|

|

Please do not quote from the

following English translation!

That's because I attempted a half-derriered

translation, with my poor French and with the aid of Internet translators.

TAT is an English language site, and I

couldn't very well solely present the French version, could I? I think I did

at least a good job in conveying the meaning of the author, even if the style

has been bastardized . But you can check with the original, which is also

provided below.

At any rate, the author is Gilles

Veinstein, and I commend him highly for analyzing the real history of the

Armenians' so-called genocide. I commend him especially because he's French,

and the French are hopelessly brainwashed when it comes to the Armenians.

(Almost as much as my fellow Americans.)

Monsieur Veinstein is a director in

Turkish and Ottoman studies at EHESS, l’École des Hautes Etudes en

Sciences Sociales (The School of High Studies in Social Sciences).

The following appeared in Revue "L'HISTOIRE",

no.187, AVRIL 1995 (History Review, No. 187, April 1995.) Thanks to the nifty

home page of Arlindo Correia, from Portugal, where I got this from.

|

|

|

| THREE

QUESTIONS ABOUT A MASSACRE |

|

|

Gilles

Veinstein at a 2004 Harvard Univ.

conference honoring Prof. Halil Inalcik |

Critical reflections of a specialist in the Ottoman Empire on the

manner in which one wrote the history of the massacre of the Armenians.

There is nothing falser, to begin, than the presupposition that Turks and Armenians would

have been hereditary enemies during the centuries. A people which had known many other

foreign dominations were now under an empire that was multi-denominational and

multi-ethnic. Admittedly this empire was dominated by a Moslem leading class, but the

Christian subjects and Jews profited from the statute of dhimmi ("protected persons

of different faith"). The Armenians were not an exception to this general situation

at all. Any concept of racism was absent in the relations of governing their dhimmi, as

true as if one of them converted to Islam, plus nothing did not distinguish them from the

other Moslems.

Irreducible oppositions will not emerge from there, but they will be of a national nature,

which implies besides that the hostility which will develop then, by nature, will not be

unilateral but reciprocal. Moreover, this antagonism will appear only tardily: whereas the

other Christian people of the empire began to revolt as early as the 17th century, the

Armenians remained during this time for the Ottomans as the "faithful" community

par excellence: they will be the last Christian subjects of the sultan to launch

themselves in the nationalistic struggle, but they will do so at a time, the end of the

1870s, where the loss of the European possessions, following the Treaty of Berlin (1878)

and of its extensions, is already largely advanced and where, consequently, the Asian

territories have more and more the appearance of a last refuge of the power Ottoman.

However it is on a substantial part of this "sanctuary" that the claims of the

young Armenian nationalism carry. And if, at the beginning, the will of independence is

not always expressly acknowledged (one speaks about "reforms" and especially

about autonomy), it is obviously of that which is the matter in the final analysis.

This claim applies to the six vilayets of the Northeast of Asia minor corresponding to the

historical "Greater Armenia,” as with Cilicia or "Lesser Armenia." No

doubt these areas contained many Armenian peasants, present since time immemorial, but

nowhere in Anatolia at this time did the Armenians represent the demographical majority.

They coexisted with the Moslems who were in superior numbers: Turks, Kurds or refugees,

brought by the Russian advances in the Caucasus or the withdrawal of the Ottomans in the

Balkans. And when this national claim was expressed in the form of terrorism, it further

widened the gap between the two communities (1).

|

THE PROOF AND THE TESTIMONY

|

On June 1, 1915, the Ottoman government, which belonged then to the Committee of

Union and Progress (CUP), which came to power by the "Young Turk"

revolution of 1908, ordered the transfer of the Armenians of central and eastern

Anatolia towards Syria, still a possession of the Ottomans at that time. All the

Ottoman-Armenians were not included/understood in the measure: those of Istanbul and

Izmir were excluded, in the same way, of course, as those of Syria. The "Young

Turk" government was then plunged into the First World War; and it was in a

very bad position. The Armenians had formed seven units of Armenian volunteers

alongside the Russian army. In addition, the Armenian populations had risen in

Anatolia, particularly in Van, to the Northeast, and Zeitoun in Cilicia (2).

It is during these transfer operations that an immense number of Armenians perished.

