|

|

The following is from Prof. Stanford Shaw's "From Empire to Republic: The

Turkish War of National Liberation, 1918-1923," 2001, pp. 236-263. While published in English, the book appears

to be difficult to find outside of Turkey.

It's upsetting so many accept their Ottoman historical information from

charlatans such as Vahakn Dadrian and the gang of genocide scholars; some of

these underhanded people joined in the campaign to try and discredit Prof.

Shaw, because he told the truth, and had the audacity to go against their harmful genocide propaganda. Below is a real

scholar at work, who took all relevant information into consideration; the

following is the real history of what took place.

Thanks to Sevgi.

|

|

|

| |

...public officials as part of the religious requirement of alms (zakat) to help

those less fortunate than themselves, while the actual work was carried out by upper-class

ladies who volunteered to spend between twenty and thirty hours every week helping the

less fortunate. Every month, the committee took in as many as four hundred children aged

less than fifteen years, providing them with housing, food, clothing and the rudiments of

an elementary education before sending them to the Imperial Trades School (Dar al-Sanayi),

where they were taught a useful trade before being sent out as apprentices so they could

be replaced by others. Children aged over fifteen were sent to the Central Police building

in the Pangaltt section of Istanbul, where rooms were set aside to house and feed them as

well as to teach them to read and write as well as trades such as iron mongering and stone

cutting. The many male children of all ages who were found to be mute or deaf and dumb

were taught to be shoemakers and furriers, while the girls were taught to sew and cook so

they could become maids and house workers.337

While the British refused to help the Muslim refugees on the grounds it was beyond their

resources, Winston Churchill got the British cabinet to agree to provide substantial

assistance to the Russian Czarist refugees because they had fought against the Bolsheviks:

The Secretary of State for War raised, as a matter of urgency, the

terrible and destitute condition of the horde of refugees from the Crimea now concentrated

in the Constantinople area consequent on General Wrangel's collapse. All reports agreed

that these people were in a most desperate situation, crowded, without food, in hastily

improvised camps or still on board ship, exposed to great risks of an outbreak of

pestilence. The French were rendering assistance and had dealt with 40,000. The Americans

were also stated to be helping up to the limits of their capacity on the spot. Mr.

Churchill stated that on the previous Monday he had sent a telegram to the General Officer

Commanding in which, after repeating the decision of the Cabinet to avoid any re-equipment

of General Wrangel, he had informed him that he was not debarred from giving such

assistance as he could on the grounds of humanity. Mr. Churchill now asked that the

General Officer Commanding, Constantinople, might be allowed to spend up to 20,000 pounds

sterling on the work of relief... 338

RESETTLEMENT OF REFUGEES AND THE RESULTING VIOLENCE

By November of 1917, long before the war had come to an end, the Ottoman government had

discovered that its policy of resettling or deporting large groups of people for strategic

or other reasons was a resounding failure. Removing the few able bodied men who were left

after the massive conscription begun at the start of the war had disrupted both

agriculture and trade, decimating the market place and adding to the results of the

British naval blockade of the eastern Mediterranean to create massive shortages of food,

with supplies far short of what was needed to feed the cities, let alone the thousands of

refugees living in camps around the country. Starting in late March, 1918, therefore, long

before it was required to do so by the Armistice of Mondros, the Ottoman government worked

systematically to resettle Armenians, Jews, Turks and Arabs who had been deported,

relocated, or driven out of their homes in the war zones during World War I.339 The

Department of Tribes and Refugees (Asayir ve Muhaddn Miidiriyet-i Umumiyesi), which

originally had been established in the 1860's as a branch of the Ministry of the Interior

to care for the thousands of Muslim refugees fleeing from persecution in the newly

independent Christian states of Southeastern Europe, and which also had cared for the

thousands of Jewish, Muslim, and White Russian refugees fleeing from Russia since the

1890's, was put in charge of facilitating the returning refugees' return to their homes.

District Refugee Departments (Mühacirin Müdüriyeti) were set up in all the major

provincial centers to organize and carry out its work on the local level. The Central

Office of Deportation Committees (Heyet-i Teftisiye Müdüriyet-i Umumiyesi) that

was established in Istanbul to send out investigation committees (Heyet-i Teftisiye)

to the provinces to gather evidence regarding crimes that had been committed during the

deportations, also ordered them to find out where the deportees were and where they wanted

to go so that arrangements could be made to send them back to their homes as soon as

possible.340

|

|

Deportation caravans carrying Armenians and Greeks to exile in interior provinces

were ordered stopped and their passengers returned to their homes. 341 The

provincial and district governors were ordered to help the investigation committees

draw up detailed lists of all the Armenians and Greeks who had lived in the areas

under their jurisdiction before the war, how many had been deported and to where,

how many had been exempted from deportation and why, how many of those who had been

deported from other places were still living where they had been placed, and how

many had fled and could no longer be located. Detailed statistical reports were also

drawn up showing the ethnic populations of the districts and provinces before and

after the war so that they could be submitted when required to the Paris Peace

Conference. 342 All Armenians who had been imprisoned for political crimes had to be

released at once so they could join the caravans returning the deportees to their

homes, but Greek political prisoners, like those Ottoman Greeks who had deserted

from the army and fled abroad, had to remain where they were until exchange

agreements were made by treaty between the Ottoman Empire and Greece. 343

Exemptions, however, were provided for Greek political prisoners whose families were

already living in the provinces that they wanted to go to. 344

|

|

|

Prof. Stanford Shaw, from

the documentary

THE ARMENIAN REVOLT

|

On the basis of the reports, Armenians and

Greeks from Izmir who had been sent across the deserts to Syria, and the leaders and

many members of the Armenian Dashnak and Hunchak revolutionary groups, who had been

concentrated at Musul, were ordered to be returned to their homes at once. 345

Most of the deportees, however, had never been sent very far from their homes. Many

had been held in camps either in the same county and province as their homes,

sometimes in neighboring provinces, sometimes in sectional deportation centers set

up at places like Malkara and Uzünkoprü for Greeks from eastern Thrace, Mudanya

and Gemlik, on the shores of the Sea of Marmara, for Greeks from the Bursa area,

Kayseri for those from south central Anatolia, Izmir for much of central Anatolia,

Ankara for the north central and western areas, Bitlis for the northeast, Beypazari

and Ayas for the central Black Sea coastal area around Samsun and Bafra, and Urfa

and Maras for those from the Southeast. Most of those from Bitlis and Trabzon had

been kept as close as Erzurum, Sivas and Mamuretiilaziz. Sinop had been the

detention center for those from Kayseri. Mardin and Nusaybin had been used for those

from the Diyarbekir area. Large numbers of the deportees had, in fact, been sent to

Istanbul, where they remained throughout the War of National Liberation, at first

because of lack of transportation, and later because of the chaos caused in western

Anatolia by the Greek invasion and the activities of the National Forces as well as

of Greek and other bandits.346 These were able to return to their homes very

quickly, therefore, often within two or three weeks depending on availability of

transportation and the conditions that existed in their original homes. As a result,

most of the deportees were back in their home towns even before the Armistice was

signed, and the remainder within a few weeks afterwards.

