|

|

On this page we'll take a look at

the peculiarities of Ambassador Henry Morgenthau's "Story" book.

This is the terribly racist book that

Prof. Roger Smith actually referred to as reliable history in an April 2005

"genocide" conference held in New York's Fordham University. Let's

give just one example of the delights within this literary

"masterpiece":

"One day I was discussing these proceedings with a

responsible Turkish official, who was describing the tortures inflicted. He

made no secret of the fact that the Government had instigated them, and, like

an Turks of the official classes, he enthusiastically approved this treatment

of the detested race. This official told me that all these details were

matters of nightly discussion at the headquarters of the Union and Progress

Committee. Each new method of inflicting pain was hailed as a splendid

discovery, and the regular attendants were constantly ransacking their brains

in the effort to devise some new torment. He told me that they even delved

into the records of the Spanish Inquisition and other historic institutions of

torture and adopted all the suggestions found there. He did not tell me who

carried off the prize in this gruesome competition, but common reputation

throughout Armenia gave a preeminent infamy to Djevdet Bey, the Vali of Van,

whose activities in that section I have already described. All through this

country Djevdet was generally known as the "horseshoer of Bashkale"

for this connoisseur in torture had invented what was perhaps the masterpiece

of all — that of nailing horseshoes to the feet of his Armenian

victims." (Chapter XXIV, page 307)

Ever notice the absence of names in

testimony as the above? Who was this "responsible Turkish official,"

and why would he have been so open about discussing internal matters with a

hostile foreign agent? Secondly, if he "enthusiastically approved"

the described tortures, why would that have made him "responsible"?

Thirdly, is this what a courtroom of law or conscience of a good human being

would call, "hearsay"?

Ambassador Morgenthau attempted to make

the Turks as monstrous as possible. The attorney-ambassador allowed his

Armenian assistants significant output, and his motives for demonization have

been examined elsewhere in the site. (See links at page bottom.) But for

Morgenthau to have written such fabricated material as the above was truly

unconscionable. What kind of a man would be so bereft of morals to record such

defamatory and horrible lies, as if they actually had taken place?

And what kind of man would be so bereft

of morals as to repeat these disgusting stories in this day and age, as Peter Balakian gleefully did at every

opportunity in his "Burning Tigris" abomination? (Mr.

Balakian pointed to this horseshoe-nailing

business above, among so many others.)

|

|

|

| Prof.

Sidney Fay, 1925: "Hardly a word of truth" |

Excerpted from:

Harry E. Barnes, Genesis of the World War (New York: Knopf, 1926), pp. 241-247:

[begin quote]:

This luxuriant and voluptuous legend was not only the chief point in the Allied propaganda

against Germany after the publication of Mr. Morgenthau’s book, but it has also been

tacitly accepted by Mr. Asquith in his apology, and solemnly repeated by Bourgeois and

Pages in the standard conventional French work, both published since the facts have been

available which demonstrate that the above tale is a complete fabrication. The myth has

been subjected to withering criticism by Professor Sidney B. Fay in the Kriegschuldfrage

for May, 1925:

|

|

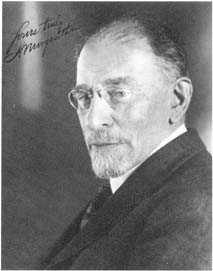

From His

"Truly," Henry Morgenthau

|

The contemporary documents now available prove conclusively that there

is hardly a word of truth in Mr. Morgenthau’s assertions, either as to (a) the

persons present, (b) the Kaiser’s attitude toward delay, (c) the real reasons for delay,

or (d) the alleged selling of securities in anticipation of war. In fact his assertions

are rather the direct opposite of the truth.

a) As to the persons present, it is certainly not true that “Nearly all the important

ambassadors attended.” They were all at their posts with the exception of Wangenheim,

himself, and it is not certain that he even saw the Kaiser. Moltke was away taking a cure

at Karlsbad, and Tirpitz was on a vacation in Switzerland. Jagow was also in Switzerland

on a honey-moon and did not return until July 6. Ballin, the head of the Hamburg-American

Line, who was absent from Berlin in the early part of July at a health resort, does not

appear to have had any information until July 20, that there was a possible danger of

warlike complications. Krupp v. Bohlen-Halbach, the head of the great munition works, was

not at Potsdam on July 5, but saw the Emperor William next day at Kiel as the Emperor was

departing for his Northern cruise. Nor is there any evidence that they were gathered at

Potsdam on July 5 any of the others who were “necessary to German war preparations.”