This tragedy was the result of a multiplicity of events which proceeded in various

places in 1915 and 1916, and in which the horror took very diverse forms. The tests,

malnutrition, the conditions of hygiene, the epidemics give an account of part of

the deaths (3), but it is necessary to equally (consider) the massacres which

constituted crimes against humanity. Those were due to intercommunity payments of

account in which it is necessary to announce an active share of the Kurds and not

only of the Turks; with operations of plundering launched against the convoys, but

also with the intrigues of the soldiers charged with the supervision; moreover, it

is undeniable, in certain cases at least, that the crimes were perpetrated with the

open or tacit co-operation of local authorities.

The reality of the massacres, and even their extent, are not questioned by anybody,

including those in Turkey. In fact, the controversy relates to three principal

points, of extremely different nature. Initially, the figure of a million and half

of victims which is reproduced on the memorial of Marseilles, and which is ritually

repeated, are rejected today by many historians, close relations or not of the

official Turkish theses. Far from being the more minimalist, the American

demographer Justin McCarthy, for example, estimates that the whole of the Armenians

of Anatolia did not exceed a million and a half people on the eve of the world-wide

conflict, and that, taking into account the figure of survivors, approximately 600

000 Armenians perished in Anatolia in 1915; that is to say, about half of the

community (4).

Second point: there were also very many victims among the Moslems throughout the

war, because of combat but also of the actions conducted against them by Armenians,

in a context of ethnic and national rivalry (5). If there are forgotten victims,

they are well these, and the Turks of today have the right to denounce the

partiality of the Western opinion in this respect. Is this because they were only

Moslems that they are neglected, or because it would be estimated implicitly that

final success of their fellow beings deprives them of the statute of martyrs? Which

view would we thus relate to with the same facts, if things had turned otherwise, if

the Armenians had finally founded, on the soil of the Ottomans, a durable State in

Anatolia?

But the last point, the crucial one of the debate, by its legal and political

implications, is to know if the massacres perpetrated against the Armenians were on

the orders of the Young Turk government, that is, if the transfers were only a

(cover-up) for a systematic policy of extermination, implemented according to

various methods, but decided, planned, and controlled at the governmental level, or

if the Young Turks were only guilty to have started the displacements imprudently

which finished in tragedy. The sole fact of asking the question can seem absurd and

scandalous. It is true that the official implication is a precondition to the full

application to the Armenian tragedy of the term of genocide, such as it was forged

in 1944 and was defined by the Nuremberg process and the convention of the United

Nations of 1948.

It is necessary nevertheless to admit that one does not so far have proof of this

governmental implication. The documents produced by the Armenians, on the order of

Talaat Pasha, Minister of the Interior, and of other official top ottomans

explicitly ordering the slaughters of men, women, and Armenian children, designated

as the "Andonian documents," after the name of their editor, were only

forgeries, like historical research proved thereafter (6). Undoubtedly the ones in

charge of the martial court indictments were those judging the governing Young Turks

after their fall. In Istanbul in 1919, overwhelming accusations against their

"special formations" of which the Armenians would not have besides been

the only victims among of others, including the Turks themselves. One cannot be

unaware of these precise denunciations, nor to take them either as (money in the

bank), without having regard to the eminently political character of this process:

it was filed against a revolutionary government that had driven the country to

disaster, by its opponents succeeding them in power and ones who were moreover under

the control of the Allies (7). McCarthy talks about two and a half million Muslim

victims (principally Turkish) for the duration of the Anatolian war during 1914 to

1922, of which a million alone came from the zone of the "Armenian vilayet."

For lack of decisive proof, the historians who defend the Armenian theses put

forward several contemporary testimonies, emanating from survivors, diplomats and of

foreign missionaries of various origins. These are far from being negligible and are

even in the better irreplaceable cases. For as much, any rigorous historian knows

the limits of such testimony -- all the more likely to express a point of view “uncommitted"

to a context of generalized conflict (8).

|

| MORE THAN

THOUSAND JUDGMENTS IN MARTIAL COURT |

|

|

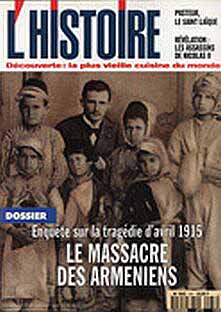

The

publication where this article appeared |

Moreover, whatever the indices which one will estimate to be able to

draw some in favour of an implication of the Ottoman government, it will remain to be

explained how at the same time the authorities of Istanbul denounced the exactions made

against the Armenians, prohibited the renewal of it, led the guilty ones in front of

martial courts. One is informed of 1,397 cases of condemnations of Ottoman agents for

crimes against the Armenians, which included death sentences (9). In the area of Harput in

particular, where terrible violence was committed against the Armenians, according to the

testimony of the American consul Leslie A. Davis, with the agreement of the governor which

affirmed to act on order of the capital (10), 233 lawsuits in martial court were brought

against Ottoman officials accused of crimes against the Armenians, followed by

condemnations (11). The Dutch historian Erik Zürcher proposes an explanation to these

apparent contradictions: while he is nearly convinced of the implication not of the

government but of an internal circle within CUP in the extermination attempt, he notes

nevertheless that it is difficult, if not impossible to prove it "beyond any

doubt" (12).

