|

|

The Destruction of Ottoman

Erzurum by Armenians

Presented during a Conference by Erzurum, Ataturk

University, September 2002

by Prof. Justin McCarthy

I am very pleased to

be in Erzurum today. I am especially glad to be among my colleagues, the

professors of Atatürk University, who have done so much to investigate the

massacres of the Turks of Erzurum and to teach us the story of the saddest

period in Turkish history.

(Holdwater's

Reflections follow.)

|

|

|

| Life, Disorder,

and Conflict in Erzurum Province |

Before considering their

history, it is essential to first identify the people of Ottoman Erzurum Vilâyeti.

Armenians often claimed Erzurum,

but in 1914 no Armenian had ruled Erzurum for more than 900 years. More important, the

population of Erzurum was solidly Muslim. There were five times as many Muslims as

Armenians in the province. Early in the nineteenth century the percentage of Armenians had

been somewhat larger and the percentage of Muslims somewhat smaller. But Erzurum had not

had an Armenian majority for many centuries. In Ottoman times, Erzurum had always been at

least two-thirds Muslim.

(I say "Muslim" rather

than "Turk", because the Ottomans kept all their population records by religion.

Anyone who says he knows precisely the ethnicity or language of the inhabitants of the

Ottoman Empire is inventing his statistics. All evidence indicates, however, that the

majority of Erzurum's Muslims were Turks.)

Erzurum in 1912

|

Community

|

Population

|

Percent

|

|

Muslim

|

804,400

|

83%

|

|

Greek

|

5,800

|

*

|

|

Armenian

|

163,200

|

17%

|

|

Other

|

800

|

*

|

|

Total

|

974,200

|

|

* less than 1%

|

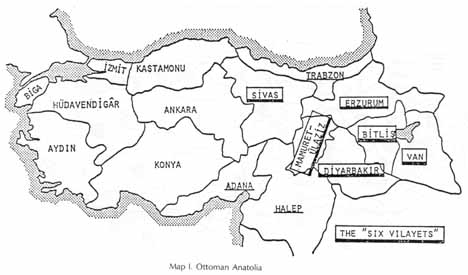

Just to give you an idea where "Erzurum"

is.

|

Now to the Armenians of Erzurum. For

many years, Americans and Europeans have been told that the Armenians were

persecuted. Is this true? It is not. Some Armenians did indeed suffer, but what they

suffered was not persecution.

Life was

indeed hard for the Armenians of Erzurum. They did not live as comfortably or as

safely as the Armenians in Western Anatolia or Istanbul. They were often poor;

making a living by farming land that could barely support their families. They were

sometimes in danger, robbed by Kurdish tribes or bandits. The government could not

protect them properly. Sometimes the government officials who should have protected

them instead took advantage of them.

The life of

the Armenians was indeed hard, but they were not alone. The life of Erzurum's

Muslims, including the Turks and the peaceful Kurds of villages and cities, was just

as difficult. They too were poor. They too were robbed and killed. They too went

unprotected.

The fact

that all the people of Erzurum suffered alike is often hidden from the world. That

is due to the reporting of missionaries and foreign diplomats. Most of the Europeans

and Americans tended to report only the murders of Armenians, not the murders of

Muslims. They sent reports of robberies of Armenians, not of robberies of Muslims.

Luckily, some Europeans, especially certain British consuls, and the Ottomans

themselves kept records of what was really happening in Eastern Anatolia.

There is

little time here for examples of the difficulties of life in Erzurum, but one of the

best examples is the career of Hüseyin A?a.

Charles

Hampson, one of the many British consuls who served in Erzurum, was no friend of the

Turks, but he occasionally simply reported what occurred. In 1891 he sent a report

on the activities of Hüseyin A?a, a sub-chief of the Haydaranl? Kurds in Ele?kirt.

Hüseyin had plundered another Kurdish village, carrying off all their sheep. He

murdered the Muslim religious leader of Patnos, ?eyh Nuri. Then he burned down nine

villages, tortured and murdered the Muslim inhabitants, and carried off their sheep

and other animals. He was accused of murder, robbery, extortion, and rape by Muslims

and Christians alike. All, no matter their religion, suffered at his hands. Finally,

with great difficulty, he was caught and held in Erzurum.

While Hüseyin was being held, his brother and son took over the family's work and

robbed twenty-one more villages.

Hüseyin

was reported to command 2,000 men. This may have been an exaggeration, but one can

see why the government had great difficulty in controlling him.

Hüseyin

was only one of the tribesmen who disrupted the life of the settled population of

Erzurum. Erzurum Province was a place of insecurity. In 1893, the caravan from

Erzurum to Bitlis was attacked by Kurds before it had gone five miles from the city.

The inspector of the Tobacco Regie was robbed by Kurds in 1892. Both Armenian and

Armenian merchants protested that they could not trade because of the actions of

bandits. The Muslim merchants of Erzurum formerly complained to the government in

Istanbul of the insecurity in the province. They said the Kurdish tribes were

attacking Turks and Armenians alike.

|

| |

Why was Erzurum unsafe for both Muslims and

Christians? It was not the Ottoman administrators or the Ottoman system. Some valis

were good, some bad. Most seem to have done as well as they could with the resources they

had. Even the Europeans praised some governors as well-intentioned and energetic men. The

problem was that they had so few resources. What was needed in Erzurum was money. The

gendarmes were often not paid even their small salaries. Officials too went unpaid. Money

was needed to hire more police, soldiers, and officials. Money was also needed for seed,

fertilizer, better roads, and all the things that would have made Erzurum a better place.