In order to avoid the deaths and suffering that had taken place during the Armenian

deportations that had been started with little advance preparation or supervision in

1915, the returning caravans were ordered to be 'well organized and sent by

well-known roads. 347 Governors were made personally responsible for the safety and

well-being of those being transported back to their homes, and were particularly

warned to watch out for the kind of misconduct which some local officials had

committed during the war. 348 Those in camps very close to their own homes were sent

home at once by the first available conveyances or on foot.349 When they had to go

by caravan for long distances, they were delayed by as much as a month after the

orders were given so that the routes to be followed could be carefully prepared and

the provincial and local officials alerted to have shelter and food ready for the

refugees when they arrived and to make sure that they were well housed and fed so

they would not try to break away from the caravans and go it on their own, where

conditions inevitably would be much worse. The permits to return also were staggered

so as not to overburden the caravans as well as the places to which the refugees

were returning.350 The refugees sent home in the late autumn had to be expedited so

they could arrive before the onslaught of winter. Otherwise they had to be kept

where they were until the spring.351 The women and children who were coming to Sivas

by the hundreds from Erzincan and Refahiye had to be kept in those places and

provided with housing and food through the winter months until they could be sent to

their homes in guarded caravans during the spring and summer. 352

Special attention was paid to the health of the deportees as they walked along the

roads.353 One local building in each town or village with space for two hundred beds

had to be set aside as a hospital for injured or ill deportees.354 Guards were

provided at all stages to prevent the kind of attacks which had so decimated many of

the Armenian deportation caravans in 1916.355 Because of the shortage of train and

truck transportation. those who could walk and care for themselves along the way

were sent before those who were old and ill and would have difficulty going on foot.

Wagons were provided for women and children as well as for elderly men who were not

physically capable of walking.356 \Men who had land and shops in their homes which

they could use to begin engaging in trade and commerce were given preference over

laborers.357 Many of those whose departure was postponed and who had attempted to

return to their homes on their own soon found themselves without food or shelter,

lying beside the roads while desperately waiting for help, leading the Istanbul

government to order its provincial officials to both send out squads to find such

people and return them to the camps as well as to take special precautions to

prevent refugees from returning home except in organized caravans in which they

could be protected and cared for.358 When the Ministry of the Interior discovered

that the Commander of the Third Army had forced 'orphans and poor and helpless

refugees around Harput and Dersim to go on foot to Maras and Elbistan,' he was

admonished and order[ed] to send them properly and safely, and only when caravans

were ready to take them.359 Where possible, steamships were used to transport

refugees from the deportation locations to the ports nearest their homes.360 Despite

all the preparations, however, food often was in short supply along the road, and

the available rations often were supplemented for those who agreed to work for a few

days on local roads and railroads. On one occasion, the men in an Armenian caravan

had been given extra food in return for working on a railroad line near Nusaydin,

leading the local Muslims to complain that the Christians were being favored. After

a quick wire to Istanbul for instructions, the local army commander told the Muslims

that they also would get extra food if they joined the work crews, which they did.

361

|

| |

All costs for transportation and food for all deportees and other refugees were paid by

the government when needed out of the special government appropriations previously

budgeted for mobilization expenditures (seferberlik tahsisat), and after these

funds ran out, from special refugee appropriations (mühacirin tahsisati) 362

Subsequently, however, because of critical shortages of funds, the Istanbul government

decreed that only those who were most in need were to be provided with daily maintenance

payments (yevmiye) by the government authorities, while those who had returned to

their homes were cut off further support after a period of two weeks to give them time to

resume their occupations and support themselves. Soon after the Armistice was signed,

however, the funds ran out altogether, since the Allies would not allow the Istanbul

government to collect the bulk of the taxes owed it by foreign residents within its

jurisdiction, leading to inability to pay its civil servants as well, so assistance to

p243 refugees after that time was limited to those who were in desperate need, and then

only when the money could be found.363

All of these refugees were ordered to be immediately returned to their homes within the

Empire, or enabled to return if they lived in foreign countries. Temporary housing, food

and clothing as well as seed and tools were provided to all these returning deportees to

start them back on the way to normal lives, Armenians and Greeks who had fled from the

Empire to Greece, Europe or North America who wanted to return were to be allowed to do so

with the exception of Ottoman Greeks (Rum) who had deserted (firari) the army

during wartime; they were considered criminals whose status had to be arranged by

negotiations between the Ottoman Empire and Greece, most likely in the form of an exchange

arrangement for Ottoman soldiers held prisoners by Greece. All other deserters, however,

including Armenians were allowed to return without punishment since a general pardon was

issued for all such persons late in December 1918, 364 Citizens of Greece, however, as

well as of the other Entente states, were free to enter the Ottoman Empire and to travel

freely within its boundaries, 365 Native Ottoman Armenians and Greeks who had taken the

citizenship of any of the Allied countries were treated like other citizens of those

countries, and they were free to travel and o enter and to leave the country as they

wished. 366 On the other hand, native Ottoman Christians who had taken up the citizenship

of Germany and Austria were deported along with other citizens of those countries, though

Bosnian Muslims and native Ottoman Jews who had acquired German or Austrian citizenship

were allowed to remain in the Ottoman Empire if they became Ottoman subjects.367.