A historian cannot underline the constant tendency of lawyers of the Armenian cause to

isolate the drama of which they defend the memory of the whole of its historical context,

to disembody it, to make it not what it was - a historic catastrophe with multiple

responsibilities -, but a mythological scene, an attack of the forces of evil against the

forces of good, outside (the reality) of time and space. This outline is received as such,

without critical spirit, by the majority of our fellow citizens, including those in the

media and the political community, often dispensing with thousand miles of realities

historical and geographical, undoubtedly rather complicated and remote. Being grafted on

ignorance and secular prejudices, this outline is generated from an authentic anti-Turkish

racism, as inadmissible (should it be specified?) as all other racism.

Gilles VEINSTEIN, Director of Studies at the EHESS and historian, he devoted (himself to)

many books and articles to the old history of the Ottoman Empire (15th-18th century). In

particular “State and Society in the Ottoman Empire” (London, Variorum, 1994).

|

NOTES:

|

(1) The denouncing of the responsibilities of the leaders sometimes was done by

Armenians themselves, as Arshag Tchobanian in "Badaskhanaduoutiunnere" (“Responsibilities"),

in Anahid, 1, n°3, January 1899.

(2) Here is how the head of the Armenian national delegation, Boghos Nubar,

presented the Armenian participation to the war at the peace conference in Versailles,

in 1919: "since the beginning of the war (he said) the Armenians fought by the

side of the Allies on all fronts. (...) The Armenians have been belligerents de facto,

since they indignantly refused to side with Turkey..." (The Times of London,

January 30 1919, p.10).

(3) All the population movements achieved under the conditions of Anatolia in

war showed a very heavy assessment, even in the absence of any hostile intention: in

the case for example of the retirement of Maras during the winter of 1920, where the

French troops were accompanied by 5 000 Armenians, 2 to 3 000 of the latter perished

on the way; cf George Boudière, "Notes on the Countryside of Syria-Cilicie. The

Matter of Maras (January-February 1920)", Turcica IX/2-X, 1978, p.160.

(4) Justin McCarthy, Muslim and Minorities: the Population of Ottoman Anatolia

and the End of the Empire, NYU Press, 1983. The same author wrote a significant

article: "The Anatolian Armenians, 1912-1922" Armenians in the Ottoman

Empire and Modern Turkey (1912-1926), Bosphorus University, Istanbul, 1984.

(5) Kara Schemsi, Turcs et Arméniens devant l'histoire, Geneva, 1919;

documents relating to the atrocities committed by the Armenians upon the Moslem

populations, Constantinople, 1919; Mayéwski General, The Massacres of Armenia,

Saint-Petersburg, 1916; Christopher Walker, Armenia, the Survival of a Nation, London,

1981; while being resolutely pro-Armenian, this work is very revealing on the

importance of the Moslem victims.

(6) Sinasi Orel and Sureyya Yüca, The Talât Pasha Telegrams : Historical

Facts or Armenian Fiction ?, London, 1986 ; Türkkaya Ataöv, The Andonian

"Documents" Atrributed to Talat Pasha are Forgeries, Ankara, 1984.

(7) To a high extent, the Armenian translation (published by Haigazn K Kazarian)

of the Ottoman text of this indictment is highly tendentious, in several places.

Another trial was organized two years later in Malta by the English against some 150

political prisoners and military Ottomans, but it ended in a withdrawal of the case. (Holdwater note: K[h]azarian was the Armenian appointed by the

British to be in charge of the Ottoman archives, as soon as the British occupied

Istanbul at war's end.)

(8) One showed thus how much a testimony, very often called upon and presented

like "neutral," was suitable for a "criticism of passably instructive

source": Heath W Lowry, The Story Behind Ambassador Morgenthau's Story, The Isis

Press, Istanbul 1990.

(9) Kamuran Gürün, The Armenian File, Triangle, 1984; this aspect of the

official Ottoman attitude, supported by many new documents unpublished of the most

explicit ones, is a major contribution of this book which one cannot elude for the

single reason that it would be about a "semi-official" Turkish publication.

