|

|

The following is excerpted from

the excellent book, "Ordered to Die: A History of the Ottoman Army in

the First World War," by Edward J. Erickson (Greenwood Press,

Westport, Conn., 2001, pp: 95-104).

Followed by a review.

|

|

|

| |

There

is a huge body of historical literature concerning the "Armenian genocide" that

maintains that the Young Turks, in particular Enver, Talat, and Cemal, intentionally

sought to exterminate the Armenian citizens of the Ottoman Empire. This case against the

Young Turks rests on the premise that they intended to racially purify the empire by

purging or exterminating its minorities, particularly the troublesome Christian Armenians.

Moreover, the literature maintains that under the pretext of wartime emergencies and

threats to national security, the Young Turks took advantage of circumstances to conduct

genocide against the Armenians. Using a combination of methods ranging from massacre to

starvation, the Young Turks then deliberately and intentionally caused the deaths of

several million Armenians. Much of this literature is emotionally charged and a large

percentage of it is directly generated by the descendants of the survivors of the events.

The genocide itself has, over the past eighty years, become a highly political issue in

most western countries, as Armenian descendants seek legislative condemnation of the

modern Turkish Republic. Because of this transgenerational campaign to establish that an

Ottoman genocide (defined as an intentional and systematic attempt to exterminate a people

or a race) against its Armenian subjects occurred, balanced and objective discourse on

this subject becomes difficult.

In many quarters of academia, debate has more or less settled on the acknowledgment that

the genocide occurred as a matter of historical fact. Without question, a large number of

innocent Armenians, including women and children, died during the First World War at the

hands of the Turks. Documentation on this point is incontrovertible and was witnessed by

too many neutral observers, many of whom wrote reliable and immediate narratives and

reports. Because of this, the Young Turks have been intellectually equated with Adolf

Hitler and the Holocaust, and secondarily, the Turkish Army with the German SS. The

Turkish position on the matter is that the Armenians were actively engaged in terrorism

and in outright insurrection beginning in April 1915. Military necessity therefore

justified the deportation of the Armenians. Both sides conducted unsanctioned massacres,

but to this day the Turks deny that the Ottoman government sought, with premeditated

intent, to exterminate the Armenian people.

It is beyond the scope of this book to assess or to comment on whether or not there was a

deliberate or systematic genocide of the Armenian people during the First World War. This

section focuses on the role and the responsibility of the military in identifying and

reacting to the Armenian Rebellion of 1915 and 1916. Only a fraction of the massive

Turkish archival holdings are available to researchers, and these are carefully controlled

by the Turkish authorities. The records available to researchers in the Turkish General

Staff's archives describe a rising pattern of civil unrest, followed by an armed

rebellion. The available records also show an escalating response by the military

culminating in the mass deportation of the Armenians.

As a prelude, there had been considerable recent conflict between the

Armenians and the Ottoman government in the immediate aftermath of the revolutions of 1908

and 1909. During this turbulent period, Ottoman restrictions against minorities first

relaxed and then tightened. The hopes of the minorities, especially the Armenians and the

Greeks, who had thought that the ending of the sultanate and the establishment of a modern

constitutional structure would lead to greater autonomy and political inclusion, were

shattered when General Mehmut Sevket Pasa seized power. Disorder broke out throughout the

empire among minorities disappointed with this development and with increased taxes and

restrictions of civil rights. In particular, Armenians in Adana rose in revolt on April

14, 1909, and the army and the Jandarma in quelling the uprising subsequently killed many

thousands.

|

|

The Armenian population of

the Ottoman Empire in 1914 approached several million and the Armenian population of

the northeastern Ottoman vilayets was probably about 1.3 million people. There had

been numerous Armenian uprisings beginning in the late 1700s and culminating in the

1890s in infamous and widely reported massacres. While many of the Armenians were

loyal and law abiding citizens of the empire there had existed for many years

subversive Armenian societies dedicated to the establishment of an autonomous

Armenia. After 1909, internal dissent accelerated interest in these societies. In