Deportees or those who had fled abroad who had been tried and convicted of crimes were not

to be resettled.368

Detailed regulations were issued to care for the Christian refugees. The Armenians and

Greeks who did not want to return to their original homes had to be helped to settle

wherever else they wished, whether it be the places to which they had been settled during

the deportations or elsewhere.369 All immovable and movable property was to be returned

intact.370 If the original Armenian and Greek property owners had died, whether they had

been deported or had fled from the Empire of their own volition, their properties were to

be turned over to their heirs.371 All means had to be used to prevent the returning

Armenians from being left in the open after they returned to their home towns and

villages.372 Local officials were warned to do all of this in such a way so as 'not to

leave the dispossessed Muslims in misery and neglect,' though how this was to be

accomplished was not made clear.373

|

|

One of the most difficult problems which had to be faced during the Armistice

years was what to do about Christian women and children who had been protected,

housed and cared for in Muslim homes during the war. Many of the women had married

Muslims, converted to Islam and born Muslim children. Many had married and born

children but had not themselves converted. A few had been forced to convert, most

had done so willingly. Most Armenian and Greek children had been housed and

protected by Muslim families without being converted, but some of the younger ones

did not know what they were and had accepted the religion of their new parents.374

Thus American missionary Mary L. Graffam reported to American commissioner Louis

Heck that, much to her surprise and unhappiness, 'For some reason or other all the

girls and children in Moslem house... resist violently all efforts of their

relations to take them away... '375 When, then, was to be done with them? Wartime

propaganda in the Allied countries had insisted that all Christian women and

children had been forcibly 'kidnapped into Muslim harems,' and that all wanted to

return to their original communities, families and religions. From the very first

days of the occupation, therefore, the occupying powers forced the Ottoman

government to order tlIat all Christian women and children found in Muslim homes,

who were identified as such by Christian authorities and missionaries, whether or

not they had converted to Islam, and even when they could produce documents

showing that they had been born to Muslim parents, be turned over to the

missionaries or the Christian communities and converted or reconverted [to]

Christianity, regardless of whether they wanted to or not. Forced conversions and

marriages were automatically annulled unless the Armenians or Greeks petitioned to

remain in the Muslim religion and with their Muslim husbands.376 Armenians and

Greeks who had been sheltered in Muslim homes during the wartime deportations

without marriage, conversation or any other change in their status also had to be

released to their communities so that they could be returned to their homes.377

Armenians and Greeks who had converted to Islam during the deportations, and even

before World War I started, including women who had married Muslim husbands and

born Muslim children were allowed to return to their old religion with their

children by getting a statement (ilmühaber) from its religious chief and

submitting it to the local mayor (muhtar) for registration and issuance of a new

identity card (nüfüs tezkeresi) through the normal Ottoman population

registration (nüfüs) procedures.378 In places where Christian millet

authority was not available, the children had to be turned over to the director of

the nearest local Christian missionary school (kolej müdiri), if possible

in the presence of a priest.379

Many women and children who were forced to return to their Armenian or Greek

families and communities found themselves isolated and often punished due to their

Muslim upbringing, leaving them in absolute destitution until the Ottoman

government again arranged to care for them.380 As a result of such difficulties,

the policy later was modified, however, so that it applied only to minors aged

twenty or less who were living in Muslim homes, with those above that age allowed

to choose whether to remain or leave.381 Later the age requirement was reduced

even more to ten.382 This policy applied, however, only to those who were already

in Muslim homes. There still were difficulties. Young Armenian and Greek children

who had lived most of their lives with Muslim 'fathers' did not want to remain

with Christian 'strangers', whether real parents or not, particularly since the

latter often treated them with suspicion and even hostility because of their

Muslim upbringing, causing many of these children to flee into the streets, where

the Ottoman government ordered local authorities to pick them up once again and

return them to their Christian communities on the grounds that these children were

now Christian and therefore were entirely the responsibility of their own

communities. 383 Continued refusal of originally Christian women and children to

leave their Muslim homes led to complaints by the Armenian and Greek church

authorities, to which the Allied police responded by forcing the persons in

question to leave their families whether they wanted to or not. 384 Another

problem involved reports that Christian missionaries were kidnapping young Muslim

children off the streets and converting them to Christianity before they were old

enough to know what was happening to them.385

In the provinces under the control of the Istanbul government, orphans who clearly

identified themselves as Armenian or Greek were turned over to their own millets

for care in those towns and cities where the millets had their own orphanages or

other facilities to care for them, though in many cases neither the orphans nor

the families wanted them to leave. The only exceptions that could be made

originally involved Christian women and children living with Muslim families in

areas where there were no Christian community organizations or families to whom

they could be given. In such cases alone were they allowed to remain with their

Muslim families, under strict supervision, until arrangements could be made for

their transfer to other places where Christian community organizations could take

them in.386 For the thousands of orphans who identified themselves as Muslim as

well as Christian orphans found in areas where the Armenian and Greek millets had

no facilities or were unable to care for them for other reasons, the government

established orpanages in all the major provincial centers, sometimes run by

government officials, but most often by the Red Crescent organization based in

Istanbul, helped by the privately organized and financed Protection of Children

Society ( Himaye-i Etfal Camiyeti).387 Manyof the older refugee orphans who

were of school age were sent directly to trade schools to learn something which

would fit them to go out and support themselves as soon as possible.388 The

Ottoman government was uncertain what to do about Armenian men, women and children

who continued to apply to local officials to convert to Islam long after the

occupation had begun, fearing that to accept their requests would bring upon them

new accusations of 'forced conversion,' while rejection would violate one of the

most fundamental tenets pf Islam, Finally, a compromise was developed, with the

government requiring all such applicants to discuss their requests with an

Armenian priest in the presence of an Allied military or civilian official before

they were allowed to convert. 389

Most of the thousands of children who came

directly to Istanbul and other cities where the Allied occupation authorities were

in control were turned over to missionary rescue organizations, who automatically

identified them as Christians and assigned them to Christian families even though

many in fact were Muslims and Jews and identified themselves as such at the time and

later on when they grew to adulthood.390 In September, 1919 French Military Governor

in Cilicia, Edouard Bremond, issued orders that all Christian women and children

living in Muslim homes anywhere in the area had to go to Christian homes within a

week unless they specifically went to the office of the High Commission to ask

permission to stay with their Muslim husbands or fathers. Needless to say, when they

did go to ask permission, missionaries were at hand to try to convince them to alter

their decision.391

|

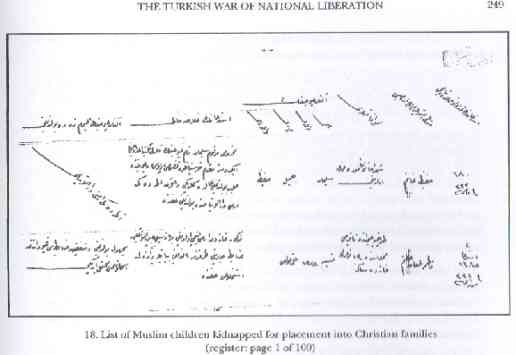

18. List of Muslim children kidnapped for

placement into Christian families (register: page 1 of 100) |

Despite these problems, British High Commissioner John de Robeck, however, praised

what was being done in a report to London:

