|

|

The following are excerpts from the book:

"A Myth of Terror," by Eric Feigl

|

|

|

| A

Real Telegram by Talaat Pasha |

The Relocation Decision: Its Causes and Consequences

Armenians the world over remember April 24 as the day on which "the genocide of the

Armenians began". This memory should be reconsidered for a number of reasons. The day

of remembrance, April 24, intentionally confuses cause and effect.

The Ottoman minister of tile interior, Talaat Pasha, did indeed send a telegram on the

24th of April, 1915 ordering the arrest of the insurgents. There was still no talk,

however, of a relocation, since it was still not seen as necessary.

The coded telegram went to the governors of the provinces effected by Armenian subversion

and read as follows:

"Once again, especially at a time when tile state is engaged in

war, the most recent rebellions which have occurred in Zeitun, Bitlis, Sivas and Van have

demonstrated the continuing attempts of the Armenian committees to obtain, through their

revolutionary and political organizations, an independent administration for themselves in

Ottoman territory. These rebellions and tile decision of the Dashnak Committee, after the

outbreak of war, immediately to incite the Armenians in Russia against us, and to have the

Armenians in the Ottoman state rebel with all their force when the Ottoman army was at its

weakest, are all acts of treason which would affect the life and future of the country.

It has been demonstrated once again that the activities (it these committees, whose

headquarters are in foreign countries, and who maintain, even in their names, their

revolutionary attributes, are determined to gain autonomy by using every possible pretext

and means against tile Government. This has been established by the bombs which were found

in Kayseri, Sivas and other regions, also by the actions of the Armenian committee leaders

who have participated in the Russian attack on the country, by forming volunteer

regiment,, comprised of Ottoman Armenians in the Russian army, and through their

publications and operations aimed at threatening the Ottoman army from the rear.

Naturally, as the Ottoman Government will never condone the continuation of such

operations and attempts, which constitute a matter of life and death for itself, nor will

it legalize the existence of these committees which are the source of malice, it has felt

the necessity to promptly close down all such political organizations.

You are therefore ordered to close down immediately all branches, within your province, of

the Hinchak, Dashnak, and similar committees; to confiscate the files and documents found

in their branch headquarters, and ensure that they are neither lost nor destroyed; to

immediately arrest all the leaders and prominent members of the committees, together with

such other Armenians as are known by the Government to be dangerous; further, to gather up

those Armenians whose presence in one area is considered to be inappropriate, and to

transfer them to other parts of the province or sanjak, so as not to give them the

opportunity to engage in harmful acts; to begin the process of searching for hidden

weapons; and to maintain all contacts with the (military) commanders in order to be

prepared to meet any possible counter actions. As it has been determined in a meeting with

tile Acting Commander-in-Chief that all individuals arrested on the basis of files and

documents which come into our possession in the course of the proper execution of these

orders are to be turned over to the military courts, the above mentioned steps are to be

implemented immediately. We are to be informed subsequently as to the number of people

arrested, and with regard to the implementation of these orders.

For Bitlis, Erzurum, Sivas, Adana, Mara* and

Aleppo: as this operation is only intended to affect the operation of the committees, you

are strongly ordered not to implement it in such a manner as will cause mutual killings on

the part of the Muslim and Armenian elements of the population.

11. April 1331 (24. April 1915).

Minister of the Interior"

|

The rebels ...

completely destroyed the Moslem part of the city. Some 30,000 Moslems lost their lives

in the violence.

|

The arrests ordered on April 24 began the following day in Istanbul. In tile

provinces they began somewhat later in some cases. These arrests only affected the

ringleaders of the Dashnaktsutiun and the Hunchaks, along with a few well-known

agitators. The order had absolutely nothing to do with a general relocation.

The government's order to move the Armenians as a group out of the endangered areas

(Istanbul and Izmir were not affected since they were considered "safe"

and "under control") did not come until months later. It was brought on by

the horrifying assault of Armenian terrorists and irregulars on the city of Van.