1910, the Dasnaks (a revolutionary Armenian national society) launched a campaign of

terror in eastern Anatolia. Both Armenians and Turks were killed in the thousands,

and the army again was called upon to help restore order. Similar problems arose in

Albania, Kosovo, and Macedonia as other minorities became disaffected as well. The

Balkan Wars of 1912 and 1913 brought an end to Ottoman control of its European

empire, thus eliminating a substantial part of its minority problem. However, the

Armenians remained within the now truncated empire. By 1914,

nationalist/revolutionary Armenian societies were operating openly in Europe and in

Russia and were receiving support from many sources that sought the dismemberment of

the Ottoman Empire.

Within the empire itself, the Armenian community was increasingly alarmed by a

resurgent interest in Pan-Turanism, in particular, by the Turkish nationalist

theories of Ziya Gokal, who advocated the imposition of the Turkish language and

culture on the empire. Certainly a case can be made that these ideas appealed to

some members of the CUP, especially Enver Pasa. This cult of Turkish nationalism and

modernization found many adherents within the army as well. Gokalp's supporters even

made contact with non-Ottoman Turks outside the empire's boundaries. The Christian,

linguistically and culturally different, Armenians received the ideas of Gokalp with

great foreboding. Perhaps equally worrisome to the hard working and industrious

Armenians was Gokalp's advocacy of greater Turkish participation in the economy. In

any case, it was perhaps more than idle speculation by 1914, that the Turks intended

to consolidate their hold on the remaining empire in the Anatolian heartland, and

that they intended to impose some kind of cultural, linguistic, and economic Pan-Turanic

program on the empire's population. In the spring of 1914 the Turks intercepted

letters from Armenian committees expressing concern over these developments. Other

letters sent by the Tasnak Committee requested weapons from the Russians. In July

1914, the Ottoman Consulate in Kars intercepted a telegram outlining the smuggling

of four hundred rifles into the Eliskirt valley. Also during the summer of 1914, the

Armenian Committees conducted the important Erzurum Congress under the leadership of

the Tasnaks. Armenian representatives from every major Eastern Anatolian city were

present. Ostensibly conducted to peacefully advance Armenian concerns through

legitimate means, the Turks regarded the Congress as the seedbed for later

insurrection. It was here, the Turks were convinced, that strong Armenian-Russian

links solidified into detailed plans and agreements aimed at the detachment of

Armenia from the Ottoman Empire.

By September the commander of the Erzurum Fortress received a report that the

Armenian regiments in the Russian Army were mobilized and were conducting

war-training exercises. Indicators of potential violent intent accumulated as

Turkish authorities found bombs and weapons hidden in Armenian homes. The 4th

Reserve Cavalry Regiment patrolling from its lines in Koprukoy discovered Russian

rifles cached in Armenian homes in Hasankale on October 20. The tempo of army

operations against Armenian dissidents accelerated.

In early October 1914 (prior to the commencement of hostilities), the Turkish Third

Army was receiving reports of Armenians who had been ex-Russian soldiers returning

to Turkey with maps and money. There were reports from infantry battalions

concerning Armenian meetings at which large numbers of aggressively nationalist

people were gathering. In late October 1914, the Third Army staff informed the

Turkish General Staff that large numbers of Armenians with weapons were moving into

Mus, Bitlis, Van, and Erivan. Additionally disturbing to the military staffs at all

levels was an increasing recognition that thousands of Armenian citizens were

deliberately leaving their homes in Ottoman territory and traveling into Russian

held territory with most of their earthly possessions. Although Turkey was still

officially at peace with Russia, many Turkish officers were by now convinced that

Russia was actively conspiring to foment an Armenian (?rebellion?).

|

| |

The situation went from bad to worse

as Russia declared war on Turkey in November 1914. Throughout November, December, and into

January 1915, many similar reports to the Turkish General Staff outlined the danger posed

by armed Armenians in the Third and in the Fourth Army areas. Incidents of terrorism

increased, particularly bombings and assassinations of civilians and local Turkish

officials. On February 25, 1915, a ciphered cable went from the Operations Division of the

