|

|

TURKEY AND THE JEWS OF EUROPE DURING WORLD WAR

II

By Stanford J. Shaw

|

|

|

| |

"While six million Jews were being exterminated by the Nazis, the rescue of some

15,000 Turkish Jews from France, and even of some 100,000 Jews from Eastern Europe might

well be considered as relatively insignificant in comparison. It was, however, very

significant to the people who were rescued, and above all it showed that, as had been the

case for more than five centuries, Turks and Jews continued to help each other in times of

great crises."

STANFORD J. SHAW

Professor of Turkish History

Bilkent University, Ankara, Turkey

The French and foreign Jews interned in the camp formed two hostile groups:

the French Jews affirmed that their being there was the fault of the foreigners, and they

hoped for a special treatment by the authorities which never came....The French Jews

believed that they would be freed soon, and so they did not want to be seen in solidarity

with the foreigners.... The French Jew believed that it was because of the former that he

was in the camp. He spoke of the foreign Jew with disdain.... Their deception brought even

more bitterness when they saw that the Germans made no distinction between Jews and

Jews.... The foreign Jews in turn reproached the French Jews for the attitude of France.

This led to interminable discussions that ended in tumult and dispute....When Turkish Jews

not yet in the camps were ordered to join other foreign Jews in forced labor gangs, the

Turkish consulate advised them not to report, and sent protests to the French government,

which usually led to the Turkish Jews being exempted. To quote a report from Turkish

Ambassador Behiç Erkin (Vichy) to Ankara on 15 Decmber 1942:

|

|

Behic Erkin, from WWI days |

I have wired the French Foreign Ministry by telegram asking that

Turkish Jewish subjects not be included in the decision recently published in the

newspapers by the Prefecture of Marseilles that all foreign Jews who entered France since

December 1933 and who are without work or in need be gathered in foreign worker groups....

At the same time, Erkin sent the following instructions to the Turkish Consul-General in

Marseilles, Bedi'i Arbel:

Jewish citizens whose

papers are in order cannot be subjected to forced labor, and if such situations arise, it

is natural that we should provide them with protection. The prefects of police should be

reminded of the relevant instructions, and it is necessary to intervene with the competent

authorities when necessary.

|

|

Turkish diplomats in France also spent a good deal of time organizing 'train

caravans' to take Turkish Jews back to Turkey. This actually was encouraged by the

Vichy government was well as the French authorities in German-occupied France as the

only way to make sure that Turkish Jews were not subjected to the anti Jewish laws

applied to French Jews, because the Nazi occupation officials themselves were

increasingly unhappy about the exemptions and were regularly demanding that they be

brought to an end. Thus the French Foreign Ministry wrote to the Turkish Embassy at

Vichy on 13 January 1943, after the French finally had accepted the Turkish argument

that it was illegal for them to discriminate among Turkish citizens of different

religions:

To avoid the application of these measures to Turkish citizens, the Ministry of

Foreign Affairs would be disposed to look favorably on the return of the interested

parties to their countries of origin.

In the middle of 1943, the Nazi occupying authorities, inspired by Adolph Eichmann,

finally issued an ultimatum to Turkey and other neutral countries that they would

have to repatriate all their Jewish citizens in France, after which all those who

remained would be treated the same as French Jews.

|

| |

|

|

Numan

Menemencioglu |

Most of the neutral countries agreed to this right away and

evacuated their Jews quickly because they were able to send them home directly without

having to send them through third countries. Turkey was unable to do the same because with

the Mediterranean closed to shipping, the only way to send Turkish Jews back was by train

through Southeastern Europe. The Nazis issued group visas for the Jews being evacuated,

but the various countries located along the path of the trains were not at all anxious to

help Jews escape extermination. The most notorious of these were Croatia, Serbia and