...I have the honour to invite Your Lordship's attention to the

following considerations and expression of my views respecting the restitution of

Christian women and children found in Moslem homes.

|

|

|

Vice-Admiral John Michael

de

Robeck (1862-1928) ; led the Dardanelles Campaign, and

served as High Commissioner at

Istanbul 1919-20.

|

2. Dealing firmly with the

question of children so situated, it would appear that the procedure which is in

operation at Mosul, namely that children are only removed after enquiry through

Mohammedan Courts, and only then when the applicant is a near relation, is too

restricted, and that guardians and priests should also be accorded the right to

claim restitution of a child. Children have not discretion, and to leave them in

Moslem hands tends to put a premium on forced conversion and massacre. Moreover, it

should be borne in mind that in numerous cases there are no near surviving relatives

to apply for the child.

3. In cases where a child is

indisputably and demonstrably Armenian (or Greek), I consider that its

surrender ought to be effected, irrespective of whether it has become accustomed to,

and happy in, its new home, or not, and that such child should there and then be

handed over to its relatives, the local priest of the community, or the

missionaries.

4. The difficulty of settling the nationality of orphans reclaimed from Moslem

houses in Constantinople has been considerable. As stated in my telegram

above-mentioned, the establishment and operation of a 'Neutral House,' although many

children whose nationality would otherwise not have been ascertained have thereby

been recovered, have caused considerable feeling. The original procedure has now

been altered. A 'Neutral House' managed and staffed entirely by American or British

ladies has been instituted. There are grounds for hoping that this will prove more

efficient and popular than the previous one, where the decisions as to nationality

were taken by a mixed Armenian, Turkish and American Committee, and were the

attendants were Armenians and Turks.

5. In view of the partial document which this system has evoked, I would hesitate to

recommend its adoption save in areas rendered especially suitable by the presence of

effective British control.

6. The question in regard to married women is even less simple of solution. Some of

them have been married to their husbands for four years and experience shows that in

many cases they do indeed prefer to remain with them.

7. Some distinction may be made according as they have or have not reached the age

of discretion; and in cases where they have borne children to their Moslem husbands

this factor may also bear weight. It would not appear possible to fix an arbitrary

age limit as regards years of discretion, which should rather vary in different

parts of the Empire.

8. While opposed to the forcible removal of married women of mature age, I consider

that all possible encouragement and assistance should be afforded them with a view

to their leaving their Moslem husbands and rejoining those of their own race and

religion. And as regards those who have not reached years of discretion, I am of

opinion that their forcible removal is frequently both justified and desirable.

Cases where children of from 11 to 15 have been married under compulsion by Moslems,

with the express intention of frustrating their subsequent recovery by those of

their own race, are far from infrequent.

9. According to the Mosul practice, the question of the abandoning of their husbands

by Armenian women is left to the Turkish law, This weighs the scales heavily against

the women, whereas I consider that the contrary should be the case.

10. As regards both women and children, the measure of success attained must depend

on the personal influence and tact of the British officials and on local conditions.

Even were the Ottoman Government to pass a law, it would remain largely a dead

letter.

11. I am fully alive to the very great difficulties which any intervention in the

subject under discussion entails. I submit, however, that. it is a matter in which

it would be unthinkable to refrain from action, even if some measure of odium be

inevitably incurred thereby. For our efforts will result in some slight reparation

being made to the Armenian communities, and will moreover tend to act as a deterrent

as regards possible future massacres...392

The terrible scenes that resulted were described by the eminent Turkish author

Halide Edib (Adivar) in her published recollections of the period:

... Taking the Armenian children from the Turkish orphanages was

becoming a tragic sight. A committee was founded, presided over by Colonel Heathcote

Smythe, and it was attempting to find the Armenian children and separate them from

the Turkish children. They had rented a house in Shishli (a quarter of Istanbul).

The majority of the central committee which was to separate the children were

Armenians. Nezihe Hanim, General Secretary of the women's' branch of the Red

Crescent, had been invited to represent the Turks...When children were brought from

the orphanages in Anatolia to Istanbul, they were sent to the Armenian church in

Kumkapu, and there they were claimed to be Armenian. Some children tried to escape,

but were caught and brought back.

|

|

Halide

Edip |

It was a day when I had gone

to visit Nezihe Hallim. Two frightened children came into the room, one was limping

and the other had been wounded in the head... They had come from an orphanage and

had been brought to a church. They had strongly resisted being considered as

Armenians, as the Armenians had killed their parents. They had been severely beaten,

but had succeeded in escaping. They were crying, they were pleading to be protected,

not to be sent back... Nezihe Hanim called a few journalists and requested that they

be brought to Mr. Ryan, the head translator of the British Embassy... Although it

was known how much hatred he had against the Turks, Nezihe Hanim thought that he

would be compassionate in the presence of these two innocent and desperate children.

. . I later heard that when these two children were speaking, an Armenian official

entered the room to say something to Mr. Ryan. One of the children screamed this

was the man who beat and kicked us'. The man was a member of the delegation in the

Church of Kumkapu. . . . The pain of this little creature affected me very much. For

me he symbolized the desperate Turkish nation. He was small and weak. 393

The American Commissioner in Istanbul related the experience of an American

missionary at Sivas, Mary L. Graffam, on January 27,1919:

Reports received from Konia and elsewhere indicate that a

considerable proportion of Armenian girls taken into Turkish houses prefer to remain

there, and that even when they would like to leave they hesitate to make the step,

either because it would involve separation from their children or because they have

no way of earning a living.. For some reason or other all the girls and children in

Moslem houses take the same attitude as this girl and resist violently all efforts

of the relatives to take them away... ' Miss Graffam relates how she tried to get

the girl out of the house, but that the girl absolutely did not want to go.