Turkish General Staff to the First, Second, Third, and Fourth Armies; the Irak Command; I,

II, III, IV, V Army Corps; and to the Jandarma Command. The cable contained the chief of

the Operations Division's newly issued Directive 8682 titled Increased Security

Precautions. This directive noted increased dissident Armenian activity in Bitlis, Aleppo,

Dortyol, and Kayseri, and furthermore identified Russian and French influence and

activities in these areas. The Operations Division directed that the Third and the Fourth

Armies increase surveillance and security measures. All recipients of the cable were

instructed to increase coordination among themselves. Finally, the cable specifically

directed that any ethnic Armenian soldiers should be removed from Turkish headquarters

staffs and taken out of important Turkish command centers.

The final measure contained in Directive 8682 was probably taken in response to a report

from the Ministry of the Interior's Intelligence division to the Turkish General Staff's

director of intelligence. In this report it was noted that the Armenian Patriarchate in

Constantinople was transmitting military secrets and dispositions to the Russians. From

February through July 1915, a great many additional reports from provincial officials and

lower level army units reinforced this pattern of allied intelligence gathering as well.

In the Third Army area, the disastrous Sarikamis

offensive had created a deplorable military situation. The army staff was trying to

restore combat effectiveness to its shattered infantry divisions while at the same time

trying to hold a very long front. Fortunately for the Turks, the battered Russians were in

a similar condition; however, the Russians were winning the reinforcement battle because

of their superior lines of communication. A massive Russian offensive was expected

following the spring thaw in 1915. Overlaid on this dismal situation was the increasing

belief by the Turks of an Armenian rebellion in the rear areas of the Turkish Third Army.

For the staff of the Third Army this represented a catastrophe of unimaginable

proportions. The main Armenian centers of population (and thus of potential armed

resistance) lay directly astride the only two metaled roads leading into the Third Army's

area of operations. Sivas, Erzincan, and Erzurum interdicted the northern route. Each of

these cities included substantial Armenian populations. Some contained Armenian

majorities.

Furthermore, Armenian activity in Konya, Adana, and Aleppo (in the Fourth Army's area)

interdicted the only railroad bringing food, war material, and reinforcements from the

west, through which the Third Army's supplies flowed as well. Since the Third Army had

only limited quantities of food, medicine, and military stores on hand, interdiction of

these key communications arteries spelled disaster. There was also the distinct

possibility of organized and armed Armenian groups rising in the Third Army's rear to

actively support and assist the anticipated Russian spring offensive. This was

particularly worrisome given the large numbers of Armenian men who had joined the

Russians, many of whom had left relatives and friends behind in Ottoman territory. The

Armenian threat affected the military situation not only for the Third Army, but

potentially for the Fourth Army in Syria and the Sixth Army in Mesopotamia. These

concerns, therefore, had to be addressed by the planning staffs of the Turkish Armies as

they prepared for operational contingencies.

It is difficult to pinpoint exactly when and where the rebellions broke out first. Many

western writers and historians have concluded that the Turks themselves deliberately

instigated the revolts by enforcing intolerable conditions on the Armenians. These acts

included murder, rape, and lesser humiliations, which served to provoke an Armenian

reaction. The Turks dispute this and today claim that it was the Armenians, encouraged by

the Russians and French in the aftermath of Sarikamis, who first rose in revolt.

|

|

IN fact, armed revolts by

the Armenians soon broke out. The most famous incident occurred when the Druzhiny,

an Armenian nationalist movement, seized the lakeside city of Van in fierce fighting

on April 14, 1915. The Turks responded by rushing the Van Jandarma Division to the

divy to contain and to crush the rebellion. There was bitter fighting as the Turks

besieged the city. Simultaneously the Russian Army began its long awaited offensive

into the region. This Russian army contained a large number of Armenians organized

into several army divisions of well-trained and highly motivated infantry regiments.