(10) La Province de la Mort, Paris (“The Slaughterhouse Province”), Paris,

1994.

(11) The editors of the memoirs of this consul recently translated into French,

take care not to announce this aspect which the Ottoman files reveal. It is true that,

generally, the systematic partiality in the choice of the sources suffers

unfortunately little from exceptions in the Armenian historians, still much less than

the Turkish historians, as some testify, for example, the collection of studies

referred to above published by the university from the Bosphorus, in Istanbul.

(12) Erik J Zürcher, Turkey. At modern history, New York, 1993.

|

| THE ORIGINAL FRENCH VERSION |

TROIS QUESTIONS SUR UN

MASSACRE

Les réflexions critiques d'un spécialiste de l'Empire ottoman sur

la façon dont on a écrit l'histoire du massacre des Arméniens.

Rien de plus faux, pour commencer, que ce présupposé tenace selon lequel Turcs et

Arméniens auraient été des ennemis héréditaires au cours des siècles. Le

passage sous domination ottomane d'une partie d'un peuple qui avait connu bien

d'autres dominations étrangères avait signifié l'insertion dans un empire

pluriconfessionnel et pluriethnique. Certes cet empire était dominé par une classe

dirigeante musulmane d'ailleurs très cosmopolite, mais les sujets chrétiens et

juifs y bénéficiaient du statut de dhimmi ("infidèles protégés"). Les

Arméniens ne firent aucunement exception à cette situation générale. Toute

notion de racisme était absente dans les relations des gouvernants avec leurs

dhimmi, tant il est vrai que si l'un d'eux se convertissait à I'islam, plus rien ne

le distinguait des autres musulmans.

Des oppositions irréductibles n'en surgiront pas moins, mais elles seront d'ordre

national, ce qui implique d'ailleurs que l'hostilité qui se développera alors, par

nature, ne sera pas unilatérale mais réciproque. Au demeurant, cet antagonisme ne

se manifestera que tardivement : alors que les autres peuples chrétiens de l'empire

commencent à se révolter dès le XVIIème siècle, les Arméniens restent pendant

ce temps pour les Ottomans la communauté "fidèle" par excellence : ils

seront les derniers sujets chrétiens du sultan à se lancer dans la lutte nationale,

mais ils le feront à un moment, la fin des années 1870, où la perte des

possessions européennes, à la suite du traité de Berlin (1878) et de ses

prolongements, est déjà largement avancée et où, par conséquent, les

territoires asiatiques font de plus en plus figure de dernier refuge de la puissance

ottomane. Or c'est sur une partie substantielle de ce "sanctuaire" que

portent les revendications du jeune nationalisme arménien. Et si, au départ, la

volonté d'indépendance n'est pas toujours expressément avouée (on parle de

"réformes" et surtout d'autonomie), c'est évidemment de cela qu'il

s'agit en fin de compte.

Cette revendication s'applique aux six vilayet du Nord-Est de l'Asie mineure

correspondant à la "Grande Arménie" historique, ainsi qu'à la Cilicie

ou "Petite Arménie". Sans doute ces régions conservent-elles de nombreux

paysans Arméniens, présents de temps immémorial, mais nulle part dans l'Anatolie

de cette époque, les Arméniens ne sont restés démographiquement majoritaires.

IIs coexistent avec des musulmans en nombre supérieur : Turcs, Kurdes ou réfugiés,

amenés par l'avance russe dans le Caucase ou le retrait ottoman dans les Balkans.

Et lorsque cette revendication nationale s'exprima sous la forme du terrorisme, elle

creusa le fossé entre les deux communautés (1).

|

| LA PREUVE ET

LE TEMOIGNAGE |

Le 1er juin 1915, le gouvernement ottoman, qui relevait alors du Comité

Union et Progrès (CUP), porté au pouvoir par la révolution "jeune-turque" de

1908, ordonna le transfert des Arméniens d'Anatolie centrale et orientale vers la Syrie,

encore possession ottomane à cette époque. Tous les Arméniens ottomans n'étaient pas

compris dans la mesure : ceux d'Istanbul et d'Izmir en étaient exclus, de même, bien

entendu, que ceux de Syrie. Le gouvernement "jeune-turc" était alors plongé

dans la Première Guerre mondiale ; et il se trouvait en très mauvaise posture. Les

Arméniens avaient formé sept unités de volontaires Arméniens aux côtés de l'armée

russe. En outre, des populations arméniennes s'étaient soulevées en Anatolie, notamment

à Van, au Nord-Est, et à Zeïtoun en Cilicie (2).