Bulgaria, which caused many difficulties to prevent the trains from passing through their

territory on their way to Turkey. Finally, however, the Turkish diplomats were able to

organize some four train caravans during 1943 and eight more in 1944, which together

transported some 2,000 Jews to Istanbul. Other Jews were helped to flee to the areas of

southern France under Italian occupation, where they were treated much better unti

Mussolini fell and Italy was occupied by the Germans in the middle of 1943. They also fled

across the Pyranees into Franco's Spain, where they were given refugee despite Spain's

alliance with Germany, or across the Mediterranean to North Africa. There they were

interned but not persecuted, except in Algeria, where the French colons were even more

anti-Semitic than were the Germans. In 1944, when the Vichy government was thinking of

deporting all 10,000 Turkish Jews living in its territory to the East for extermination,

Turkish Foreign Minister Numan Menemencioglu intervened with the French government, on the

direct orders of President Ismet Inönü, stating that such an act would be considered

unfriendly by Turkey and would cause a major diplomatic incident, including perhaps a

complete break in diplomatic relations. This convinced Vichy to abandon the plan and saved

these Jews from almost certain death. The original correspondence on this matter has not

yet been uncovered. Turkey's key roll in this matter is, however, well documented in other

sources. The American Ambassador at Ankara, Laurence Steinhardt, himself a Jew, wrote the

head of the Jewish Agency office in Istanbul, Chaim (Charles) Barlas on 9 February 1944:

... It has been a great satisfaction to me personally to have been in a position to

have intervened with at least some degree of success on behalf of former Turkish citizens

in France of Jewish origin. As I explained to you yesterday, while the Vichy government

has as yet given no commitment to the Turkish Government, there is every evidence that the

intervention of the Turkish authorities has caused the Vichy authorities to at least

postpone if [not] altogether abandon their apparent intention to exile these unfortunates

to almost certain death by turning them over to the Nazi authorities.

|

|

This is confirmed in the memoirs of Steinhart's German

counterpart in Ankara, Ambassador Franz von Papen, who, of course, emphasized his

own role in the affair:

|

|

Franz

von Papen |

I learned through one of the German émigré

professors that the Secretary of the Jewish Agency had asked me to intervene in the

matter of the threatened deportation to camps in Poland of 10,000 Jews living in

Southern France. Most of them were former Turkish citizens of Levantine origin. I

promised my help and discussed the matter with m. Menemencioglu. There was no legal

basis to warrant any official action on his part, but he authorized me to inform

Hitler that the deportation of these former Turkish citizens would cause a sensation

in Turkey and endanger friendly relations between the two countries. This demarche

succeeded in quashing the whole affair.

Finally, one of Barlas's associates at the Jewish Agency office in Istanbul, Dr.

Chaim Pazner, stated to the Second Yad Vashem International Historical Conference on

Rescue Attempts during the Holocaust, held in Jerusalem in April 1974:

In December 1943, Chaim Barlas notified me from Istanbul that he had received a

cable from Isaac Wiesmann, representative of the World Jewish Congress in Lisbon,

that approximately ten thousand Jews who were Turkish citizens, but had been living

in France for years and had neglected to register and renew their Turkish

citizenship with the Turkish representation in France, were in danger of being

deported to the death camps. Weismann requested that Barlas contact the competent

Turkish authorities and attempt to save the above-mentioned Jews. Upon receiving the

telegram, Barlas immediately turned to the Turkish Foreign Ministry in Ankara,

submitted a detailed memorandum on the subject, and requested urgent action by the

Turkish legation in Paris.... We later received word from Istanbul and Paris that,

with the exception of several score, these ten thousand Jews were saved from

extinction.

|

| |

In addition to providing material assistance to Turkish jews persecuted in France

and other countries occupied by the Nazis in Western Europe, Turkey also helped East

European Jews persecuted in countries such as Greece, Lithuania, Rumania, Hungary,