But there was no money.

Who was to blame for the poverty

of Erzurum? Partly it was the Ottoman Government. The Ottomans were never good

accountants. But the main cause of Ottoman weakness was beyond Ottoman control. The

Russians had damaged the Ottoman Empire both militarily and economically in the 1877-78

war. In addition to the loss of manpower, supplies, and productive territory, the Ottomans

had been forced to pay a crushing indemnity of 800 million francs. Then the Empire was

forced to spend great amounts to defend against the next Russian attack. The Ottomans were

forced to spend ten times as much on the military as on the police and gendarmery, and

twenty times as much on the military as on education. The "friends" of the

Ottomans only worsened the economic state by enforcing the capitulations. No wonder the

gendarmes could not be paid.

The Ottomans did what they could

to make Erzurum more secure for both Armenians and Muslims. 51 Armenians were actually

enrolled as gendarmes in Erzurum Province in 1896, braving the opposition of the Armenian

revolutionaries. The vali wanted 218, but no more could be found, because the pay was so

irregular. Even the most loyal Armenian subject of the sultan had to feed his family.

It would be absurd to think that

the Ottoman Government approved or fostered the state of unrest in Erzurum and elsewhere

in Eastern Anatolia. There is no evidence that the Government held any animosity toward

its Armenian subjects, but one need not assume governmental good will, only self-interest.

The Government needed money. The only way to obtain the money was from taxes. The only way

to increase taxes was to increase production, and that demanded improved security.

Security for all, Muslims and Armenians, would have been good for the government.

The question of whom

suffered more from attacks by tribes and bandits, the Muslims or the Armenians cannot be

answered. Neither can one say whether Muslim farmers or Christian farmers were better off.

Both Armenians and Turks complained

of Kurdish raids. Neither was doing very well.

It is known that in some

respects the Armenians were in a much better position than the Muslims. In the cities and

towns the Armenians were wealthier and had more economic and social opportunity. This was

true all over the Ottoman Empire.

Nowhere was the superior

situation of the Armenians more evident than in education. In 1881 there was only one

public secondary school for Muslims in the city of Erzurum, with 120 students. The

students, all boys, had few textbooks and no maps. Sixty-five Muslims were enrolled in a

better private school. Another 1,500 Muslim students were enrolled in one form of

elementary school or another. Altogether, approximately ten per cent of the Muslim boys of

Erzurum City attended school. 70% of the Armenian children, boys and girls, attended

school. Each of the three Armenian millets--Gregorian, Catholic, and Protestant

(American missionary), had its schools. They were well equipped, especially when compared

to what was available for the Muslims. The primary cause for the difference between Muslim and Armenian education was

obviously money. The Armenians could afford to pay for their education, and the American

missionary schools were supported by donations from the United States.

Armenians, not Muslims, could

expect help from Europeans. Armenians who were beset by Kurdish tribes or over-zealous tax

collectors could rely on European consuls to advance their cause to local officials. This

was a privilege seldom afforded to Muslims.

The Armenians also benefited

because they could escape. Armenians were constantly leaving the Erzurum Province during

the final Ottoman decades. Approximately 1,000 a year went to the Russian Empire. The

Ottoman Administration frowned on this migration, but it could not stop it. Armenian men

and sometimes families often traveled to Istanbul for work or as permanent migrants. Some

went to America.

Did these migrants leave for

political reasons? It is doubtful if that was ever a prime motivation. They left for

understandable economic reasons. There were jobs and a better life in Istanbul, Erivan,

and America. In each place, Armenians had support systems and charities that helped them

get started in new lives.

Why did the Muslims, even more

poor than the Armenians, not leave Erzurum as well? There were no such support systems for

them. They were not welcome in America. The American Christian churches that sent

missionaries to the Ottoman Empire also aided Armenians who went to America. They did not

assist Muslims. Except for some skilled workers, Russia surely did not want more Muslim

immigrants. And what would Erzurum's Muslims do in Istanbul? Turks from Anatolia did

routinely go to Istanbul for work, and had been doing so for quite some time. But those

Turks, primarily from regions close to Istanbul and from the Black Sea provinces, had

support groups--villagers who had gone before them and helped new migrants. Those support

groups were not there for Erzurum Muslims.

|

What Drove the Armenian and Muslim

Communities Apart?

|

All was not

animosity between the Muslim and Armenian communities. The two communities had lived

side by side for nearly 900 years. Merchants and craftsmen had natural business

connections. In at least one incident, Muslim merchants contributed to a collection

for destitute Armenians. Armenian leaders often had good relations with Ottoman

officials. But many factors worked to drive the two communities apart. In times of

famine in the 1870s and 1890s, for example, American missionaries distributed relief

to the Armenians, but seldom or not at all to the Muslims. It was common for

European consuls and American missionaries to write words such as, "Great

distress is actually prevailing throughout the whole of Kurdistan. At Kharpout this

almost amounts to famine. While at Bitlis, Van, and Erzeroum great poverty

exists," then to ask that aid be sent for the Christians alone! The famine and

poverty of the Muslims were not their concern. All this cannot have helped

inter-faith brotherhood.

The schools provided to

the Christians by the Armenian Church and the Americans gradually led to an Armenian

populace that was better educated and more able to cope with the modern world. This

caused both Muslim resentment and a sense of superiority among the Armenians.