394

|

| |

British Lieutenant J. A. Lorimer, reported to his superiors in Istanbul on a similar

situation in Konya. With the help of the local Turkish governor, he had been investigating

accusations that Armenian women and children were kidnapped and held against their will in

Turkish houses in the area. The Armenians locally had said that the girl in question,

Jamila, who was in the house of Arnaut Tahir Aga in the village of Veysehir, had

complained that her husband had forced her to marry him and stay in his family, and that

she had asked them to save her. Lorimer wrote:

This case seemed particularly promising as the Armenians had reported on

several occasions that this woman had written secretly to Armenians in Konia asking them

to save her, and that she dared not leave the house of Tahir, being afraid of the

consequences. They further reported that this man massacred this woman's father at

Erzeroum, stole all their money, and took possession of the girl. I asked the Vali to

imprison Tahir during the cross-examination so that she might have no fear from him. This

the Vali did without loss of time. On Saturday the first instant, this woman was brought

before the President of the Armenian Committee, an Armenian priest, myself and the Vali.

She was cross-questioned and declared that she wished to remain Islam and also that she

would not return to the Armenians under any conditions. Also that her father and mother

had been killed by Kurds and not by Tahir Agha. Thinking that she might be afraid of

speaking the truth before the Vali, I took her and the President into a separate room,

told her not to be frightened, etc., but she still remained of the same opinion, and in

fact became quite hysterical when it was suggested that she might be forced to return to

the Armenians. Suspecting that the Turks had sent a Turkish woman in Djemala's place, and

knowing of two Armenian women who personally knew Djemela, I asked them to identify her.

They both did so, so I stopped the case and allowed her to go free. Four other women were

then called forward, with the same result, saying that they had changed by the will of God

and had not been forced to do so. A small boy and girl, who also said that they were

Turks, I had sent round to the Armenian Orphanage, where they are now housed... 395

The Ottoman government ordered that Ottoman officials should do all possible to resist the

efforts of Allied missionaries and officials to force Armenian women to leave their Muslim

husbands and children even if they did not want to do so.396 It also responded directly to

the Armenian and Greek charges:

After the Armistice the Ottoman Government spent more than 1,150,000

liras, and employed hundreds of officials to return the Greeks and Armenians to their

previous areas of residence from the regions they had been transferred to. The procedures

involving the transfer of these people to their homelands, and returning to them their

movable and immovable properties, have been carried out through joint delegations formed

by British officers appointed by the British High Commission, Ottoman officials, and one

member of each of the interested nations. These delegations, whose number exceeded 62,

formed by British and Ottoman officials, which were sent to all parts of the country,

acted with the utmost attention and care. Even women who had married Muslim men of their

own accord were summoned one by one, and were asked again if they had consented, and those

who declared that they were pleased were left to their wishes. In the `harems' or

orphanages of Istanbul there were not hundreds of thousands of Armenian or Greek children

and women, there are not even two children who remained. While there are no remaining

Armenian children, some Muslim children, asserted to be Armenian, are still in Armenian

orphanages, even though their mothers and fathers are known to be alive. Then, how is it

possible that thousands of Armenian children, as it is claimed, are still in the presence

of Turks? How can the League of Nations, which does not have the legal character of an

executive power, and does not have an organization or the means to investigate the actual

situation in depth, conceive of the existence of children and women whom the police force,

the joint delegation, and the high officials of the Entente Powers in Istanbul were unable

to find?

For those who are somewhat aware of the actual situation, the matter is quite simple.

Because, if an American historian, who has been in Turkey for more than thirty years, and

who is at present a member of the Executive Committee of a Benevolent Society in Istanbul,

can try to find (only a week ago) a slave market in Istanbul where girls and women are

sold for money, then the report and speech reminding one of the Arabian Night Stories,

made by Mademoiselle Vakareski of Rumania, who does not know Turkey, who constantly looks

at Turkey from the perspective of the Armenians and the Greeks, and who is influenced by

their exaggeration of violence, must not be considered strange. How can it be explained

that this issue which has escaped the attention and the investigation of the officials,

the official and non-official organizations of the Great Entente Powers in Istanbul, was

able to be detected only by Mademoiselle Vakaresko who resides in Switzerland?

397

It was not only Muslims who were being forced into Christian families. There was

information that the local Papal delegate in Istanbul was gathering up all the refugee

Armenian and Greek Orthodox children he could find, classifying them as Catholics, and

sending them off to Catholic families.398

Many problems arose in the process of carrying out the orders to restore property which

had been abandoned, or sold at artificially low prices by Armenians and Greeks when they

were being deported during the war. Local officials were ordered to draw up detailed lists

of the property left by the deportees and refugees and the Muslim refugee families that

had been assigned to live and work in them. 399 All the properties of the returning

deportees had to be returned to them as son as they came back to their home towns. Most of

the homes and shops of the deportees or those who had fled the Empire had been turned over

Turkish refugees from Russia, the Caucasus and Southeastern Europe, but these were now

removed so that the original owners could be returned.400 This usually was done by direct

administrative procedures (idari karar) rather than by process of having a court

hearing to determine legal ownership and securing a court order for eviction, since such

procedures normally took many years,401 Many of the houses and churches had been left in

shambles and had to be cleaned up and repaired.402 All chandeliers which had been

transferred from churches to mosques had to be returned.403 In cases where the houses and

boats of deported Armenians and Greeks had been appropriated by businessmen and sold at

low prices to local Muslims, they had to be returned to their original owners without

compensation to those who had purchased them.404 If the original homes were not available

right away, the government had to pay for rented accommodations until permanent ones could

be found.405 The only properties that were not to be returned to their original owners or

their heirs were those which had been sold to pay prewar debts to the major banks and

foreign companies. Churches, schools and other properties of the non Muslim communities

which had been turned over to the Ministry of Religious Foundations for safekeeping after

their priests and teachers had been deported had to be returned to their communities

without delay.406 In many cases, the deportees had sold their properties to their churches

when they left during the war; these now were allowed to regain them, in contravention to

the normal Ottoman regulations which decreed that property once turned into foundations

could never be given back to private hands.407 Those institutions which had been used as

military hospitals or religious, civilian or military schools by the Ottomans were

evacuated and turned back to their owners.408 All the political rights of the deported

refugees were restored as soon as they returned to their homes, including not only the

right to vote, but also to hold office on the local, provincial and national level, with

several immediately rejoining local town administrative councils (meclis-i idare)

as well as all the Ottoman Chamber of Deputies on the basis of their election in the last