This event represented a shocking climax of Armenian terrorism. The rebels conquered

Van, declared an "Armenian Republic of Van", and completely destroyed the

Moslem part of the city. Some 30,000 Moslems lost their lives in the violence.

|

|

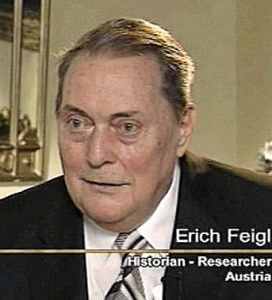

Prof.

Erich Feigl in the 2000s ("Sari Gelin")

|

Once again, the idea of moving the Armenian

population (and not just the terrorist ringleaders) out of the endangered areas did

not arise until after the catastrophe of Van. The government troops were forced by

the rebels to leave Van, on May 17, 1915. At this time, Van was behind Russian

lines, which were moving deeper and deeper into eastern Anatolia. The spearhead of

the Russian-Czarist assault troops was made up of Armenian volunteers, who

distinguished themselves with their particularly brutal treatment of the Moslem

population of eastern Anatolia. In the meantime, the true dimensions of the

catastrophe of Van became known in Istanbul. It was at this point that the idea

arose of relocating the Armenian population of Anatolia as a whole. Until this time,

there had only been arrests of ringleaders and known terrorists on a local level —

nothing more.

The concept of a relocation came up when the acting commander of the army, who had

learned his lesson from the horrid Outcome of the Van revolt, suggested responding

to steps taken by the Russians (which appear to have been discussed with the

Armenians!) with similar measures from the Ottoman side, This suggestion was made in

a secret communique of the Minister of the Interior (No. 2049):

The Armenians around tile periphery of Lake Van, and in other

regions which are known to the Governor of Van, are engaged in Continuous

preparations for revolution and rebellion. I am of the opinion that this population

should be removed from this area, and that this nest of rebellion be broken up.

According to information provided by the Commander of the Third Army, the Russians,

oil April the 7th (April the 20th), began expelling their Muslim population, by

pushing them, without their belongings, across Our borders. It is necessary, in

response to this (Russian) action, and in order to reach tile goals that I have

outlined above, either to expel the Armenians in question to Russia, or to relocate

them and their families in other regions of Anatolia. I request that tile most

suitable of these alternatives be chosen and implemented. If there is no objection,

I would prefer to expel the creators of these centres of rebellion and their

families outside our borders, and to replace them with the. Muslim refugees pushed

across our borders.

19. April, 1331 (2. May 1915).

The importance of this document lies in the fact that it clearly states what the

Supreme Military Commander's motive was. The Russians had sent the entire Moslem

population of the Caucasus region to eastern Anatolia, leaving them with nothing but

the shirts on their backs. At the same time, the Armenians in the eastern part of

the Ottoman Empire (particularly in Van) had siezed total power, killed the Moslems,

and proclaimed their "Armenian Republic of Van". Under these

circumstances, the decision to relocate the Armenians of Anatolia — those living

within the borders of the Ottoman Empire — is understandable. They were to be

moved "to areas considered safer", areas not so exposed to the grasp of

the Russians and the Allied powers of Europe.

(Holdwater: for a better

idea of the sequence of events, this May

2 telegram from Enver Pasha to Talat addresses the banishment of Russian

Moslems, and discusses the avenues for action: relocation or actual deportation, for

the Armenians.)

|

| To

try to place blame for a wartime tragedy such as this is truly senseless |

A few weeks later, on May 19,1331 June 1, 1915), the Ottoman

government published the following decree in the Takvimi Vakaya (the Ottoman official

gazette):

Article 1. In time of war, the Army, Army Corps, and

Divisional Commanders, their Deputies, and the Independent Commanders, are authorized and

compelled to crush in the most severe way, and to eradicate all signs of aggression and

resistance by military force, should they encounter any opposition, armed resistance and

aggression by the population, to operations and measures relating to orders issued by the

Government for the defense of the country and the maintenance of order.