The only persons with whom the Kaiser conferred on July 5, at Potsdam after his lunch with

the Austrian Ambassador, were Bethmann-Hollweg, the Chancellor, Falkenhayn, the Prussian

Minister of War, and certain routine subordinate officials.

b) It is certainly not true that the Kaiser wished Austria to delay for two weeks whatever

action she thought she must take against Serbia in order to give the German Bankers time

to sell their foreign securities. There is abundant proof to indicate that Emperor William

wished Austria to act quickly while the sentiment of Europe, shocked by the horrible crime

at Sarajevo, was still in sympathy with the Habsburgs and indignant at regicide Serbs. As

he wrote in a marginal note, "Matters must be cleared up with the Serbs, and that

soon."

c) The real reasons for the delay of two weeks between July 5 and 23, was not to give the

German bankers two weeks to sell their foreign securities. The real reasons for delay were

wholly due to Austria, and not to Germany. They were mainly two, and are repeatedly

referred to in the German and Austrian documents which were published in 1919. The first

was that Berchtold, the Austro-Hungarian Minister of Foreign Affairs, could not act

against Serbia until he had secured the consent of Tisza, the Premier of Hungary. It took

two weeks to win Tisza over from his original attitude of opposition to violent action

against Serbia. The second, and by far the most important reason for the final delay, was

the fact that Berchtold did not want to present the ultimatum to Serbia until it was

certain that Poincaré and Viviani had left Petrograd and were inaccessible upon the high

seas returning to France. For otherwise Russia, under the influence of the “champagne

mood” of the Franco-Russian toasts and the chauvinism of Poincaré, Iswolski, and the

Grand Duke Nicholas gathered at Petrograd, would be much more likely to intervene to

support Serbia with military force, and so Austria’s action against Serbia would less

easily be "localized."

d) In regard to Germany’s alleged selling of securities in anticipation of war, if one

follows Mr. Morgenthau’s suggestion and examines the quotations on the New York Stock

Exchange during these weeks, and reads the accompanying articles in the New York Times,

one does not find a shred of evidence, either in the price of stocks or the volume of

sales, that large blocks of German holdings were being secretly unloaded and depressing

the New York market during these two weeks. The stocks that he mentioned declined only

slightly or not at all; moreover, such declines as did take place were only such as were

to be naturally expected from the general trend downward which had been taking place since

January, or are quite satisfactorily explained by local American conditions, such as the

publication of an adverse report of the Interstate Commerce Commission. Here are the

facts. The amazing slump in Union Pacific from 155 ½ to 127 ½ reported by Mr. Morgenthau

represented in fact an actual rise of a couple of points in the value of this stock. Union

Pacific sold “ex-dividend” and “ex-rights” on July 20; the dividend and

accompanying rights were worth 30 5/8, which meant that shares ought to have sold on July

22nd at 125 ¾. In reality they sold at 127 ½; that is, at the end of the two weeks”

period which it is asserted that there was “inside selling” from Berlin, Union

Pacific, instead of being depressed, was actually selling two points higher.

Baltimore and Ohio, Canadian Pacific, and Northern Pacific did in fact slump on July 14,

and there was evidence of selling orders from Europe. But this is to be explained, partly

by the fact that Baltimore and Ohio had been already falling steadily since January, and

partly to the very depressing influence exercised on all railroad shares by the sharply

adverse report on the New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad, which was published by

the Interstate Commerce Commission. The comment of the New York Times of July 15, is

significant: "Stocks which have lately displayed a stable character in the face of

great weakness of particular issues could not stand up under such selling as occurred in

New Haven and some others today. There were times when it looked as though the entire

market was in a fair way to slump heavily, and only brisk short covering toward the close

prevented many sharp net declines. For its own account, or on orders from this side,

Europe was an unusually large seller of stocks in this market. The cable told that a very

unfavorable impression had been created by the Commerce Commission’s New Haven report.