The psychological climate

engendered by the relative educational superiority of the Armenians, by the

favoritism showed them by Westerners, and by the promises of revolutionaries that

Armenians would soon rule cannot be quantified. One British observer, the consul at

Erzurum, made an attempt at a description. (It must be remembered that the British

did not easily criticize Armenians.)

The Armenians seem to possess in an eminent degree the

art of making enemies, and competent observers are of opinion that a notable

demoralization of the national character in these regions was produced by the lavish

distribution of relief after the massacres of 1896. This decadence has been still

further accentuated since the restoration of the Constitution and mainly by the

pernicious influence of the Tashnakists and the Armenian refugees from the Caucasus.

Immorality and drunkenness prevail among the Armenians of this district to an extent

which would surprise the readers of British pro-Armenian literature, and even in the

principal Armenian school of Erzurum, which is under the chairmanship of the Bishop,

the doctrines of socialism and "free-love" are openly taught. The outcome

of this state of things is a growing insolence on the part of the Armenians which is

remarked on by all travellers and is assuredly not unnoticed by the Moslems,

irritated as the latter already are by the efforts of the Tashnakists to acclimatize

the tenets and outward manifestations of Western socialism; . . .

What had led to such a

state? It was not acts of the Ottoman Government that drove the Muslims and

Armenians apart. Despite all the problems of Erzurum Province, the Muslims and

Armenians had lived together under that government and under the same basic social

and economic system for nearly 400 years. It was acts of the Russians and the

Armenian Revolutionaries that finally split the communities and ultimately destroyed

Ottoman Erzurum.

|

| The Russians |

The Russians began to suborn the loyalties of

Armenians in the 1790s. They depended on Armenians as spies and even troops when

they conquered Azerbaijan and Erivan. They encouraged the Armenians to move to

territory the Russians had conquered, offering them incentives to do so.

In 1878, 25,000

Anatolian Armenians migrated to Russia, replacing 60,000 Turks evicted by the

Russians. Why did the Armenians move? Undoubtedly one of the causes was fear of

revenge. We know that the Armenians of the Ele?kirt Valley had welcomed the Russians

and given them assistance. Armenians had persecuted the Muslims of Erzurum City when

the Russians ruled and expected trouble once the Russians left. It is one thing to

mistreat Turks when the Russian Army is protecting you, quite another to stand up to

the Turks on your own.

The Russians offered free

farms and homes to Armenians who would come into their Empire. The homes and farms

of evicted Turks were empty, waiting for new dwellers. The Russians at least

promised not to tax immigrants. For poor Armenians, it was a very tempting offer.

The Armenian support for

Russian imperialism and the exchange of populations naturally caused fear and

distrust between Muslims and Armenians. It was to the benefit of the Russians to

foster that distrust.

The Russians had a very

important strategic interest in the Erzurum Vilâyeti. Erzurum, as I am sure you

know, was the keystone of Ottoman control of all of Anatolia. Impassible mountains

meant that Russian invaders had very few possible paths to Central Anatolia. Ottoman

forces in Northeastern Anatolia might have poor communications and limited supplies

and manpower, but they did have good defensive terrain, exactly the sort of terrain

that could be held by the Turkish askers, among the best defensive fighters

in the world. The Russians knew this. They knew from the bloody battles of the War

of 1877-78 that taking Eastern Anatolia would be a horrible task. They also knew

that their invasion would be aided by an internal enemy that would disrupt supplies,

hamper communications, and draw troops from the front to battle a rebellion behind

the lines. That was to be the task of the Armenians.

Unlike the Ottomans, the

Russians had good reason to want disorder in the Ottoman East. A weakened Ottoman

Empire was good for the Russians, who hoped to conquer it. Troubles in Erzurum were

also propaganda victories for the Russians. The Russians could depend on the fact

that the sufferings of the Armenians would appear in the European press. They could

count on American missionaries to send reports of real and imagined misery among the

Armenians. No reports of the equal suffering of the Muslims would be sent, nor would

they appear in European newspapers. Each report of suffering Armenians made it more

difficult for European politicians to take the side of the Ottomans.

After the war of 1877-78

the Russians made it their business to foment unrest in the eastern provinces. They

even aided Kurdish rebels against the Ottoman State. However, Russian activities had

little success with the Kurdish tribes, perhaps, as will be seen, because the

Russians were at the same time supporting the Armenian revolutionaries who were

attacking the same Kurdish tribes.

The Russians must

have been deeply involved with the activities of the Armenian revolutionaries. Until

someone studies this period in Russian archives there is little direct evidence. It

is known that the Russians promised the Armenians independence in Anatolia in World

War I, a promise they cannot have meant to keep. Circumstantial evidence for Russian collusion with the Armenian societies

is compelling. The societies held their meetings in Russian territory. Dashnak

rebels repeatedly crossed the border from the Russian border with impunity, attacked

Kurdish villages or Ottoman officials, then escaped across that same border. Russian

rifles appeared in Armenian hands all across Eastern Anatolia. Armenian terrorists

had agents within the Russian imperial armory at Tula who provided them with guns.