Article 2. The Army, Army Corps, and Divisional Commanders are authorized to

transfer and relocate the populations of villages and towns, either individually or

collectively, in response to military needs, or in response to any signs of treachery or

betrayal.

Article 3. This provisional law will come into effect when it is published.

It is undoubtedly true that many innocent people lost their property, their health, and

even their lives in the relocation of 1915 — many Armenians and even more Moslems. To

try to place blame for a wartime tragedy such as this is truly senseless, but in light of

the almost universal assumption that everything was the fault of the "Terrible

Turks," something must be said about the passive behavior of the overwhelming

majority of Ottoman Armenians at the time. Above all else, they just wanted peace, and

they remained silent because they did not want a confrontation with the terrorists. For

decades, they tolerated the presence of a small number of fanatics among them who held

absurd, impracticable, and completely unjust ambitions for independence (unjust because

the Armenians did not have a majority anywhere in the Ottoman Empire). The extremists

became more and more Powerful; they terrorized Moslems and Armenians; and eventually,

after the beginning of the First World War," they were openly waging civil war.

In the turmoil of the war, with the Ottoman Empire forced to fight

for its very existence, there remained no other choice but to carry out the relocation.

The events that followed the end of the war — when the Allies penetrated into Anatolia

and the Greeks advanced almost as far as Ankara — prove just how wisely those

responsible for the relocation had acted.

If the "silent majority" of Ottoman Armenians had objected to

the insane plans of the extremists and the "romantic" visions of the

missionaries, many Armenians and even more Moslems would have been spared tremendous

suffering. As it was, however, many had to pay for the offenses of a minority.

Often — far too often — it is the success of the rational, level-headed majority in

prevailing over the irrational minority of agitators, fanatics, and romantics which

determines whether or not disaster will befall a nation.

A relocation camp ("Sari Gelin")

No nation that has let itself be seduced or silenced by a minority has ever been spared.

The National Socialists in Germany were also a minority, but they forced the majority of

peace-loving Germans into a world war. In the end, all Germans had to pay for that war —

with their property, their homes, their lives — whether they had been National

Socialists or not.

It would seem that the horrible thing about the history of the Armenians is that the

overwhelming majority of hardworking, intelligent, highly educated Armenians have let

themselves be manipulated, blackmailed, misled, and oppressed by a handful of fanatics

waging an irrational campaign of revenge. This majority silently ignores the acts of

terror of the "task forces" or "freedom fighters" or whatever else the

terrorists choose to call themselves. They fear for their property, their safety, their

lives. They give money to the terrorist groups without saying anything, and they act as if

nothing has happened when another bomb goes off, killing more innocent, respectable

citizens. it was no different before the First World War. Today, the myth of the genocide

has been added. This will have to suffice as a rationalization, even if the truth is

totally different.

|

The

fundamental message of Franz Werfel's novel — that those in charge within the

Ottoman government issued an extermination order — is false.

|

Franz Werfel's world-famous novel, The Forty

Days of Musa Dagh, is supposed to be a "modem saga of a persecuted

minority, determined to fight back". It is supposed to "snatch from the

Hades of all that was, this incomprehensible destiny of the Armenian nation".

The American edition of the novel was the basis for Werfel's worldwide fame.

According to the blurb on a German edition, the novel was seen not only by the

Armenians, but also by the Jews as "a simile for the Suffering of their

people". But the central, the fundamental message of Franz Werfel's novel —

that those in charge within the Ottoman government issued an extermination order —

is false.

In Werfel's version, the macabre scene between the Ottoman Minister of War, Enver

Pasha, and the Minister of the Interior, Talaat Pasha (who are portrayed as being

responsible for a genocide) reads as follows:

"A secretary brought in a sheaf of dispatches, which Talaat began to sign

without sitting down again. He did not look up has we was speaking: 'These Germans

are only afraid of the odium of being made partly responsible. But they may have to

come begging to us for more important things than Armenians,'

This might have ended that day's discussion of the banishment, had Enver's

inquisitive eyes not rested on the dispatches in casual scrutiny. Talaat Bey noticed

his glance and made the papers rustle as he waved them. 'The precise directions for

Aleppo. Meanwhile, I suppose, the roads will be clearer again. In the next few weeks

Aleppo, Alexandretta, Antioch, and the whole coast can begin to move out.'