Although these soldiers were recruited mainly from the Armenian vilayets lost to

Turkey in 1878, their ranks included numerous expatriate Armenian citizens from the

Ottoman Empire who had fled to fight against the Turks. The Turks believed that the

Russians deliberately recruited these people because of their knowledge of the

terrain and peoples within the Ottoman Empire. The tactical situation around Van and

its approaches appeared to critical that the Turks rerouted the 1st Expeditionary

Force to assist in crushing the rebellion. Two Jandarma battalions assigned to the

28th Infantry Division were also pulled off the line and sent to Van. Fighting

around Van lasted into late May, when the Russians finally broke the siege and

relieved the Armenian defenders of the city. Other Armenian centers of population

soon followed suit and over the next several months revolts broke out in the cities

of Bayburt, Erzurum, Beyazit, Tortum, and Diyarbakir. Most of these revolts were

traced to the support and instigation of the Armenian nationalist committees.

Horrible massacres of Armenian males were committed in the Van region which were

widely reported by numerous neutral observers. Most of these were attributed to

Kurds and Circassians, although some were ascribed to Turkish forces. Rafael De

Nogales, a Venezuelan soldier of fortune fighting with the Turks, claimed in his

memoirs to have been told that local Ottoman officials had received secret orders to

exterminate all Armenian males of twelve years of age and older. Other witnesses,

including Americans and Germans with direct access to the ruling elite, claimed to

have been told about similar orders. Documentation on this point is contested by the

Turks. De Nogales remarked that the Armenians reciprocated in kind by slaughtering

large numbers of Muslims and also noted that the Armenian rebels were well equipped

with arms, ammunitions, and explosives. HE claimed that the semi-automatic Mauser

pistol seemed particularly abundant, and was an Armenian weapon of choice in the

close hand-to-hand fighting within the city of Van itself.

Turkish reaction to these armed rebellions escalated in the late spring and the

early summer of 1915. On April 20, Enver Pasa sent a ciphered message to the Third

Army headquarters confirming that Armenian and Greek soldiers were deserting to form

dangerous rebel bands. Enver noted that it was undesirable to use either regular

Turkish troops or the mobile Jandarma regiments against these rebels (these troops

were then badly needed at the front). He therefore directed that the local and

permanently based (static) Jandarma battalions be used to help capture the rebels.

He also recommended that a reward system of one Turkish lira per every captured

rebel be established to encourage local inhabitants to turn in the rebels.

A message from Muammer Bey, the Governor of Sivas, exposed a serious problem with

this plan. The governor noted that in his vilayet, although about fifteen thousand

Armenian men of military age had departed to join the Russians, another fifteen

thousand Armenian men remained in the vilayet . Unfortunately, conscription of all

Turkish men up to the age of 50 years old had left the local villages practically

unprotected and vulnerable to Armenian depredations. This condition made hunting

down the rebels problematic. The greater need by far, at least in Sivas, was simply

to provide for the protection of the Muslim villagers themselves, and the local

Jandarma were hard pressed to accomplish this.

|

| During this

period [of near-simultaneous allied attacks] almost every Turkish Infantry

Division would be committed to combat in a strategic situation akin to the Dutch boy

plugging the dyke with his finger. |

|

|

Enver

Pasha |

On April 24, 1915, Enver Pasa in his capacity

as the chief of the Turkish General Staff issued an important directive that noted

that the Armenians posed a great danger to the war effort, particularly in eastern

Anatolia and outlined a plan to evacuate the Armenian population from the region.

This directive also confirmed the Armenians' worst fears about the direction of

Ottoman policy regarding their status as a discrete cultural entity within the

Empire. It specified that Armenian males between sixteen and fifty-five years of age

would be deported. Furthermore, all Armenians would be directed to speak Turkish and

Armenian schools would be forced to accommodate this. All Armenian newspapers

throughout the empire would be closed immediately, although this may have been a

moot point since Enver had rounded up most of the Armenian intelligentsia (over

three hundred in Constantinople alone) previously on April 20. The April 24

directive specifically identified the six eastern Anatolian vilayets , Zeytun, and

the area south of Diyarbakir as the operational area affected by the evacuation

plan. It was intended to move the Armenians to the Euphrates Valley, Urfa, and

Suleymaniye. The order specified that the goal was to create an eastern Anatolian

demographic situation in which the ratio of Armenians would drop to 10 percent of

the local total of Turks and local tribesmen. Almost mocking the inhumanity of the

directive, it was specified that the Armenian families would draw lots to see who

would have to leave. Finally, the directive concluded by reminding all concerned

that the Armenians would be treated in a proper manner.