Can anyone believe that the Russians were such fools that they had no idea what was

happening. Did the Russian police or spies not notice that the Dashnaks were meeting

in Tiflis? Did they not notice that guns were missing?

|

| The Armenian

Societies--Dashnaks and Hunchaks |

Neither

"revolutionaries" nor "rebels" is the best word for the Armenian

terrorist groups, because it implies that the Armenian societies, the Dashnaks and

Hunchaks, wished to overthrow their own government. The Hunchaks were founded in

Switzerland by Russian Armenians. The society most involved in Erzurum, the Dashnaks, was

founded and organized in the Russian Empire. Its most active members were in Russia. Yet

the Dashnaks did not act to overthrow Russian rule in Erivan Province (today the Armenian

Republic). They directed their attention to the Ottoman Empire.

The Armenian societies espoused

the philosophies of revolutionary Europe. They were socialist, sometimes radically

socialist, and surely nationalistic. They adapted the methods of revolutionary Europe to

Anatolia. They developed cadres of supporters in Ottoman Anatolia, preparing for their

ultimate revolt, but the Hunchaks and especially the Dashnaks were in no way indigenous to

Anatolia. They were revolutionary organizations born in the soup of Russian revolution.

From the Russian Empire they spread their message to Anatolia. Ottoman gendarmes arrested

groups of Armenian rebels every year. These were usually crossing over from Russia. They

carried Russian rifles and revolutionary propaganda printed in the Russian Empire.

Like their European

counterparts, the Dashnaks and Hunchaks spent much of their energy on their own people,

spreading their doctrine, arming supporters, and preparing for ultimate revolution.

Closely following Marxist doctrine, they adopted violence as the necessary element of

change.

In their first phase of

activities, before World War I, Armenian revolutionaries seldom engaged in assassination

of Ottoman officials. The first ones whom the revolutionaries intended to murder were

members of Kurdish tribes. The intent of the Armenian revolutionaries was to foment

reprisals, especially reprisals from Kurds. This was set out in the now famous report of

the missionary educator, Cyrus Hamlin. He

reported a meeting with an Armenian rebel. The Armenian stated that the rebels would

attack Kurds, causing massacres of Armenians in retaliation. This, the Armenians assumed,

would bring European intervention, as it had in Bulgaria, and lead to the creation of an

independent Armenia. FO SOURCE? A naive belief, but one the Armenian revolutionary

societies put into practice.

Reports of Armenian rebel

actions were numerous: 200 revolutionaries killing 30 Kurds, wounding 11, and burning 25

houses in the village of Shato.

There were pitched battles between rebels and Kurds in H?n?s. One large group of revolutionaries even tried, unsuccessfully, to enter the

Ottoman Empire by attacking frontier outposts of the Ottoman military, through which they

were forced to pass.

On the eighth of November,

1899, a band of Armenian revolutionaries, armed with Russian rifles, crossed from Russia

near Ele?kirt and entered the largely Armenian village of Hanzar, killing a number of

Kurds. The kaymakam of Toprakkale marched on the village with a force of gendarmes. In the

ensuing battle, an estimated 15 rebels, 30 villagers, and 14 gendarmes and officials were

killed. The rebels escaped across the Russian border. It was rumored, although not

substantiated, that Kurds from the surrounding area took revenge on the Armenians of

Hanzar.

The Armenians who carried out

the raids on Kurds almost always came from Russian territory, occasionally passing through

Iran on their way to Anatolia.

The neighboring provinces

of Van, Bitlis, and Haleb experienced the same level of violence from the Armenian rebels.

The modus operandi of the rebels was the same. Kurds were attacked in the hope of

retaliation, which sometimes came. In some cases the rebels were killed or apprehended,

but it was usually villagers--Muslim and Armenian, innocent and guilty alike--who suffered

most.

|

Armenians Targeted for Murder

|

The other group targeted for murder by the

Armenian revolutionaries were Armenians themselves. The revolutionaries knew that

elements of the Armenian Community were supporters of the Government. Merchants,

many Community officials, and government officials (including Armenian policemen)

depended on good relations with the state for their own advancement. Even ordinary

members of the Armenian populace should have been willing to come forward with

information on the rebels, if only for a monetary reward. One of the purposes of the

Dashnak revolutionaries was to silence such men. The weapons were intimidation and

murder.

The police could not

protect Armenian informers or businessmen who took the Ottoman side. "For the

informers would have in the first place to fear the vengeance of the

revolutionaries, against which the unpaid and inefficient police force are

themselves powerless to protect them."

Records abound of

Attacks upon Armenians by Armenian revolutionaries, such as the assassination of an

Armenian who dared to serve on the government Administrative Council in Malatya.

Radical nationalists who demanded independence murdered less radical Armenians who

wished reform within the Ottoman Empire. Even the Armenian Patriarch in Istanbul was

the subject of an assassination attempt by another Armenian.

The methods of the

rebels are illustrated in a letter from the British consul Cumberbatch in Erzurum:

Sir,

I have the honor to report that the emissaries of the

revolutionary or 'Hunchakist' party are credited with the murder on the 5th

instant of two Armenians of some position in this town, named Artin Effendi

Serkissian, a lawyer, and Simon Agha Bosoyan, a merchant. They were stabbed in a

most daring manner in a crowded thoroughfare and both died instantly afterwards. One

man, a Russian Armenian of this place, has been arrested on suspicion.

It is generally thought that Artin Effendi was killed because

he was suspected of having acted as an 'informer' and because he had quite recently

refused to join the secret committee being formed here. It was not intended to

injure Simon Agha but he must have got mortally wounded in defending his friend.

At Erzinghan, some ten days ago, another Armenian called

Garabet Der Garabet was also murdered. He was considered a spy of Zekki Pasha and

the same agency is credited with his death.