C'est au cours de ces opérations de transfert que périrent un nombre immense

d'Arméniens. Cette tragédie fut la résultante d'une multiplicité d'événements qui se

déroulèrent dans différents lieux en 1915 et 1916, et dans lesquels l'horreur prit des

formes très diverses. Les épreuves, la malnutrition, les conditions d'hygiène, les

épidémies rendent compte d'une partie des décès (3), mais il faut faire également

leur part aux massacres qui constituent des crimes contre l'humanité caractérisés.

Ceux-ci étaient dus à des règlements de compte intercommunautaires dans lesquels il

faut signaler une part active des Kurdes et pas seulement des Turcs ; à des opérations

de pillage lancées contre les convois, mais aussi aux agissements des militaires chargés

de l'encadrement ; en outre, il est incontestable, dans certains cas au moins, que les

crimes étaient perpétrés avec la coopération ouverte ou tacite des autorités locales.

La réalité des massacres, et même leur ampleur ne sont mis en question par personne, y

compris en Turquie. En fait, la controverse porte sur trois points principaux, de nature

fort différente. En premier lieu, le chiffre d'un million et demi de victimes qui figure

sur le monument commémoratif de Marseille, et qui est rituellement répété, est

aujourd'hui rejeté par de nombreux historiens, proches ou non des thèses officielles

turques. Loin d'être le plus minimaliste, le démographe américain Justin McCarthy, par

exemple, estime que l'ensemble des Arméniens d'Anatolie ne dépassait pas un million et

demi de personnes à la veille du conflit mondial, et que, compte tenu du chiffre des

rescapés, environ 600 000 Arméniens auraient péri en Anatolie en 1915, soit près de la

moitié de la communauté (4).

Deuxième point : il y eut aussi de très nombreuses victimes parmi les musulmans tout au

long de la guerre, du fait des combats mais aussi des actions menées contre eux par des

Arméniens, dans un contexte de rivalité ethnique et nationale (5). S'il y a des victimes

oubliées, ce sont bien celles-là, et les Turcs d'aujourd'hui sont en droit de dénoncer

la partialité de l'opinion occidentale à cet égard. Est-ce parce qu'il ne s'agissait

que de musulmans qu'on les néglige, ou bien parce qu'on estimerait implicitement que le

succès final de leurs congénères les prive du statut de martyrs ? Quel regard

porterions-nous donc sur les mêmes faits, si les choses avaient tourné autrement, si les

Arméniens avaient finalement fondé, sur les décombres ottomanes, un Etat durable en

Anatolie ?

Mais le dernier point, crucial, du débat, par ses implications juridiques et politiques,

est de savoir si les massacres perpétrés contre les Arméniens le furent sur ordre du

gouvernement jeune-turc, si les transferts n'ont été qu'un leurre pour une entreprise

systématique d'extermination, mise en oeuvre selon des modalités diverses, mais

décidée, planifiée, téléguidée au niveau gouvernemental, ou si les Jeunes-Turcs

furent seulement coupables d'avoir imprudemment déclenché des déplacements qui finirent

en hécatombes. Le seul fait de poser la question peut sembler absurde et scandaleux. Il

est vrai que l'implication étatique est un préalable à la pleine application à la

tragédie arménienne du terme de génocide, tel qu'il a été forgé en 1944 et défini

par le procès de Nuremberg et la convention des Nations Unies de 1948.

Il faut pourtant admettre qu'on ne dispose pas jusqu'à présent de preuve de cette

implication gouvernementale. Les documents produits par les Arméniens, des ordres de

Talaat Pacha, ministre de l'Intérieur, et d'autres hauts officiels ottomans ordonnant

explicitement le massacre des hommes, des femmes, et des enfants arméniens, désignés

comme "documents Andonian", du nom de leur éditeur, n'étaient que des faux,

comme la critique historique l'a prouvé par la suite (6). Sans doute trouve-t-on dans le

réquisitoire de la cour martiale chargée de juger les gouvernants jeunes-turcs après

leur chute, à Istanbul en 1919, des accusations accablantes contre leurs "formations

spéciales" dont les Arméniens n'auraient d'ailleurs été que des victimes parmi

d'autres, y compris chez les Turcs eux-mêmes. On ne peut ignorer ces dénonciations

précises, ni les prendre non plus comme argent comptant, eu égard au caractère

éminemment politique de ce procès : il était intenté contre un gouvernement

révolutionnaire qui avait conduit le pays au désastre, par ses adversaires lui

succédant au pouvoir et, qui plus est, sous la coupe des Alliés (7). McCarthy parle de

deux millions et demi de victimes musulmanes (principalement turques) pour l'ensemble de

la guerre en Anatolie de 1914 à 1922, dont un million pour la seule zone des "vilayet

arméniens".