It would appear from this directive that the Turkish General Staff intended that

this evacuation would be orderly. Further guidance from Enver soon followed on April

29. In a ciphered instruction to the Ministry of War, all army commanders, all

fortress commanders, and to the Irak Command, Enver directed that all Armenian

leaders and "malicious" Armenians be arrested immediately. The Dasnak,

Huncak, and similar Armenian Committees in Constantinople and in the vilayets would

immediately be closed down and those who were regarded as harmful would be made to

stay in a more "suitable location."

Outside forces now conspired to exaggerate the growing problem of an actively

hostile Armenian population in eastern Anatolia. In Mesopotamia, on April 14, the

British began an offensive that would take them to the very gates of Baghdad itself.

On April 25, 1915, the British and French came crashing ashore at Gallipoli creating

a critically important fourth front that immediately threatened the power center of

the empire. The long anticipated Russian offensive in Caucasia began on May 6 with a

major attack down the Tortum Valley toward Erzurum. A second major Russian attack

also started toward the city of Van. These twin Russian attacks seemed aimed at

Turkish cities containing large Armenian populations. Indeed, the Armenians in Van

had already risen in rebellion. Furthermore, the timing of the allied attacks,

nearly simultaneously on three sidely separated fronts, indicated allied

coordination and mutual support hitherto unseen by the Turks. There was a sustained

period of crisis for the Turkish General Staff in 1915 — it began on April 25 and

it lasted until the fronts were stabilized in the fall of 1915. During this period

almost every Turkish Infantry Division would be committed to combat in a strategic

situation akin to the Dutch boy plugging the dyke with his finger. Quite literally

in the very middle of this sea of competing priorities and in a position to

interdict the military lifelines of the empire, lay the Armenians, a subject people

heavily armed, belligerent, and now actively engaged in open rebellion.

The strategic dilemma of early May 1915 caused a major shift in the philosophical

and practical basis of the government's policy toward Armenians, as Enver Pasa

reevaluated the mounting problems and decided to take a radically different

approach. This shift in policy would have severe and heartbreaking consequences for

the entire eastern Anatolian demographic landscape, and it produced unintended

effects that linger into the contemporary world. On May 2 Enver wrote to the

Ministry of the Interior outlining his thoughts on the best way to tackle the

Armenian situation. He thought it necessary either to drive the Armenians, then

living around Lake Van, into Russian territory or to disperse them throughout the

Ottoman Empire. Enver's preference was to drive the rebels, their families and their

headquarters away from the Russian border and then to resettle the area with Muslim

refugees from abroad (Turkey had still not fully assimilated the millions of Turkish

and Balkan Muslim refugees who had fled into the empire after the Balkan Wars).

Finally, Enver asked the Ministry of the Interior to select an appropriate plan,

practices, and methods to accomplish these ends.

|

| |

Clearly what had begun as a temporary and partial evacuation of

rebellious Armenians had now changed, philosophically and practically, into a mass

deportation of a more permanent nature. Moreover, it was now apparent that the military

was attempting to involve or to include the Ministry of the Interior in the promulgation

of the deportation. As the full scope of the Van rebellion and associated Armenian

rebellions in the Third Army area became apparent the military tried to enforce and adhere

to the existing policies. However, the existing security measures were inadequate to deal

with the problems at hand, in particular, the pressing enemy offensives drained almost all

regular Turkish military power into the front lines. As Enver's new policy ideas began to

take hold in the capital, the military grappled with ways to come to terms with the

dilemma. Turkish reactions grew harsher. A new provisional law was passed on May 27, which

established military responsibility for crushing Armenian resistance. The military was

also fully empowered to round up the Armenians, either collectively or individually in

response to military needs or in response to any sign of treachery or betrayal, and to

transfer populations. It is important to note here that this law still maintained the

operative notion that direct action against Armenians would only be in response to

military necessity or in reply to hostile behavior.