In addition to forbidding any Armenian to retain any post of

Administrative employ, these even try to extort money from the richer Armenians, one

man having, three days ago, been summoned to hand over three hundred pounds to their

funds.

Even an Armenian youth of twenty, the only Christian student

at the 'Idadieh' College here has, this week, had an anonymous letter put into his

hand when he was standing alone at the door of the establishment, threatening him

with death from the same hands which had recently killed Artin Effendi if he did not

leave the school at once.

These cases will suffice to show the audacity and

determination of the dangerous faction the authorities have now to deal with.

The one activity

that most indicated the future plans of the Armenian revolutionaries was the arming

of their supporters in Eastern Anatolia. The Russian Armenians began to smuggle arms

into Erzurum and other Ottoman provinces almost immediately after the Russo-Turkish

War of 1877-78. In some areas they had occupied during the war, especially in

Beyazit, the Russians had armed the Armenians before they left. By 1880 bands of Armenians were crossing the border, leaving behind

weapons when they returned to Russian territory. It was common knowledge that this

transportation of weapons was taking place.

|

| |

One example was the

distribution of Russian Berdan military rifles in I?d?r, across the Russian border. The

rifles were distributed to Ottoman subjects who produced papers proving they were

Armenians. The guns were then smuggled into Erzurum by the purchasers. This was a public

sale. The Russian police did nothing to

interfere. Erzurum was alive with rumors,

and often exaggerations, that the Armenians were arming themselves. It is certain,

however, that the rural Armenians, as well as many in the city, were armed with Russian

weapons. As mentioned above, the Armenian revolutionaries captured by Ottoman forces were

usually armed with Russian rifles. Armenian revolutionaries were even captured in Erzurum,

itself, with rifles. The rifles had been stamped with the name of the main Armenian

revolutionary party, "Dashnaktsuthiun."

Why did Armenian villages need

to be so well armed? Contemporary observers were of two definite and differing schools of

thought. Some, perhaps naive, commentators felt that the villagers were defending

themselves from Kurdish depredations. They were only being assisted by the Armenian

Revolutionary parties. Others felt that Armenians were being armed from Russia by the

Dashnaks and Hunchaks in order to prepare for revolution, activities fostered by the

Russians.

The British reported

on such instances: In one, Ottoman forces found 34 Mauser rifles and 1,000 cartridges in

"the village of Sitaouk, about ten miles distant from Erzeroum." It was alleged

the weapons were needed for defense, but all the rifles had "recently been smuggled

from the Russian frontier, and they are all without stocks, apparently for convenience of

transport and concealment." They were being hidden in one Armenian house. The

villagers, according to the British consul, had always been individually armed. This

appears to have been a cache of arms, waiting for later use, not self-defense.

The outbreak of the world

war proved that Armenian arms caches had been secreted all over Eastern Anatolia, waiting

for the moment of rebellion. Ottoman investigators found a great deal of arms hidden in

basements, churches, and on farms, but these can only have been a small proportion of what

was hidden. The proof lies in the

tens of thousands of armed Armenians who rebelled in the Ottoman East. They were armed.

In the end it made no difference

if the Armenians armed themselves out of revolutionary fervor or out of the desire for

self-defense. When World War I began the Armenians were armed and ready to rebel. They

proved willing to use their guns against the Ottoman Government and against local Muslims.

|

The Erzurum Armenians in World War I

|

Despite all the research that has been done

recently, many questions remain on the history of the Turks and Armenians of Erzurum

Province. First among these is the question of the relocation of Erzurum's

Armenians: How many were deported; how many were refugees?

It is known that

some Erzurum Armenians were deported. They were among the first to be ordered

relocated by the Ottoman Government. The Government ordered their relocation because

they were close to the Russian border and thus were a grave danger. However, the number that was actually deported is unknown. Unreliable

accounts by missionaries and Armenians in Russia gave figures such as "10,000", a

suspiciously round and unreliable number. The deportees were mainly Armenians from

the largest cities--Erzurum, Erzincan, and Bayburt. Many of those who were in fact

deported died in Dersim. (It is worth noting that many Ottoman soldiers also died in

Dersim. While retreating from advancing Russian armies they were attacked by the

same Kurdish tribes and bandits who killed Armenians. The Dersim bandits did not

only kill Armenians. They killed anyone whom they could rob.) The actual number must

have been far fewer than 10,000.

The detailed

analysis of Ottoman records made by Professor Halaçoglu has yielded few records of those deported from Erzurum, even though very

detailed figures were kept of deportees from neighboring provinces such as Sivas and

Mamuretülaziz.

One thing is sure:

Armenian statements that almost all of the Erzurum Armenians were deported and

killed are ridiculous. This is demonstrated by the fact that so many Armenians lived

in Erzurum during the Russian occupation. When the Russians departed there were

enough Armenians remaining in Erzurum or returning from Russian Armenia to create an

army and attempt to run a government. If all the Erzurum Armenians were dead, where

did those Armenians come from? It is absurd to think, and no one then or now has

asserted, that these were Russian Armenians who had first come to Anatolia in 1916.

Some Armenians must have

remained in the villages, some ostensibly converting to Islam, some not. Most fled

to Russia, then returned when the Russians invaded Erzurum. It was the Armenians who

remained and those who returned that formed the Armenian population of Erzurum

Vilâyeti in 1918. Along with Armenian soldiers from Erivan, it was these Armenians

who slaughtered the Muslims of Erzurum in 1918.