‘Antioch and the coast?’ Enver repeated interrogatively, as though he might have

something to say on the point. He did not speak another syllable but stared

enthralled at Talaat's fat fingers, which, irresistible as a storming-party, kept

scribbling signatures under texts. These same forthright and stumpy fingers had

composed that order, sent out to all walis and mutessarifs: 'The goal of these

deportations is annihilation.' The short pen-strokes showed all the impetus of

complete, implacable conviction; they had no scruples.

|

|

Jemal

Pasha, before...

|

Jemal Pasha fares surprisingly well in Johannes

Lepsius' book Deutschland und Armenien (which Franz Werfel used extensively

in writing his "Forty Days"). This is reflected in an indirect statement

from Werfel concerning Jernal Pasha. At one point in his novel, the following is

said disparagingly about a zealous young Turk:

"One of the younger Mudirs went so far as to claim that Jernal Pasha, in spite

of his well-known role in the government, was not entirely reliable as concerns, the

Armenians and even made a deal with them in Adana."

Just how seriously the Armenian extremists take such statements is illustrated by

the fact that in the current American edition of the "Forty Days"

(published by Carroll & Graf Publishers, New York, by arrangement with Viking

Pengiun, Inc.), this passage has simply been dropped. A very meticulous proofreader

(or more accurately, censor) crossed out all the paragraphs in Werfel's novel that

approach objectivity. In the case of Jemal Pasha, it was apparently a matter of

justifying the murder of a man who did everything humanly possible for the

Armenians.

|

|

|

Jemal Pasha, after. Along with his young adjutant

(Yaver) Süreyya Bey, Jemal Pasha was murdered by the Armenians in Tiflis on

July 25, 1922, even though he had always helped them in every way possible

while he was serving as military commander of Syria.

|

The Armenian

forces interested in the fight against Turkey know the weak points in, Franz

Werfel's novel all too well. One such point occurs where the author strays into the

realm of historical facts. He meant well, but he was terribly careless in gathering

his data and thus had the uprising of Van breaking out 4fter the issuing ot the

relocation order.

Franz Werfel told it like this:

'The raison d'etat has never depended on making a graceful volt between cause and

effect. The bad, but lazy conscience of the world, the press of the respective

groups in power, and the minds of the readers, which the press has cut to size, have

always twisted and understood the issue as was required at that particular

time."

It is as if the censor who eliminated this passage from the English translation must

have meant to strike the next one, which is also missing:

"On the subject of Van, one could in certain circles write with indignation and

read with even more indignation: 'The Armenians have taken up arms against the

Ottoman Nation, which is involved in a burdensome war, and they have gone over to

the Russian side. The vilayets inhabited by Armenians must therefore be freed from

these people through deportation.'

Similar things could be read in the Turkish bulletins, but not the reverse, which

was the truth: 'The Armenians of Van and Urfa, in despair over the deportations,

which had been proceeding for a long time, defended themselves against the Turkish

military forces until they were relieved by the arrival of the Russians."'

|

|

It is certainly true that Franz Werfel, who

relied entirely on Armenian sources and a certain Johannes Lepsius in writing The

Forty Days of Musa Dagh, was convinced of the truth of what he wrote - that, the

uprising of Van was a reaction to a relocation order, a sort of desperate attempt at

self-defense.

The truth is just the opposite: the uprising was the prelude to a civil war

in the eastern province of Van and began in February of 1915 — almost two

months before the relocation order, which was a consequence of the

uprising of Van. In no way was the uprising of Van a "defensive reaction"

to the relocation order - that is really the truth turned on its head!

(Holdwater interruption:

The first rebellion

occurred in Van, days after Russia had declared war in November of 1914 —

almost six months before the end-of-May relocation order.)