On May 30, 1915, the now infamous Regulation for the Settlement of Armenians Relocated to

Other Places because of War Conditions & Emergency Political Requirements was

established under the oversight of the Department of Settlement of Tribes and Immigrants

in the Ministry of the Interior. This regulation fixed responsibility for transportation

with local officials and additionally charged them with the protection and lives of the

Armenians en route to their new homes. Importantly, the regulation established that the

new areas and the new villages for the Armenians would be established at least twenty-five

kilometers from the route of the Baghdad Railroad. It was clearly specified that the

health, boarding, and welfare of the deportees would remain a high priority.

Thus cumulatively, the mechanism for the deaths of many deportees en route was now

established. There was no central headquarters in overall charge of the deportation. To

the military fell the responsibility to round up the rebellious Armenian population. To

local officials fell the incredibly difficult responsibility of arranging transportation,

lodging, feeding, and health care for an unwilling Armenian population of mostly women,

children, and the elderly To the Ministry of the Interior fell the responsibility of

finding suitable locations at the end of the journey for the deportees to reestablish

their lives. Compounding this critically flawed organizational command structure was the

military mandate to relocate the Armenians to a place somewhere other than near the route

of the Baghdad Railroad. There is nothing in the record to indicate that the military, the

Ministry of the Interior, and local officials coordinated their efforts to alleviate the

horrible conditions suffered by many of the deportees.

A human disaster of huge proportions loomed on the horizon. Administratively such a scheme

wildly exceeded Turkish capabilities. Even had the Turks been inclined to treat the

Armenians kindly, they simply did not have the transportation and logistical means

necessary with which to conduct population transfers on such a grand scale. Military

transportation, which received top priority, illustrates this point, when first-class

infantry units typically would lose a quarter of their strength to disease, inadequate

rations, and poor hygiene while traveling through the empire. This routinely happened to

regiments and divisions that were well equipped and composed of healthy young men,

commanded by officers concerned with their well being. Once again, in a pattern which

would be repeated through 1918, Enver Pasa's plans hinged on nonexistent capabilities that

guaranteed inevitable failure.

|

|

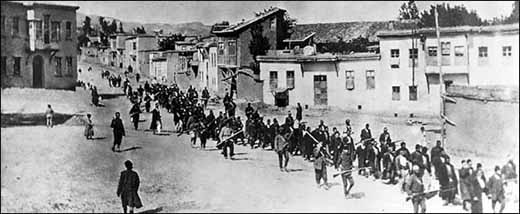

"Armenians

in the Ottoman Empire being marched to a prison in 1915" read the caption of

this

photo, published in the New York Times' atrociously one-sided

article, "Turks Breach Wall of Silence on Armenians," March

6, 2004. Yes, you read that date correctly: 2004. Even at this stage, the New York Times cannot bring themselves to be

objective on this "genocide" issue. What kind of a "prison"

were these people being marched to, exactly? There were no Dachaus at the end of

their destination. The ad hominem is unconscionable, particularly now, in the 21st

century. |

|

Compounding the

implementation of these policies was the continuing Armenian Rebellion, which

included bombings, assassinations, and the wholesale slaughter of Muslim Turkish

villages. In some places the rebels even gained the upper hand. The rebels in the

city of Van were ultimately relieved by advancing Russian forces. At Musa Dag in

Cilicia, highly organized Armenians fought the Turks for forty days. These events

were bound to inflame an already angry Turkish population and bureaucracy. In spite

of this, the Ministry of the Interior continued to muddy the organizational waters

by establishing further regulations that safeguarded the homes of the deportees.