The

strongest evidence for the survival of the Erzurum Armenians is demographic. The

1897 Russian Census recorded 1,161,909 Armenians in the Caucasus Region, an area

that included Azerbaijan, Erivan, Georgia, Kars-Ardahan, and nearby regions. This population

would have increased naturally to 1,444,000 by 1914. The Armenian population could not have increased during wartime; the men

were gone, so the native Armenian population in the Caucasus in 1917 can be assumed

to have been the same 1,444,000. Richard Hovannisian has quoted figures from

"an official Russian source" for the Armenian population of the Caucasus

in 1917: 1,783,000. Subtracting the 1,444,000 natives from the 1,783,000 leaves 339,000. Those

339,000 came from somewhere.

|

| |

The

"extra" Armenians can only have been refugees from the Ottoman Empire. In

the 339,000 would have been some refugees from Iran, and a small number of Armenians

who returned from the United States and elsewhere to fight on the Russian side, but

these small numbers would have had little effect. Hovannisian estimates: "By

the end of 1916, nearly three hundred thousand Ottoman Armenians had sought safety

in Transcaucasia, where nearly half were destined to die from famine and

disease."

Armenians in the

Russian Caucasus, 1917

|

Total Population

|

1,783,000

|

|

Native Population

|

1,443,000

|

|

Difference (Refugees)

|

339,000

|

Armenians in

Ottoman Anatolia, 1912*

|

Erzurum

|

163,000

|

|

Van

|

131,000

|

|

Bitlis

|

191,000

|

|

Total

|

485,000

|

The refugees from

Ottoman Anatolia can only have come from three provinces--Erzurum, Van, and Bitlis,

which together held 485,000 Armenians. It is unthinkable that many might have

successfully have made the journey from farther afield. If Hovannisian's figures for

1917 are correct, then 70 per cent of the Armenians from Erzurum, Van, and Bitlis

must have fled to the Russian Empire. Of course, his figures for 1917 are probably

overestimates of the Armenian population. However, if half the refugees had died,

lower estimates of the 1917 population would still have yielded a figure near

339,000.

It should also be

noted that Ottoman officials recorded that "those in towns and villages east of

the Hopa-Erzurum-H?n?s-Van line did not comply with the call to enlist but have

proceeded East to the border to join the [military] organisation in Russia." Given the number of Armenian refugees in Russia,

these deserters cannot have left their families behind.

The conclusion can

only be that most of the Armenians of Erzurum were not killed by the Turks and other

Muslims, unless they were killed in battle as they fought Ottoman forces. Nor were

many Erzurum Armenians deported. They went to the Russian Empire, where they did die

of starvation and disease in great numbers. In other words, they died just as Muslim

refugees died. They were the victims of war, just as the Muslims of Anatolia, who

also died of starvation and disease, were the victims of war.

|

| Erzurum's Muslims

During and After World War I |

Finally, what the Armenians

did to Erzurum's Muslims. I will not say much on this. You know the sad history of your

ancestors.

At the beginning of the

World War, it seemed as if Erzurum's Muslims might escape the fate of their neighbors who

were killed in Van and Bitlis. In those provinces a large proportion of the Muslim

population had been slaughtered by Armenians, both local and from Russia. However, with

the exception of Beyazit Sanca[k] in the east of the province, Erzurum was firmly under

the control of the Ottoman Army until it was quickly occupied by the Russians in 1916. The

strong Ottoman military presence undoubtedly protected the province's

Muslims from the Armenian bands that were killing Muslims elsewhere.

At least 300,000

Muslims fled Erzurum when the Russians advanced in 1916. However, even the Muslims who

remained behind were far less likely to be killed than those of Van or Bitlis. Most of the

mortality of Erzurum's Muslims does not seem to have been at the hands of the Russians.

The Russians actually seem to have been more solicitous of the welfare of the Muslims of

Erzurum during World War I than they had been in earlier wars. This does not mean that

Turks did not suffer massacre during 1916 and 1917. These massacres seem to have been

almost entirely at the hands of Armenian bands. It is doubtful if the Russians had control

over them. They had made a devil's bargain with the Armenians. In return for spying,

destroying communications and activities that hindered the Ottoman army, the Russians

tolerated the actions of Armenians.

|

|

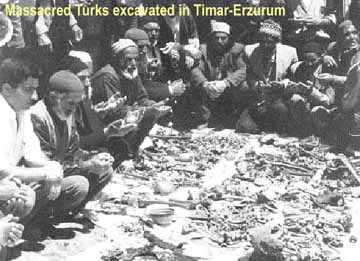

Massacred

Turks excavated in Erzurum |

Judging

by their history in Erivan, the Russians probably felt they could contain the Armenians

after the war.

The Russians were always

practical. Their soldiers raped and plundered, killing the Muslims who stood in their way,

but their leaders were practical men. They showed no special hatred of Turks or other

Muslims. Instead they acted out of self-interest. Their history shows this: In 1829 and

1878 they welcomed Armenians into the Russian Empire, giving them the Turks' homes and

farms and forgiving taxes. Why? They did it to insure a loyal population on their border.

They knew that the Armenians would be their allies against the Turks. It was a practical

decision.

The Russians had evicted Crimean

Tatars, Abhazians, Circassians, and Laz for strategic reasons or because they wanted their

territories for themselves. They replaced the evicted Muslims with Russians, other Slavs,

and Georgians. Once again, a practical, although evil, decision.