Parliamentary elections held before the war.409

In facilitating the resettlement of the refugees, however, particularly of the Armenians,

it soon became apparent that it was no longer possible for peoples who had lived together

for centuries to once again live side by side without conflict. Problems arose initially

when those refugees who returned found their homes had been turned over to Turkish and

Jewish families that had been deported from Greece, Bulgaria and Serbia, as well as

Armenia and Georgia, and who did not want to leave their new homes unless they also could

regain those from which they had been driven in Christian countries. Muslims throughout

Anatolia also had heard of the involvement of Armenians and Greeks in the Russian

invasions of eastern Anatolia as well as in the ongoing occupation of Turkish territory by

the victorious Allies, and were no longer willing to live with people whom they considered

to be traitors. They reacted angrily, moreover, to reports of the excesses committed

against Turks in Cilicia by Armenians who accompanied the French army. News that Greek and

Armenian raiders were attacking Turkish villages along the Aegean coast and that Greek

newspapers in Izmir and Istanbul were publishing violently anti-Turkish and anti-Muslim

stories and advocating that these territories be joined to Greece added to the Muslim

resentment and fears.410 Compounding the turmoil, many of the returning Armenians and

Greeks came to their former homes burning with desires for revenge against their former

neighbors, with the presence of the Allied occupation emboldening them to openly express

their long nurtured disparagement of Turks and Muslims which they long had concealed

during the centuries of Ottoman rule.411

|

|

The result of all this was explosive. Most residents of the towns in question were

unwilling to take back their former Christian neighbors under any circumstances,

particularly because of the fear that their presence would lead to the creation of

Christian states in which Muslims would be the persecuted minority, as had happened

in much of Southeastern Europe. There were constant fights between the Turkish

refugees and the Armenian and Greek refugees returning to their homes, and these

often spread to the entire communities on both sides, with the Ottoman efforts to

stop the turmoil completely unsuccessful.412 In many cases the Turkish refugees who

were forced to leave the homes in which they had been settled took all the

furnishings with them or destroyed them and sometimes even burned the homes as they

departed. They resisted with particular vehemence when attempts were made to force

them out of their homes into tents even before the returning owners arrived.413 In

other cases, they simply refused to leave, and the returning deportees used force to

reoccupy their old homes. Sometimes they did this on their own initiative, using

arms distributed to them by Armenian and Greek priests who traveled through Anatolia

under Allied protection on the pretext of inspecting the condition of churches.414

Sometimes they acted with the assistance of Allied control officers stationed in the

major towns and cities to supervise the resettlement. When their homes were found to

be derelict or destroyed, the latter helped them to forcibly evict Turkish and other

Muslim families in neighboring houses, even those who had deeds (tapu tezkere)

showing that the properties in question had been long held by themselves and their

families.415 When there were disputes regarding rights of ownership, the Allied

control officers invariably settled them in favor of the Christian claimants,

usually based entirely on their word because of the claim that their documents had

been destroyed during the war.416 When the Christian refugees complained about how

much food was being allocated to the Muslim refugees, Allied intervention soon

provided the former with much more than the latter, leading to even more resentment,

hatred and conflict.417 At times, [the] Ottoman government attempted to soothe over

such situations by renting temporary accommodations, either for the evicted Muslim

refugees or for the returning Christian deportees, but few houses were available,

and most had to live in tents, mostly exposed to the elements, leaving the quarrels

as devastating as they had been.418

Many of the people entering Anatolia as 'refugees,' moreover, turned out to be Greek

and Armenian immigrants from Russia, Egypt and elsewhere who had never lived there

before, but were being sent to Anatolia by nationalist groups in order to strengthen

their territorial claims based on population figures.419 The Ottoman government

repeatedly prohibited such practices, ordering its border guards to admit only those

who could produce documentation proving that they had lived in the Ottoman Empire

before the war, and to deliver such properties only to their original owners,

excluding those who were likely to disturb order or cause trouble.420 In practice,

however, it was almost impossible to enforce these restrictions, particularly for

large groups brought on Allied ships, who were admitted by the order of the Allied

military or control officers without the Ottoman officials being to intervene or

check their papers. The arrival at Izmit in March, 1919 of some two hundred Dashnak

fighters on a freighter hired by American Armenians who had brought them from

southern Russia, added to the chaos by letting them loose in a frenzy of killing

added to that already resulting from the constant raids of Armenian and Turkish

bands.421 Another Armenian Dashnak group was landed at Izmir in March 1919 and

attacked a large number of Muslim villages along the Aegean coast both before and

after the Greek invasion.422 In a few cases along the Black Sea coast, Armenians and

Greeks who could not reach their original distant homes settled in whatever Muslim

homes they wished in many cases with. the assistance of Allied soldiers and

policemen who were openly sympathetic to their co-religionists.423 Some returning

Armenians settled in the vacated homes of Greeks and vice versa, adding to the

turmoil. 424 Some of the returning Armenians, moreover, attacked Muslim travelers

while still on the road, stealing their money and their goods and in a few cases

murdering them in revenge for what had happened during World War I, adding to the

difficulties. 425

Of course the deported Armenians and Greeks were far from being the only refugees

who had to be cared for and relocated. There were Greek refugees from Thrace, and

Assyrians (Süryani-i Kadim), who had been deported from the war zones along

with the Armenians during World War 1.420 There were Ottoman nationals of all

religions, Christian, Jewish and Muslim alike, who had been employed as secretaries

(tercüman) and servants (kavass) of enemy embassies and consulates

before the war and who therefore had been thrown into jail when the first

mobilization began.427 There were Ottoman Greeks who had managed to take foreign

citizenship and who therefore had not been deported during the war, but who now

wanted to leave.428 There were Entente military officers and soldiers who had been

Ottoman prisoners and who now had to be freed in accordance with the Armistice

agreement, being sent to Istanbul or Izmir to be turned over to their own armed

forces.429 There also were the hundreds of German and Austrian subjects, including

quite a large number of Armenians and Greeks, who had been employed by the Ottoman

railroads and Public Debt Commission offices throughout the Empire, along with their

families, who were required by the Armistice to leave the Empire within a month.

