had defended western Europe against the

invasions of the Turks and whose capital of Uskub had been a centre of civilisation one

hundred and fifty years before Columbus discovered the new lands of the west. The Serbians

remembered their ancient glory as who would not? They resented the presence of the

Austrians in two provinces, which, so they felt, were theirs by every right of tradition.

And it was in Sarajevo, the capital of Bosnia, that the archduke Ferdinand, heir to the

Austrian throne, was murdered on June 28 of the year 1914. The assassin was a Serbian

student who had acted from purely patriotic motives.

But the blame for this terrible catastrophe which was the immediate, though not the only

cause of the Great World War did not lie with the half-crazy Serbian boy or his Austrian

victim. It must be traced back to the days of the famous Berlin Conference when Europe was

too busy building a material civilisation to care about the aspirations and the dreams of

a forgotten race in a dreary corner of the old Balkan peninsula.

BROTHER! “It is true that Austria made an excellent job of (administering Bosnia and

Herzegovina),” the author tells us. Not according to what I’ve heard. Soon after the

heavy-handed Austrians took over, the people missed the fairness of Ottoman rule. Otherwise, why did this Serbian student

suddenly reach the level of discontent to light the fuse for WWI, when he (or another like

him) could have assassinated an Ottoman official years earlier? After all, it didn’t

take the occupation of the Austrians to make the proud Serbs realize the provinces in

question were theirs by tradition. (Why, during the Yugoslavian break-up just a few years

ago, the Serbs were referring to the Battle of Kosovo from the 14th century as though it

had occurred only “yesterday”!)

|

|

Here is what the author

tells us, as far as historical theory:

When we visit a doctor, we find out before hand whether he is a surgeon or a

diagnostician or a homeopath or a faith healer, for we want to know from what angle

he will look at our complaint. We ought to be as careful in the choice of our

historians as we are in the selection of our physicians. We think, "Oh well,

history is history," and let it go at that. But the writer who was educated in

a strictly Presbyterian household somewhere in the backwoods of Scotland will look

differently upon every question of human relationships from his neighbour who as a

child, was dragged to listen to the brilliant exhortations of Robert Ingersoll, the

enemy of all revealed Devils. In due course of time, both men may forget their early

training and never again visit either church or lecture hall. But the influence of

these impressionable years stays with them and they cannot escape showing it in

whatever they write or say or do.

In the preface to this book, I told you that I should not be an infallible guide and

now that we have almost reached the end, I repeat the warning. I was born and

educated in an atmosphere of the old-fashioned liberalism which had followed the

discoveries of Darwin and the other pioneers of the nineteenth century...

That was very honest of Hendrik Willem van Loon to remind us. The fact that he was

exposed to a liberal upbringing makes me better understand where his negativism

regarding Turks comes from... as it’s the liberal mentality of those such as

William Gladstone to the compassionate do-gooders who are behind organizations like

Amnesty International and genocide institutes who can’t help believing the Turks

are responsible for the worst ills on earth. (And the conservatives hate the Turks

for different reasons, mainly religious.)

As van Loon reminds us, historians are human, and it takes the rare western

historian to shake his deeply-ingrained anti-Turkish belief system, planted there

among those of his western kind, since the days of the Crusades. Unfortunately, it’s

accounts such as this one that persist in solidifying the negative impression among

western audiences, accounts that are still taken as valid and truthful today.

|

| |

|

|