According to the ministry, the homes of the deportees were to be sealed and

possessions left behind were to be cared for. If the Armenians' homes were used as

temporary lodging for Balkan immigrants the new occupants would be liable for any

accrued taxes and for damages. Certainly there were many mixed messages with all of

their associated and unsaid complexities to be found in the rapidly evolving legal

mechanisms which governed the deportation and relocation of the eastern Anatolian

Armenians. The ponderous and complex wheels of the relocation process now began to

grind the Armenians into dust.

At the highest levels, Enver Pasa and the military staffs appear to have generated

the basic idea of the forced evacuation of the Armenians in response to a military

problem which threatened the security of the Turkish Third Army and therefore of the

empire itself. It is beyond question that the actuality of the Armenian revolts in

the key cities astride the major eastern roads and railroads posed a significant

military problem in the real sense. In point of fact, there were heavily armed and

organized bands of Armenians operating in concert with their Russian allies. This

problem in combination with the allied offensives in Caucasia, Mesopotamia, and at

Gallipoli caused an acceleration of the Turkish will to deal with an issue of

growing military concern. The main body of the army itself appears removed from the

Armenian deportations because of the strategic crisis of 1915 which kept regular

army units at the front and away from the implementation of the Armenian directives.

Most of the mobile Jandarma regiments and battalions would likewise have fallen into

this category. As to the question of which military units actually participated in

the initial consolidations and delivery of Armenians into pipeline, the answer is

not clearly established in Turkish official histories. It is likely that the work

was done by local Jandarma units and Ministry of the Interior forces which remained

in the vilayets for village and area protection. Kurdish and Circassian volunteers

who probably had axes to grind with their Armenian neighbors usually augmented these

units. De Nogales says as much in his memoirs. The highly visible deportation began

in earnest in the early summer of 1915 and, as detailed by numerous German and

American observers, violence against Armenian noncombatants began almost

immediately. By the early fall, formal reports of abuses against Armenians were

beginning to filter up the military chain of command to the Turkish General Staff

and to the Ministry of War.

|

| |

By mid-1916, most of the Armenian

population had been forcibly removed from the eastern Anatolian vilayets and from the key

cities along the east-west railroad. At this point, the Armenians ceased to be a military

concern for the Turkish military staffs. Numbers of Armenian males remained alive as the

Turkish Army continued to use Armenian manpower in its labor battalions until the end of

the war. This is particularly true of the western, and predominately Catholic, Armenian

population of the empire. Additionally, large numbers of eastern Anatolian, primarily

Orthodox, Armenians survived by fleeing to join the Russians.

In the end, hundreds of thousands of Armenians died during the Armenian Rebellion and

deportation of 1915-1916. A similar number of Muslim Turks also died during the Armenian

revolts and during the Russian occupation of Erzurum, Van, Erzincan, Trabzon, and

Malazgirt. To be sure, many Armenians, particularly leaders and men of military age were

immediately killed or massacred early on before entering the deportation flow. Many more,

especially the elderly and the infirm, died en route from apathy and neglect, or were

murdered outright, as the deportees were passed from local official to local official in

an ambulatory pipeline that resembled a decaying daisy chain. Finally, the geographic

constraints imposed on where the Armenians could ultimately be allowed to settle imposed

long term starvation as they were sent to arid locations outside the fertile and

well-watered route of the Baghdad Railroad. It was a recipe for disaster with profound

historical, moral, and practical consequences which persist into the present day.

|

A Review of Erickson's Book

|

Ordered to Die: a History of the Ottoman Army in the First World War.

(Book reviews: Turkey). John F. Guilmartin Jr.

The Middle East Journal

56.1 (Wntr 2002): p168(3). From Expanded Academic ASAP.

Ordered to Die: A History of the Ottoman Army in The First World War, by Edward J.

Erickson. Westport, CT and London, UK: Greenwood Press, 2001. xxii + 216 pages.

Maps. Appends to p. 249. Sel. bibl. to p. 255. Index to p. 256. $62.50 paper.