The European attitude toward American securities is naturally affected by such official

denunciations of the way in which an important railway property has been handled."

Most extraordinary is Mr. Morgenthau’s assertion about United States Steel Common. He

says that between July 5th and 22nd it fell from 61 to 51 ½. The real fact, as any one

may verify from the Stock Market reports for himself, is that Steel during these two weeks

never fell below 59 5/8, and on July 22nd was almost exactly the same as two weeks

earlier.

When the facts are examined, therefore, it does not appear that the New York Stock Market

can afford much confirmation to Mr. Morgenthau’s myth of German bankers demanding a two

weeks respite in which to turn American securities into gold in preparation for a world

war which they had already plotted to bring about.

As Mr. Morgenthau has persistently refused to offer any explanation or justification of

his "story" or to answer written inquiries as to his grounds for believing it

authentic, we are left to pure conjecture in the circumstances. It appears highly doubtful

to the present writer that Mr. Morgenthau ever heard of the Potsdam legend while resident

in Turkey. It would seem inconceivable that he could have withheld such important

information for nearly four years. The present writer has been directly informed by the

Kaiser that Wangenheim did not see him in July, 1914. We know that Mr. Morgenthau’s book

was not written by himself, but by Mr. Burton J. Hendrick, who later distinguished himself

as the editor of the Page letters. We shall await with interest Mr. Hendrick’s

explanation of the genesis of the Potsdam fiction as it was composed for Ambassador

Morgenthau’s Story.

[end quote]

Holdwater: It sure would have been great if

Burton Hendrick had been cornered during the 1920s to explain himself. But the immoral

ghostwriter had a huge slice of the profit-sharing pie, as Prof. Heath Lowry exposed, and

it would have been doubtful that Hendrick would have come clean.

You'll note not a word was wasted on Morgenthau's

treatment of the Turks, in the criticism above. (As Pauline Kael aptly noted in her film

review of MIDNIGHT EXPRESS, "Who

wants to defend Turks?" This was true in 1978, as it was true in 1925, and still

true today.)

But I think that's just as well. The reader can get

an excellent idea as to Henry Morgenthau's penchant for truth-telling, regarding other

matters of history, and the sale of securities. And to think this is the man whom Prof.

Levon Marashlian defended, telling us Morgenthau's testimony was "unimpeachable."

Thanks to Conan, and to this site.

Mustafa Artun

Opinion, May 2003, The Turkish Times

|

|

Peter

Balakian edited the reissue |

Of all the books used by the Armenian propagandists and their sympathizers to

vilify Turkey, arguably the most often-quoted is Ambassador Morgenthau's Story by

Henry Morgenthau who served as the American ambassador in Istanbul for twenty-six months

from 1913 to 1916. First published in 1918, the book has been reprinted numerous times

over the years. A new edition, edited by a leading Armenian propagandist, Peter Balakian,

is being published this year with good deal of publicity fanfare. The book has been a

standard reference for most of the so-called "scholarly" publications as well as

journal and newspaper articles on the subject. The latest addition to the long list of

publications that have utilized Ambassador Morgenthau's Story as if it were an objective

and factual account of the events in 1915 is Samantha Power's A Problem From Hell:

America in the Age of Genocide which won the prestigious Pulitzer Prize in 2003. In

her book, Power portrays Morgenthau as a heroic figure who strove to stop the killing of

the innocent Armenians at the hands of the Ottoman Turks. Equally important is the fact

that whenever a resolution to condemn Turkey is introduced in state legislatures or at the

U.S. Congress, Morgenthau's book is presented as prima facie evidence in support of the

Armenian claims.

|

|

Samantha

Power; a lawyer, like her

hero, Henry Morgenthau |

That Ambassador Morgenthau's Story has been a powerful

arsenal in the Armenian propaganda machine against Turkey in the U.S. is not surprising.

After all, Morgenthau was appointed by President Wilson to be the official representative

of this country in the Ottoman Empire. Ambassadors are normally expected to provide

factual, honest, and unbiased reporting about the countries where they serve.