Faute de preuve décisive, les historiens défenseurs des thèses arméniennes mettent en

avant plusieurs témoignages contemporains, émanant de rescapés, de diplomates et de

missionnaires étrangers de diverses origines. Ceux-ci sont loin d'être négligeables et

sont même dans les meilleurs cas irremplaçables. Pour autant, tout historien rigoureux

connaît les limites d'un témoignage - d'autant plus susceptible d'exprimer un point de

vue ''engagé" dans un contexte de conflit généralisé (8).

|

PLUS DE MILLE

CONDAMNATIONS EN COUR MARTIALE

|

Au demeurant, quels que soient les indices qu'on estimera pouvoir en

tirer en faveur d'une implication du gouvernement ottoman, il restera à expliquer

comment dans le même temps les autorités d'Istanbul dénonçaient les exactions

commises contre les Arméniens, en interdisaient le renouvellement, traînaient les

coupables devant des cours martiales. On a ainsi connaissance de 1 397 cas de

condamnations d'agents ottomans pour crimes contre les Arméniens, dont des

condamnations à mort (9). Dans la région de Harput en particulier, où de

terribles violences contre les Arméniens étaient commises, selon le témoignage du

consul américain Leslie A. Davis, avec l'accord du gouverneur qui affirmait agir

sur ordre de la capitale (10), 233 procès en cour martiale furent intentés contre

des officiels ottomans accusés de crimes contre les Arméniens, suivis de

condamnations (11). L'historien hollandais Erik Zürcher propose pour sa part une

explication à ces apparentes contradictions : s'il est intimement convaincu de

l'implication non du gouvernement mais d'un cercle interne au sein du CUP dans

l'extermination, il constate néanmoins qu'il est difficile, sinon impossible de le

prouver "au-delà de tout doute" (12).

Un historien ne peut que souligner la tendance constante des avocats de la cause

arménienne à isoler le drame dont ils défendent la mémoire de l'ensemble de son

contexte historique, à le désincarner, pour en faire, non ce qu'il fut - une

catastrophe historique relevant de responsabilités multiples - , mais une scène

mythologique, un assaut des forces du mal contre les forces du bien, hors de tout

temps et de tout espace. Ce schéma est reçu tel quel, sans esprit critique, par la

plupart de nos concitoyens, y compris dans les médias et la classe politique,

souvent à mille lieues des réalités historiques et géographiques, assurément

assez compliquées et lointaines, dont il a été coupé. Se greffant sur des

ignorances et des préjugés séculaires, ce schéma est générateur d'un

authentique racisme antiturc, aussi inadmissible (faut-il le préciser?) que tout

autre racisme.

Gilles VEINSTEIN

Directeur d'études à l'EHESS et historien, il a consacré de nombreux livres et

articles à l'histoire ancienne de l'Empire ottoman (XVème-XVIIIème siècle).

Notamment Etat et société dans l'Empire ottoman (Londres, Variorum, 1994).

|

| NOTES : |

(1) La dénonciation des responsabilités des meneurs fut parfois le fait des

Arméniens eux-mêmes, comme Arshag Tchobanian dans "Badaskhanaduoutiunnere"

("responsabilités"), dans Anahid, 1, n°3, janvier 1899.

(2) Voici comment le chef de la délégation nationale arménienne, Boghos Nubar, présenta

à la conférence de la paix à Versailles, en 1919, la participation arménienne à la

guerre : "depuis le début de la guerre, disait-il, les Arméniens ont combattu aux

côtés des alliés sur tous les fronts. (...) Les Arméniens ont été des belligérants de

facto, puisqu'ils ont refusé avec indignation de se mettre du côté de la Turquie..."

(The Times of London, 30 janvier 1919, p.10).

(3) Tous les déplacements de population accomplis dans les conditions de l'Anatolie en

guerre se soldèrent par un très lourd bilan, même en l'absence de toute intention hostile

: dans le cas par exemple de la retraite de Maras de l'hiver 1920, où les troupes

françaises étaient accompagnées de 5 000 Arméniens, 2 à 3 000 de ces derniers périrent

en route ; cf Georges Boudière, "Notes sur la campagne de Syrie-Cilicie. L'affaire de

Maras (janvier-février 1920)", Turcica IX/2-X, 1978, p.160.