The historical consequences of the First World War were enormous, and to appreciate

them fully one must look beyond immediate diplomatic and political repercussions to

an understanding of how the war was waged -- how the warring nations mobilized and

deployed their human and economic resources and to what effect. Armies were

particularly important, for the First World War was first and foremost a struggle

between armies; their successes and failures in 1914-18 not only shaped the course

of the conflict and determined its outcome, but cast long shadows in the post-war

era. Nor is the matter one of simple demographics: Verdun, the Somme and Caporetto

owed their political significance not just to the staggering loss of human life, but

to how those lives were lost. The French high command's bungling produced the May

1917 mutinies that brought General Petain to prominence; Caporetto begat Mussolini;

the tactical and operational competence of the German high command combined with its

strategic ineptitude to lay the groundwork for the stab-in-the-back legend; and so

on. The Ottoman Army -- or Turkish Army, as the author of the work under review

prefers, and with good reason -- looms large in this regard, for it formed the core

around which the Turkish Republic coalesced. Nor was the role of the Turkish Army in

the conduct of the First World War inconsequential. Beyond the defense of Gallipoli,

the one generally acknowledged Turkish triumph, the Turks engaged major Russian

forces in the Caucasus, sent significant expeditionary forces to fight alongside the

Germans and Austro-Hungarians in Romania and Galicia, and fought with success in

Mesopotamia and Palestine until well into 1918, when the Austro-Hungarian and German

armies were dissolving.

The Turks have received short shrift in the history of World War I. This is largely

a function of Anglo-American historiographical predominance; directly in that few

modern military historians read Turkish, let alone Ottoman; and indirectly in that

Anglocentrism has focused attention on Britain and the Western Front. In the basic

texts, save for the obligatory chapter on Gallipoli and perfunctory mention of

Mesopotamia, British General Allenby's Palestine campaign, and the Arab revolt, the

Turks are all but ignored. Drawing on the Turkish Army's voluminous official

histories and selected primary sources transcribed into modern Turkish, the author

of the work under review has gone far to redress this imbalance.

The result is a comprehensive assessment of the strategic dimensions of the Ottoman

Empire's military commitment to the Great War, beginning with an overview of

available human and materiel resources, war plans, and initial execution. In this

arena, the Ottoman Empire, far and away the least industrialized of the major

combatant powers, did remarkably well. That the Turks were ultimately ground down in

the massive war of attrition that ensued is hardly remarkable; that they resisted as

long as they did is. The devil is in the details — too many to address in a brief

review — which the author lays out for inspection in a well-organized and

closely-reasoned narrative. Points of particular interest are the impressive

competence of the officers of the Turkish General Staff, their effective cooperation

with their German counterparts (Turks served under German command and vice versa

with minimal friction), and the Armenian genocide. The author's treatment of the

latter issue is admittedly inconclusive, for his research focus was on the Turkish

Army and not on the national leadership. However, he demonstrates (at least to this

reviewer's satisfaction) that the appalling loss of life can be attributed, without

invoking a conscious policy of extermination, to the effects of divided lines of

authority, administrative ineptitude, paucity of resources, and sheer callousness in

relocating Armenians, many of whom were in an active state of armed rebellion, away

from strategically critical military lines of communication.

Thoroughly documented and supported by no less than seven appendixes addressing,

inter alia, organizational structures, senior leaders' biographies, and casualties,

this work makes major contributions to the historiography of World War I and the

Turkish Army. Well-produced and edited, albeit expensive for the individual, this

book will be the definitive work on the subject for the indefinite future and is

highly recommended.

John F. Guilmartin, Jr., The Ohio State University

Holdwater: The

emphasis above is mine. Note how Mr. Guilmartin indicates that he is satisfied there

was no "conscious policy of extermination," and yet he still calls it the

"Armenian genocide"..!

Thanks to Hector, for the review

|

| |

Of interest:

Vahakn Dadrian Objects to Edward

Erickson

Ed Erickson Responds to Vahakn Dadrian's Libel

|

|