The Armenian circles that shorten and mutilate Werfel's novel in the English edition

know exactly why they must take these passages — in this particular case a

whole page — out of the book. (There is, by the way, not one word to

indicate that the novel has been altered in this fashion.) Today, there are a few

scattered historical works in which anyone who is interested can find out about the

true events and the sequence in which they occurred. In some libraries, one can even

still find publications in which the Armenians boast of their war with the Ottomans,

although these publications have now disappeared from nearly all libraries, and it

has become truly difficult to find a magazine like Der Orient, put out by

Johannes Lepsius.

The Minister raised up his bent torso. 'That's done. In the autumn I shall be able

to say with perfect candour to all these people: >La question armenienne n'existe

pas.<"

With this choice of words, Franz Werfel anticipates almost prophetically the "Wannsee

Conference", where the leaders of the Third Reich — diabolical figures like

Himmler and Kaltenbrunner — agreed upon the extermination of the Jewish people.

The key scene in The Forty Days of Musa Dagh — the scene in which Enver

Pasha and Talaat Pasha decide on the extermination of the Armenians — is for many

people a sufficient rationalization for blind terror and savage acts of vengeance.

They ignore the fact that Franz Werfel's argumentation rests entirely on the forged

"documents" of Aram Andonian.

Werfel's novel is based on his personal knowledge, which he acquired from Armenian

contacts — undoubtedly in good faith. When he realized that he had been taken in

by forgeries, fear of Armenian reprisals kept him from acknowledging the truth. (We

will come later to the statement made on this subject by a Jewish friend of Franz Werfel.)

From ataa.org; Feigl's emphasis on words later added by Holdwater

|

| If history is to be examined,

one may observe that those who were living in the war regions hindered the actions of

the military units by protecting traitors and groups which acted together with the

enemy were sent away from the fronts. Another purpose of the transportation and

settling is to prevent the civilian people to suffer from war.

We see that some other states did also apply such obligatory

emigration practices, in the later years.

It is well known that the Alsaces, who lived in the

Franco-German border area, and spoke German, were taken away from the east of the

Maginot line in the winter of 1939-1940 and were transported to the southwest part of

France, especially to the Dordogne region by the Radical Socialist French Government.

Similarly, the American Administration had forced some of her citizens of Japanese

origin to emigrate from the Pacific region to the Mississippi Valley following the

Pearl Harbor attack and accommodated them in camps until the end of the war. (Acquaintances,

Oxford, U.P., 1967)

"Armenian Claims and Realities," Dr. Hüsamettin Yildirim,

Ankara, 2001, p. 38

|

A LESS COMPELLING EXAMPLE OF RELOCATION

AS A "MILITARY NECESSITY":

After the Pearl Harbor attack, anti-Japanese hysteria spread in the

government. One Congressman said: "I'm for catching every Japanese in America, Alaska

and Hawaii now and putting them in concentration camps. Damn them! Let's get rid of

them!"

Franklin D. Roosevelt did not share this frenzy, but he calmly signed Executive Order

9066, in February 1942, giving the army the power, without warrants or indictments or

hearings, to arrest every Japanese-American on the West Coast — 110,000 men, women, and

children — to take them from their homes, transport them to camps far into the interior,

and keep them there under prison conditions. Three-fourths of these were Nisei —

children born in the United States of Japanese parents and therefore American citizens.

The other fourth — the Issei, born in Japan — were barred by law from becoming

citizens. In 1944 the Supreme Court upheld the forced evacuation on the grounds of military

necessity. The Japanese remained in those camps for over three years.

Holdwater: But even with this outrage —

unlike the Ottoman-Armenians who had wholly joined the Entente Powers and were

"belligerents de facto," in Boghos Nubar's words, Japanese-Americans were not

disloyal — the young men of this community made a point of serving in the United States

military to demonstrate their affinity to their country.

Thanks to reader Conan for the above excerpt, from this site.

|

|