(4) Justin McCarthy, Muslim and Minorities : the Population of Ottoman Anatolia and the End

of the Empire, NYU Press, 1983. Le même a écrit un article important : "The Anatolian

Armenians, 1912-1922" dans Armenians in the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey

(1912-1926), Université du Bosphore, Istanbul, 1984.

(5) Kara Schemsi, Turcs et Arméniens devant l'histoire, Genève, 1919 ; documents relatifs

aux atrocités commises par les Arméniens sur les populations musulmanes, Constantinople,

1919 ; Général Mayéwski, Les Massacres d'Arménie, Saint-Pétersbourg, 1916 ; Christopher

Walker, Armenia, the survival of a nation, Londres, 1981, tout en étant résolument

proarménien, cet ouvrage est très révélateur sur l'importance des victimes musulmanes.

(6) Sinasi Orel et Sureyya Yüca, The Talât Pasha Telegrams : Historical Facts or Armenian

Fiction ?, Londres, 1986 ; Türkkaya Ataöv, The Andonian "Documents" atrributed

to Talat Pasha are Forgeries, Ankara, 1984.

(7) Au surplus, la traduction arménienne (publiée par Haigazn K. Kazarian) du texte

ottoman de ce réquisitoire est hautement tendancieuse, en plusieurs endroits. Un autre

procès fut organisé deux ans plus tard à Malte par les Anglais contre quelque 150

prisonniers politiques et militaires ottomans, mais il se termina par un non-lieu.

(8) On a montré ainsi combien un témoignage, très souvent invoqué et présenté comme

"neutre", était susceptible d'une "critique de source" passablement

instructive : Heath W. Lowry, Les Dessous des Mémoires de l'ambasseur Morgenthau, Isis,

Istanbul, 1990.

(9) Kamuran Gürün, Le Dossier arménien, Triangle, 1984 ; cet aspect de l'attitude

officielle ottomane, étayée sur de nombreux documents ottomans inédits des plus

explicites, est une contribution majeure de ce livre qu'on ne peut éluder pour l'unique

raison qu'il s'agirait d'une publication "officieuse" turque.

(10) La Province de la mort, Paris, 1994.

(11) Les éditeurs des mémoires de ce consul récemment traduits en français, se gardent

bien de signaler cet aspect que révèlent les archives ottomanes. Il est vrai que, d'une

manière générale, la partialité systématique dans le choix des sources souffre

malheureusement peu d'exceptions chez les historiens arméniens, encore bien moins que les

historiens turcs, comme en témoigne, par exemple, le recueil d'études cité plus haut

publié par l'université du Bosphore à Istanbul.

(12) Erik J. Zürcher, Turkey. A modern history, New York, 1993.

|

Armenian

Aggression Targets Gilles Veinstein

|

After preparing the above, I did a little surfing

to find out more about Gilles Veinstein. I discovered tetedeturc.com, the

Turkish-French site, had already devoted a page to the courageous historian, which may

be accessed here. It turns out — unsurprisingly — that M.

Veinstein got into hot water because of the above article, thanks to France's huge

contingent of genocide-obsessed Armenians. I'll provide only the battered English

translations of some letters that appeared.

The site tells us:

In an article published by the review History

(a reference in the field of historical research), in his edition of April 1995

(n°187), Mr. Gilles Veinstein, eminent French turcologist in 1999 with the

prestigious College of France, estimated that the use of the term "genocide"

to qualify the massacres of the Armenians during the black years 1915-1916, was not

relevant insofar as the premeditation and the planning of these massacres by the

Ottoman authorities were not established by historical research. However, to have

delivered his opinion of history, Gilles Veinstein was the subject of the worst

calumnies, sudden wretched attacks, victim of pressures, threats, and physical

violence, on behalf of fanatics, in particular Armenian, alive in France; of aucuns

were until calling into question its election to the College of France. The

turcologist, who is of Jewish origin, was even described as a "negationnist"

(sic)! It is advisable here to recall that Gilles Veinstein is a historian of

reputation, a specialist in the Ottoman Empire, whose quality and serious body of work

achieve the unanimity among his peers. His election with the College of France is a

bright confirmation besides. It should be specified that at no time did Gilles

Veinstein deny the massacres of the Armenians during 1915-1916 (moreover, Turkish

historians do not deny them either, but dispute the estimate of the number of the

victims carried out by the Armenian part). He challenges, on the other hand, their

genocide character, which implies that there was a premeditation on behalf of the

authorities Ottomans.