Consequently, Ambassador Morgenthau's book, which seeks to indict the Young Turk

leadership of having engaged in a systematic campaign of violence against the Armenians,

carries the official stamp of credibility. What makes the book even more enticing for

those who seek to slander Turkey is that Morgenthau's "story" includes lengthy

passages about the author's alleged conversations with the leading Young Turk officials

such as Talat Pasha where they confess their plans to annihilate the Armenians to the

American Ambassador.

Although Morgenthau's book is widely quoted and used as an important and reliable source

on the Armenian question, few seem to take notice its blatantly racist contents. In fact, Ambassador

Morgenthau's Story is littered with the most appalling and demeaning characterizations

of the Turks, their history and culture. For Morgenthau, the Turk is "psychologically

primitive" (p.236) and a "bully and a coward" who can be "brave

as a lion when things are going his way, but cringing, abject, and nerveless when reverses

are overwhelming him" (p. 275)*. According to the Ambassador, the Turks "like

most primitive peoples, wear their emotions on the surface" (p.195) and that the "basic

fact underlying the Turkish mentality is its utter contempt for other races" (p.

276). Morgenthau describes the Turks variously as "inarticulate, ignorant, and

poverty-ridden slaves" (p. 13), "barbarous" (p.147), "brutal"

(p.149), "ragged and unkempt" (p. 276), and "parasites"

(p.280). The Ambassador's unabashed hatred of all things Turkish leads him to make the

following observation: "The descendants of Osman hardly resemble any people I have

ever known. They do not hate, they do not love; they have no lasting animosities or

affections. They only fear" (p.99).

Morgenthau's view of Turkish history and the treatment of non-Muslim communities in the

Ottoman Empire offer further glimpses into his distorted and biased mindset. He notes, for

example, "after five hundred years' of close contact with European civilization,

the Turk remained precisely the same individual as the one who had emerged from the

steppes of Asia in the Middle Ages" (p. 284). According to the author, when Turks

conquered a territory, they "found it occupied by a certain number of camels,

horses, buffaloes, dogs, swine, and human beings. Of all these living things the object

that physically most resembled themselves they regarded as the least important"

(p. 279). Even the millet system, long regarded by most historians as an important

mechanism for peaceful coexistence among different ethnic and religious groups in the

Ottoman Empire, does not escape the Ambassador's wrath: "The sultans similarly

erected the several peoples" he writes "such as the Greeks and the

Armenians into separate 'millets' or nations, not because they desired to promote their

independence and welfare, but because they regarded them as vermin" (p. 280). In

contrast to his utter disdain for the Turks, Morgenthau has nothing but praise for the

Armenians. "The Armenians," he writes, "are known for their

industry, their intelligence, and their decent and orderly lives. They are so superior to

the Turks intellectually and morally" (p. 287). According to the author, the

Armenians lived like "a little island of Christians surrounded by backward peoples

of hostile religion and hostile race" (p. 288). And the Ambassador

enthusiastically declares that like the Arabs who had revolted against the Ottomans in

World War I, the Greeks and the Armenians "would also have welcomed an opportunity

to strengthen the hands of the Allies" (p.227). Ambassador Morgenthau's Story

stands as one of the remarkable documents of early 20th century — not for its value as

an objective piece of historical writing, as the Armenian propagandists and their

supporters claim, but for revealing the deep-rooted racist outlook of a person who managed

to reach one of the highest and most prestigious positions in the U.S. government. It is

telling that at a time when racism has become punishable by law in this country, a book

that is filled with appalling racist remarks continues to be glorified in the American

academia, intellectual circles, and legislative bodies by Armenians and their sympathizers

determined to distort history and slander the Turks at any cost.

*All the quotes are from Henry Morgenthau, Ambassador Morgenthau's Story (New York:

Doubleday, Page and Company, 1918).

Ambassador

Henry Morgenthau

The Story

Behind Ambassador Morgenthau's Story

Another reason for Mr. Morgenthau's ways involved his

commitment to Zionism and the creation of a Jewish state:

"The Burning Tigris" Critique; Chapter 17 on Henry Morgenthau

|

|