After a time, however, a Mixed Allied and Ottoman commission based in Istanbul

allowed the companies that they worked for to retain their services on the grounds

that they could not be replaced. Rather than to return to an uncertain future in

their home countries, most of them renounced their old citizenships and become

Ottoman subjects in order to remain at their posts.430 The remainder were kept on

their jobs as long as possible, but finally starting in December 1918, most of those

working in Anatolia were moved to Adana and from there by train to Izmir, from which

ships took them to Bandlrma and then overland to Istanbul, from which they returned

to their home countries, with the expenses for transportation and food paid by the

Ottoman government only in cases of severe need.431 And, finally, there were

hundreds of 'enemy nationals,' citizens of Britain, France, Italy and Greece, who

had been held under house arrest during the war, unable to leave the Empire, most of

whom now were free to travel to the nearest port for transportation back to their

home countries.432

|

| |

There were almost a million Muslim refugees as well. There were thousands of Turks living

in tents around Anatolia, particularly in the Izmit peninsula, who had fled from the

Russian occupation of the three districts of Kars, Ardahan and Batum since 1878, the

devastating Russian invasion of Lazistan and the rest of northeastern Anatolia in 1916 and

1917, and the Armenian massacre of most Muslims living in Armenia.433 There were several

hundred Circassian refugees from the Georgians as well as the Armenians. There were

Chechen, Azeri, and Crimean Tatar refugees from the Russian occupation of their

homelands.434 There were approximately five thousand Ottoman prisoners remaining from

World War I who were wandering back from wartime prison camps in Russia and Egypt. There

were several hundred Ottoman students who had been studying and working in Germany and

Austria but who now were being deported from there by the victorious Allies. Some were

returning home, with the assistance of the International Red Cross, by every available

train running from Munich and Vienna to Bucharest, from which they were sent overland to

the Black Sea port of Kostence, and from there by ship to Istanbul, but others remained in

Europe and the Ottoman government was trying to find out where they were so they could be

helped to come home.435 Likewise students from Syria, Egypt and Iraq were attempting to

pass through Istanbul on their way home from their studies in Europe and America.436 There

were hundreds of Ottoman Muslims who during the war had been jailed in various communities

in north central Anatolia and along the Black Sea coast, but who had been brought together

at Cankiri in the spring of 1918. Those who had been at Kayseri. Nigde and Ankara had been

moved to Kochisar and those from Kütahya, Karahisar and Aydin to Isparta.437 There were

also Syrian and Medinan families who had been exiled to the areas of Trabzon, Kütahya,

Aydin and Adana during the war because of their involvement with Arab nationalist groups

or with the Arab revolt and who were now returned home at the expense of the Ottoman

government by sea to Beirut or by land to Aleppo, after which they traveled to their homes

at their own expense.438 There were Arab refugees from the British invasion of Syria and

Iraq and from French rule in Algeria and Tunisia and Bulgarian refugees who had fled to

Anatolia during the war, all of whom had to be given daily payments (yevmiye) and

to be housed and fed until they could be returned to their own countries.439 After a time,

however, the government stopped the payments to those Arabs who preferred to remain in

Anatolia indefinitely rather than returning to an uncertain future in their own

countries.440 There were Afghans and Indian Hindus and Muslims who wanted to go home. 441

Many of the Turkish prisoners of the Czars in Russia had been released at the outbreak of

the Bolshevik Revolution, but had been wandering around Siberia and Turkistan and becoming

[in]volved in Turkic nationalist movements which then were active in Buhara and Taskent

and elsewhere in Central Asia as well as in efforts of Cemal Pasa to build an army in

Afghanistan army and those of Mustafa Subhi to create a Turkish Communist Party and bring

Communism to Turkey. Those in Buhara had arranged for it to send large shipments of gold

to assist Mustafa Kemal and the Turkish nationalists, but since the shipments had been

sent through Moscow, it had been the Bolsheviks who took the credit.442 And, of course,

there were the thousands of Ottoman soldiers who had been suddenly demobilized by order of

the Allies without the Istanbul government having any means of transporting them back to

their homes. Most of these were crowded into railroad stations across Anatolia awaiting

transportation, in the meantime securing what housing and food that was available by

forceful means in the neighboring towns and villages, sometimes joining the National

Forces or operating their own robber bands throughout the countryside.443 Efforts to

resettle some of them on vacant farms with seed and tools provided by the government had

some success, but helped only a few out of thousands.444 The situation inevitably produced

constantly increasing hostility between the Muslim villagers, particularly in areas which

had suffered from the attacks of Armenian and Greek bands and of the Russian and Greek

armies, and the returning immigrants, who soon found that they no longer could fit into

the existing community life as they had done so well in preceding centuries. Turks

throughout Anatolia responded to what they considered to be an outrageous injustice by

applying the only weapon available to them at the start of the occupation: boycott of the

Christian merchants in their midst who were supporting the Allied intrusion which had

embolden[ed] them to openly show for the first time their long-suppressed hostility to the

Muslims whose leaders had ruled them since the fifteenth century.445 The boycott movement

was described by a British agent who traveled through central Anatolia in October, 1919,

describing the Muslim retaliation and the resulting Christian suffering without mentioning

the Greek and Armenian actions which caused people who had once lived together to become

mortal enemies:

I found everywhere that Greek refugees who had returned to Turkey since

the armistice have either left the country again or are on the point of doing so, in many

cases accompanied by Greeks who had remained in Turkey throughout the war. This exodus of

refugees is entirely due to complete lack of security in all villages, and to their being

unable to obtain possession of their properties, or to cultivate same with the knowledge

that they will be able to market the crops: also owing to the fear of further

persecutions....

4. Armenians in large parties (as many as eighty families in one party) have left for

Russia. and this movement threatens to become more general. Many communities (or the

remains of communities) informed me that they intended to leave the country at the first

opportunity.

|

Partial List of

Footnotes

|

337 Aksam no. 1341, 16 June 1922, no. 1347, 22June 1922 (with

photographs), no. 1354, 29 June 1922.

338 Conference of Ministers: minutes, 25 November 1920. Cabinet papers 23/23, quoted

in Gilbert, Churchill Companion IV/2, pp. 1252-1253.