Vis-a-vis these attacks all the same, voices

rose to take the defense of the historian. Thus, in an article of Nicolas Weill,

published in the World of January 27, 1999, we learn that "(...) the researchers

in Social sciences, to start with two consulted turcologists, Louis Bazin and Robert

Mantran, as well as the orientalist Maxime Rodinson, on the other hand lined up as

regards Gilles Veinstein." However, Messrs Bazin and Mantran are nothing less

than the two éminences grise Turcologie Frenchwoman, and Mr. Rodinson, a great French

orientalist. In the same way, Pierre Chuvin, member of the Editorial board of the

review History and professor in Paris X-Nanterre, also gave to him his support for

Gilles Veinstein in an article entitled "Bad lawsuit against a historian,"

published in the January 6, 1999 edition of the Libération newspaper. The great

French historian Pierre Vidal-Naquet, who is a director of studies at the School of

the high studies in social sciences (Ehess), also took the feather in the World, in an

article entitled "On the imaginary negationnism of Gilles Veinstein", to

defend celebrates it professor. Lastly, Alain-Gerard Slama defends the turcologist in

an article entitled "history taken as a hostage," in the Barber of February

1, 1999.

See also "the aggressions of Aix in

Provence" and "Intimidation in Academia"

The site reproduces three letters appearing in

response to Veinstein's piece. The first (Dec. 28, 1998) is by what appears to

be a "genocide scholar," Catherine Coquio. She blasts Veinstein, saying his

views are opposed by many historians, both from France and from outside the country.

(As examples, she actually cites extreme partisans R. Smith, R. Melson, and Israel

Charny.) She goes on with the usual blather, like "the decomposition of hundreds

of thousands stripped bodies, starved, torture victims, under the sun of the

desert..." (where ARE all of these skeletons?), and mentions the offenses of

Bernard Lewis. We've heard it all before, but this time it's in French.

Next, Michel Cahen takes a crack in a letter

appearing three days later. He accuses Coquio of radicalism, weakening the fight

against denialism (or I guess as the French call it, negationism.) However, he

announces his dissent with Veinstein's views, as well as those of Bernard Lewis. The

Armenians suffered genocide, as well as the Tutsis and others, and the list can be

lengthened.

"Thus can one undoubtedly discuss the

nature of the bombardments of Israeli aviation countering Lebanese villages or the

whole of Palestine, in 'punishment category' of a terrorist attack made the

previous day, and I am not sure that the Institute of Research on the Holocaust

and the Genocide of the State of Israel is placed best, as C. Coquio proposes, to

discuss this kind of business. But any war crime is not a crime against humanity, any

crime against humanity is not a genocide and the concept of holocaust must certainly

be even more restrictive." Well, that's an interesting tack.

He declares that contrary to Veinstein's

conclusions, the Ottomans assaulted the Armenians systematically, and that he was

"delighted" when the French National Assembly declared the Armenian

experience as a genocide. But then he faults Coquio for failing to make the

distinction between malicious deniers and those like Veinstein who discuss the nature

of what went on. "To pose Faurisson=Veinstein equations everywhere, it weakens

the fight against the negationnism, a pathology which leads always and very quickly to

the extreme right-hand side."

Prof. Pierre Chuvin next enters the fray with a

Jan. 6, 1999 letter. He defends Veinstein, writing that after Veinstein wrote about

this subject once and only one time, his detractors spoke in the plural "about

the writings" of Mr. Veinstein. Further, he writes:

Is that enough to make of Mr. Veinstein the

denier of the Armenian genocide? The cause should not have to be pled: it is enough to

read his contribution to see that it contains neither negation of the drama nor called

into question of its width. However, he is the object of a violent denigration

campaign, founded very little on what is said and especially on the intentions that

one lends to him: here he is suspected "to be sprinkled subsidies" by the

Turkish government, by Mrs Coquio...

That Bernard Lewis was condemned does

not imply that Gilles Veinstein is condemnable, and of the remainder Madeleine

Rebérioux, president of honor of the League of the humans right, had protested

against this judgment of a historian by a court (History, October 1995, p. 98).

The professor is unafraid to sock it to Mrs. Coquio, even though he, too, is a

supporter of the genocide viewpoint. That's something; it's rare to encounter a biting

criticism of the dogma of genocide scholars in the United States.

|

| |

|

|