The Russians did not attempt to

exterminate the Muslims from regions where extermination would be very difficult or where

they felt they could control the populace. In conquering Daghestan and Azerbaijan they

were cruel. They slaughtered the women and children and burned the villages of the Muslims

who opposed them. But the Russians did not evict the Muslim populations. They ruled them,

but they did not destroy them.

|

One Example of an

Internal Ottoman Report:

"Many massacres were committed by the Armenians until our army

arrived in Erzurum... (after General Odesilitze left) 2,127 Muslim bodies were buried

in Erzurum's center. These are entirely men. There are ax, bayonet and bullet wounds

on the dead bodies. Lungs of the bodies were removed and sharp stakes were struck in

the eyes. There are other bodies around the city."

Official telegram of the Third Royal Army Command, addressed to the

Supreme Command, March 19, 1918; ATASE Archive of General Staff, Archive No: 4-36-71.

D. 231. G.2. K. 2820. Dos.A-69, Fih.3.

|

One can theorize that the

same principle applied in Northeastern Anatolia. The Russians expected to win World

War I. In 1856 and 1878, the Russians had been forced to relinquish Erzurum by the

British, the Germans, and the French. They knew that this time they would be allowed

to keep it. They felt the Germans would be defeated, and the British and French were

their allies. Indeed, the British promised the region to the Russians in the

Sykes-Picot Agreement.

The Russians knew that

they could not evict the entire Muslim population of Erzurum and the rest of the

Ottoman East, unless they wanted to rule over a lifeless desert. They also knew that

the region would never attract large numbers of Russian immigrants. The Russian

people would not travel to the harsh climate and dangers of the Ottoman East. If the

Russians wanted a Christian population in Eastern Anatolia, they would have to rely

on the Armenians. It is doubtful if they wished to do so. No, the Russians wanted

both Muslims and Armenians in Erzurum. They could more easily control two groups

that hated each other than they could control only one group that hated the

Russians.

It should also be added

that there were never enough Armenians in Erzurum Province to create an economically

viable land. Before the war, the Armenians had been only 17% of the population of

Erzurum Province. The Russians knew they needed the Muslim farmers and merchants of

Erzurum. The Armenians never made such rational calculations.

The worst suffering of

Erzurum's Muslims only came once the Russians had left. During the Russian

Revolution the Russian soldiers simply left Anatolia and walked home. They left

behind a small group of officers and a large number of Armenian soldiers. The

Armenians wished to make Erzurum a part of the Greater Armenian they had always

dreamed of. They could not do so if Erzurum was more than three-fourths Muslim. They

therefore began a policy of murder and forced migration of the Muslims of Erzurum,

just as they were doing to the Azeri Turks in Erivan.

The Ottoman Army

stepped in to retake Erzurum and to stop the slaughter of the Turks. The Armenians

could not stand against them. They retreated, and in their retreat killed all the

Muslims they could find. You surely know the details: In Beyazit Sanca[k], half the villages were destroyed, half the population

of Beyazit City dead. In the cities of Erzincan, Bayburt, and Tercan, all the Muslims who could

not escape to the mountains were killed. Each of those cities was destroyed. All the villages in the path of the retreating Armenians were likewise ruined,

their people killed. Ottoman soldiers retaking the cities found hideous

sites--streets littered with thousands of bodies, wells filled with corpses. The

city of Erzurum itself was described by the Ottoman captain who entered it, Ahmet

Refik, as a "city of ruins." In the first week after capturing the city,

Ottoman burial details counted more than 2,000 bodies, and many had not yet been

included. Ottoman forces overtook the Armenians so quickly that the majority of the

inhabitants of Erzurum were saved. Nevertheless, 20% of the Muslims of Erzurum City

had been killed.

An Austrian journalist on

the scene reported:

All the villages from Trabzon to Erzincan and from

Erzincan to Erzurum are destroyed. Corpses of Turks brutally and cruelly slain are

everywhere. I am now in Erzurum, and what I see is terrible. Almost the whole city

is destroyed. The smell of corpses still fills the air.

The Armenians were

retreating before the Ottoman Army. They were in danger. Yet they stopped whenever

they could to kill the innocent Muslims of Erzurum, despite the risk to their own

safety. This kind of hatred and madness cannot be explained. It is often falsely

claimed that the Turks committed a genocide of the Armenians. Yet this was the real

genocide, a genocide of the Turks.

At the end of the war,

one-third of the Muslims of Erzurum Province were dead.

|

| Conclusion |

Much can be learned from the

history of Erzurum. Armenians were a part of the Ottoman Empire, like the other subjects

of the sultan. They had problems. They had complaints. So did the other Ottoman subjects.

But were the Armenians persecuted? No. In fact, in many ways the Armenians of Ottoman

Erzurum had a better life than the Muslims.

Did the Ottomans select the

Armenians for ill-treatment? No. The Ottomans wanted Erzurum to be quiet, peaceful, and

productive. The Ottomans did not always succeed. In the world in which they lived, with so

many powerful enemies and so little money, the Ottomans could not insure a peaceful and

productive Erzurum, but they tried. That was only rational; a peaceful and prosperous

Erzurum meant a better Ottoman Empire. And the Ottomans were rational men who knew what

was good for their Empire.

Why, then, did Erzurum become

such a disaster in the time of World War I? To find the guilty parties, one must look to

the Armenian Nationalists and the Russians.