339 Harbiye Nezareti lasi Müdüriyet-i Umumiyesi to Konya lase Murahhasl Mirliva

Esad Pasa, 20 Cemazi II 1336 / 2 April 1918: BBA DH/SFR, dosya 86, doc. 23; Harbiye

Nezareti Levazim-i Umumi Dairesi to governors of Ankara, Kastamonu, and Edirne and

other provinces, and district governors of Kütahya Eskisehir, Izmit, Bolu and other

districts, 24 Cemazi II 1336 / 6 April 1918: BBA DH/SFR, dosya 86, doc. 48; Asair ve

Mühacirin (Istanbul Dahiliye) to Governors of Beirut and Damascus and District

Governor of Beirut, 26 Cemazi II 1336 / 8 April 1918: BBA DH/SFR, dosya 86, doc. 76;

Asair ve Mühacirin (Istanbul Dahiliye) to Governors of Mamuretülaziz and

Diyarbekir, 26 Cemazi II 1336 / 8 April 1918: BBA DH/SFR, dosya 86, doc. 80; Asair

ve Muhacirin (Istanbul Dahiliye) to Governor of Bitlis, 28 Cemazi II 1336 / 10 April

1918: BBA DH/SFR, dosya 86, doc. 91; lase Nezareti, Muamelat-l Ticariye

Müdüriyet-i Umumi (Istanbul Dahiliye) to governors of Ankara and Eskisehir, 8

Safar 1337 / 13 November 1918: BBADH/SFR, dosya 93, doc. 152.

340 Ibrahim Edhem Atnur, 'Tehcirden Donen Rum ve Ermenilerin Emvalinin Iadesine Bir

Baksi,' Toplumsal Tarihi no. 9 (September 1994), pp. 45-48; Ibrahim Edhem

Atnur, 'Osmanh Hükümetleri ve Tehcir Edilen Rum ve Ermenilerin Yeniden Iskani

Meselesi,' Ankara Universitesi Turk Inklilap Tarihi Enstitüsü Dergisi no.

14 (November 1994), pp. 121-139. Asair ve Mühacirin to Governor of Karahisar-i

Sahib, 12 Cemazi II 1337 / 15 March 1919: BBA DH/SFR dosya 97, doc. 143; Asair ve

Mühacirin (Istanbul dahiliye) to governors of Erzurum, Trabzon, Van, Bitlis and

other provinces and district of Erzincan, 18 Rebi I 1337 / 22 December 1919: BBA

DH/SFR, dosya 94, doc. 204; Ibrahim Edhem Atnur, 'Tehcirden Donen Rum ve

Ermeniler'in Iskan Meselesi' (Unpublished Yüksek Lisans tezi, Atatürk University,

Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü, Erzurum, 1991).

Holdwater note: Transferring the footnotes was too much

work, so those of you who need to check these details will have to scrounge up a

copy of the book; sorry! Many derived from Ottoman archival sources as the last two

above. Below are a select few others.

375 Mary L. Graffam (Sivas) to American Commissioner (Istanbul) Louis

Heck, 27 January 1919, enclosed in Heck to Secretary of State no. 77, n d. (filed 25

February 1921): USDS Decimal File 867.4016/403.

390 Turkish intelligence report of 28 December 1922:CA (Ankara) BBK/30/10 kutu 108/dosya

7091doc. 7; Turkish intelligence report of 3 December 1922: CA (Ankara), BBK/30/10

kutu 206/dosya 406/doc. 5; Asair ve Mühacirin (Istanbul Dahiliye) to governors of

Edirne, Erzurum and Ankara, district governors of Canik, Catalca and Karesi, 19

Cemazi I 1337 / 20 February 1919: BBA DH/SFR, dosya 96, doc. 248; The procedures by

which this was done are described in: Calthorpe to Curzon no. 1491, 19 July 1919: FO

371/4196/3349/106070/44; Emniyet-i Umumiye (Istanbul Dahiliye) to governors of

Edirne, Erzurum. Adana and district governors of Urfa, Izmir and Bolu, 15 Rebi II

1337/ 18January 1919: BBADH/SFR dosya 95, doc. 163.

391 Vakit no. 661, 2 September 1919; Asair ve Mühacirin (Istanbul Dahiliye)

to Governor of Bitlis, 8 Cemazi II 1337/11 March 1919: BBA DH/SFR, dosya 97, doc.

104.

392 de Robeck to Curzon no. 1778/5018/12,27 September 1919: FO 371/4234/140455.

393 Halide Edib (Adivar), The Turkish Ordeal (London, 1928), pp. 16-18

394 Yeni Gazete, 15 January 1919. See also Mary L. Graffam, 'On the Road with

Exiled Armenians,' The Missionary Herald CXI (November 1915), pp. 565-568.

395 Enclosures in Admiral Richard Webb for High Commissioner, Constantinople, to

Foreign Office, 27 February 1919, no. 255:FO 371/4173/1270/42773 396 Kalem-i Mahsus

(Istanbul Dahiliye) to all provincial and district governors, 9 Saban 1337/10 May

1919: BBADH/SFR (Istanbul Dahiliye) dosya 99, no. 110.

397 Brochure of Ottoman Ministry of Interior in reply to League of Nations

accusations that there were thousands of Christian women forced into Muslim harems; Cemiyeti

akvam ve Turkiyedeki Ermeni ve Rumlar, Dahiliye Nezareti Muhacarin Kalem Md.

Nesriyat no. 6, Istanbul, 1922.

398 Sir W. Townley, The Hague, to Foreign Office, 16 November 1918: FO

371/3417/189916. The Armenian response was to ask the Allies to get the Papal

representative to send those children off to the Armenian Patriarchate in Istanbul

for care and education.

415 The conflicts that arose when returning Armenians and Greeks attempted to settle

in their old homes are described in hundreds of documents found in the archives of

the Ottoman Ministry of the Interior. Among them are: Emniyet-i Umumiye (Istanbul

Dahiliye) to Governor of Hüdavendigar (Bursa). 20 Muharrem 1337 / 4 November 1918:

BBADH/SFR, dosya 93, doc. 29; Emniyet-i Umumiye (Istanbul Dahiliye) to governors of

Edirne, Sivas, Adana and other provinces, and district governors of Urfa, Izmit,

Bolu and other districts, 29 Muharrem 1337 1 4 November 1918: BBADH/SFR, dosya 93,

doc. 31; [several other examples have been provided by Prof. Shaw.]

445 Details of the widespread Muslim boycotts of Christian shops throughout Anatolia

are found in Ottoman Ministry of the Interior (Istanbul Dahiliye) dossier dated 23

Cemazi II 1337 / 26 March 1919: BBADH/I-UM, dosya 19/5, doc. 1/48.

|

| |

|

|