Yugoslavia and Bulgaria. Right from the start of the war, the Turkish government

permitted the Jewish Agency to maintain a rescue office at the Pera Palas and other

hotels in the Tepebasi section of Istanbul, overlooking the Golden Horn, under the

direction of Chaim (Charles) Barlas, as we have seen. In addition, other Jewish

organizations based in Palestine were allowed to maintain representative offices in

Istanbul. Many were sent by kibbutzim wanting to rescue members from persecution or

death in Eastern Europe. First, however, they had to learn what was going on in

those countries. Fore this purpose they sent their agents from Istanbul to these

countries to gather information. They used the Turkish post office to send letters

to Jews in these countries and to receive responses. They sent packages of clothing

and food to help out when needed. In all of these activities, the Turkish Ministry

of Finance, despite Turkey's severe financial problems resulting from the war,

provided them with the hard currency needed to meet their expenses, and the Turkish

diplomats stationed in these countries allowed their facilities to be used when

needed.

With this help, the Jewish rescue groups based in Istanbul were able to organize

trains and steamships which carried to safety in Turkey and beyond as many refugees

that could leave their homes. In this they were vigorously opposed, not only by the

Nazis, but also by the British government, which correctly feared that most of the

refugees arriving in Turkey would go on in Palestine. Turkey as a matter of fact

made this a condition of its agreement to allow these refugees to enter its

territory. It would not support large number of immigrants of this sort since people

in Turkey were already starving as a result of wartime shortages and blockades in

the Mediterranean. It did allow the Jewish Agency and other organizations to bring

these refugees through Turkey on their way to Palestine, however, permitting the

Mossad organization to send them in small boats across the Mediterranean from

southern Turkey. When the British were successful in preventing some of these

refugees from going to Palestine, instead interring them on Cyprus, the Turkish

government allowed them to remain in Turkey far beyond the limits of their transit

visas, in many cases right until the end of the war.

|

| |

|

|

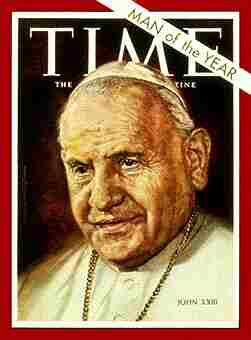

Pope John

XXII |

The Vatican's reluctance to help the persecuted Jews of Europe is

well documented. This was not the case, however, with the Papal Nuncio in Istanbul from

1935 until 1944, Archbishop Angelo Roncalli, who later became Pope John XXIII. Roncalli

was a very unusual person. When he first came to Turkey even before the war, he taught his

parishioners, including many Greeks and Armenians, that they should forget their

prejudices against Turks and Muslims, that they should follow the precepts of Christian

charity and love in dealing with them, that they should forget the bigotries of the past

and work together with their fellow Turkish citizens to build a new and modern Republic.

Roncalli learned Turkish himself and recited the Christmas mass in Turkish at least one in

Istanbul. This greatly pleased the Turkish people, who had become increasingly disgusted

with the insistence of Christians in Turkey to continue using Greek, Italian, French or

Armenian in preference to Turkish, unlike the Jews who had emphasized the use of Turkish

instead of French and Ladino since the mid 1930's. During the war Roncalli went much

further. He got the Sisters of Sion order of nuns to use their own communications network

in Eastern Europe to help the Jewish Agency pass communications, clothing and food to Jews

in Hungary in particular. Other Vatican couriers going from Istanbul to Eastern Europe did

the same thing as the result of Roncalli's orders. He even got them to carry false

Certificates of Conversion to Hungarian Jews to help save them from the Nazis. A

remarkable person indeed, early in the year 2000 was recognized as a Saint by the Catholic

Church.

|

|

Turkey also acted to help the Jews of Greece during the Holocaust. Just as was the

case in the areas of southern France occupied by Italy, so also in Greece, during

the time it was under Italian occupation early in the war, Greek Jews did reasonably

well, despite pressure from Greeks themselves, whose long tradition of anti-Semitism

led them to hope that the foreign occupation would at least enable them to get rid

of their Jewish fellow-citizens. Even after German troops entered Greece to help the