Like the Ottomans, the Russians

were rational. The Tsar wanted to expand his Empire. To do so, he had to disrupt the

Ottoman Empire. The Russians did not care about the fate of the Muslims of Erzurum. They

only cared about their own plans. They therefore supported the Armenian rebels. They

supported the Armenians because the Armenians would give the Russians what they wanted--a

weakened Ottoman Empire that would more easily defeated. The Russian policy was cold,

calculating, and immoral, but rational.

The policy of the Armenian

Nationalists was not rational, and thus it was much more dangerous for the Muslims of

Erzurum.

The Armenians were people who

had lived among the Turks for 800 years. They were a minority that lived alongside a very

powerful majority. The majority, the Muslims, could have squashed the Armenians at any

time. They did not do so. Instead, they allowed the Armenians to keep their religion and

their customs. They even allowed the Armenians to become richer than the Muslims and to

have better schools. They allowed foreigners to feed only the Armenians in time of

starvation, but not the Muslims, and to provide a good education to the Armenians, but not

the Muslims. The Ottomans took the Armenians into the political process in which Armenians

became policemen, officials, and even ministers of state and members of parliament. Yet

the Armenian minority rebelled and ultimately lost everything. This was madness the

madness of nationalism.

The Armenian nationalists

declared that they had special rights not only the right to vote, not only the right

to become an important part of the Government, not only the right to become educated and

even wealthy. No, they demanded the counterfeit right of their 17% to rule over the other

83% of the people of Erzurum. They demanded the right to deny religious and cultural

freedom to the Turks who had allowed those freedoms to the Armenians. Ultimately, they

demanded the right to force out the Muslim majority and to make Erzurum into Armenia.

These were not rights. They were

crimes. As crimes often do, they led to the destruction of the criminals. They also led to

the deaths of hundreds of thousands of innocent Muslims and Armenians.

It was not the failings of the

Ottoman Government that destroyed Ottoman Erzurum. It was not war alone that destroyed

Ottoman Erzurum. It was the crimes of the Armenian Nationalists and their friends, the

Russian imperialists that destroyed Erzurum.

Justin McCarthy

|

|

From atmg.org

|

| Reflections

from Holdwater |

It is now late May 2003, and I'm putting the finishing touches on

TAT... I ran into this article, and decided to incorporate it as a "last minute"

addition. Like all of Justin McCarthy's wonderful works, I found "The Destruction of

Ottoman Erzurum by Armenians" very illuminating. For example, although I was aware

the Kurds (whom the Turks would refer to as "mountain Turks" to squash their

sense of identity) were a bit on the uncontrollable side, during this period of history, I

thought they would firmly be on the side of the Turks, since the Armenians were making

mincemeat out of all Moslems. However, it seems the Kurds were attacking the Turks like

they were attacking the Armenians. (They didn't discriminate! They believed in equal

opportunity...)

The article really gave me a much better idea as to the basis of

why the Armenians behaved in the way they did, and I can only assume the developments in

the other vilayets where the Armenians wreaked havoc were not far off from what we have

learned took place in Erzurum. I was also fascinated by the behavior of the Russians.... I

thought they might have lent a considerable hand with the slaughter of the Moslems,

keeping in mind their record for Turkish ethnic cleansing that I first learned in scope

when I read Dr. McCarthy's "Death and Exile: The Ethnic Cleansing of Ottoman

Muslims, 1821-1922"... but it seems the Russians' plans were a little more devious this time around, and they probably

maintained a hands-off policy as far as the atrocities, allowing the Armenians to do the

dirty work. This is in keeping with the observations

of Russian soldiers who were appalled at

the inhumanity on display from the Armenians.

As this is a later paper based on Dr. McCarthy's work (as opposed

to the other works of his that I've read and are featured on TAT), I can't help noticing

his generally clinical air has started showing signs of mild outrage. The more he has

applied himself to this topic as a serious scholar, the more he has come to the conclusion

the Armenian "Genocide" is just a bunch of Frank Pallone. (That's a

congressional synonym for the rhyme word, "baloney.") Listen:

The Armenians were retreating before the Ottoman Army. They

were in danger. Yet they stopped whenever they could to kill the innocent Muslims of

Erzurum, despite the risk to their own safety. This kind of hatred and madness cannot be

explained. It is often falsely claimed that the Turks committed a genocide of the

Armenians. Yet this was the real genocide, a genocide of the Turks.

The Justin McCarthy I'm familiar with would have left out the

word "falsely" in the next-to-last-sentence, as Prof. McCarthy has operated from

the standpoint, "Yes, the evidence is overwhelming that there was no

government-supported extermination policy, but there is still room for doubt." That's

because the professor is a true scholar, and the only force that guides him is the truth.

If conclusive evidence were to arrive the genocide actually took place, Prof. McCarthy

would be the first to acknowledge the genocide. I would be among those to acknowledge it

soon afterwards.... because truth is the only thing that matters.

With the passing years, Prof. McCarthy is now telling us flat out

there was no Armenian "Genocide." I understand

completely. Constructing this web site has increased my knowledge on the topic manifold,

and as much as I maintained an open mind (and still do)... the more I discovered new

arguments from both sides, the more I became convinced... as Sam Weems said, in so many

words... that the Armenian "Genocide" is about as credible as a three dollar

bill.

-------------------

Related: An Ottoman report on

atrocities in Erzurum

|

|