Italians against Greek guerilla resistance. The Italian troops protected Greek Jews

from persecution at the hands of the Germans and the Greeks. Once Italy fell out of

the war in 1943 and the Germans took over, however, the situation of Jews in Greece

became worse than anywhere else in Europe, since while many Frenchmen and Dutchmen,

and even Germans had helped the Jews to escape the Nazi persecution, most Greeks did

none of this due to their long history of pervasive anti-Semitism. The only Greeks

who helped Jews were the partisans fighting against the Nazis, who did help Jewish

groups spiriting Jews out of Greece, either across the Aegean and Eastern

Mediterranean to Turkey or Palestine, or by land across the Maritza river into

Turkey. Most Greek Jews were in fact exterminated by the Nazis. Jewish synagogues

and schools were systematically destroyed. Even the great Jewish cemetery at

Salonica was wiped out. After the war, instead of restoring it, Greece built the new

Aristotle University of Salonica on the cemetery lands.. The Turkish consuls in

Greece, at Athens, Salonica and Gümülcine as well as on the islands of Midilli and

Rhodes provided the same sort of assistance that the Turkish consuls did in France,

also organizing boats to carry Jews to safety in Turkey and intervening with the

Germans to exempt Turkish Jews from persecution and extermination. The most

outstanding example of this came with the activities of Consul Selahattin Ülkümen

in Rhodes, who got the Nazis to spare the Turkish Jews on the island, andwho as a

result was subsequently imprisoned by the Nazis after his consulate was bombed and

his pregnant wife killed by the Germans. The Turkish guards on the Greek-Turkish

border allowed Jews coming from Greece as well as Bulgaria to enter turkey even

though most of them had no papers at all. Camps were set up for them near Edirne,

and ultimately they were allowed to pass on to Istanbul, and, for most of them, to

join the other refugees doing by small boats from the Mediterranean coast of

southern Turkey to Palestine. Turkey thus provided major assistance to Jews being

persecuted by the Nazis, despite pressure from the British, who wanted to stop

Jewish immigration to Palestine, and by the Nazis, who demanded not only that this

rescue work be stopped, but also that all Turkish Jews, as well as the refugees, be

sent to Germany for extermination. Turkey steadfastly refused these demands and

continued to assist European Jewry to escape from the Holocaust and in most cases go

to Palestine. . Only after it was assured of an Allied victory, and the

impossibility of a German invasion, by late 1943, was it ready to enter the war.

Even then, however, it reacted to appeals for delay from the Jewish Agency, which

understood that immediate Turkish entry would cut off the escape routes through

Turkey which were enabling thousand of Jews to escape the Nazis throughout Europe,

postponing its entry for almost a year. While six million Jews were being

exterminated by the Nazis, the rescue of some 15,000 Turkish Jews from France, and

even of some 100,000 Jews from Eastern Europe might well be considered as relatively

insignificant in comparison. It was, however, very significant to the people who

were rescued, and above all it showed that, as had been the case for more than five

centuries, Turks and Jews continued to help each other in times of great crises.

Stanford J. Shaw is Professor Emeritus of Turkish History, University of

California Los Angeles Professor of Turkish History, Bilkent University, Ankara,

Turkey

|

| |

Bibliography :

Stanford J. Shaw, Turkey and the Holocaust: Turkey's Role in Rescuing Turkish and

European Jewry from Nazi Persecution, 1933-1945.

Stanford J. Shaw, The Jews of the Ottoman Empire and the Turkish Republic. Both

books were published both by the New York University Press and by MacMillan publishers in

England (now called Palgrave Publishers). Unfortunately the American editions, which were

in paperback, are out of print, but I understand that the British editions (only in

hardcover) are still available.

The above was taken from this site.

|

|