|

|

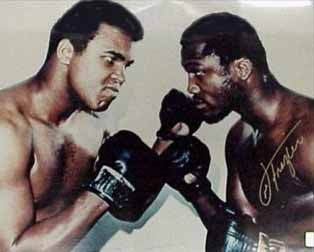

Joe Frazier used to take potshots at Muhammad Ali by using Ali's former name,

"Cassius Clay." It was a sign of disrespect, Frazier's way of

saying, "I am your foe." Similarly, Turk-haters to this day still

refer to Istanbul as "Constantinople."

|

|

"Smokin'

Joe" Frazier (right) couldn't match wits with Ali,

and his childish recourse boiled down to hitting below the

belt. Imagine that you want to be called by a certain name,

and you have to deal with those who insist on calling you

by another name.

CLICK ON PIC for sound! |

The city signified

Christendom as part of the Byzantine Empire; "Byzantium" had been

changed to "Constantinople," to honor the Eastern Roman Empire's

Constantine the Great. The Western Empire fell to "barbarians," as

we are often told in western history, as though the Romans were perfect

gentlemen. Constantinople, as a result, gained even more importance as a

symbol of Christian civilization and dominance.

Sultan Mehmed II conquered the city in 1453, and changed its name to

"Istanbul." It's not very often a conquered city retains its old

name. "New Amsterdam" became "New York," after the British

took over from the Dutch. The Dutch also couldn't hold sway when their

"Batavia" (which the Dutch had renamed from a variation of Jakarta,

circa 1619) in Indonesia finally became "Jakarta" again.

No one today calls these cities/provinces by their old names. Yet because the

idea persists in the minds of Turk-haters that Turks still don't belong in

what was once such a symbolically Christian city, the only way they can show

their contempt is by insisting the city is still "Constantinople."

This is "Christian code" for "Turks don't belong here."

That is just plain rude, especially after more than half a millennium of

ownership. Cities and countries are called by the names used by their

occupants. By what stretch of the imagination would an empire known for its

Islamic foundation retain a symbolically Christian name as

"Constantinople"? It defies common sense.

Accounts of the name change have it that the city's name was

"officially" changed in March 28, 1930. (Popularized by the 1953

song, "Istanbul not Constantinople," by The Four Lads. In

case your browser did not give a taste, here's a sample.) What does

that mean? Is there a "name change registrar" that countries apply

to?

(An online encyclopedia hijacked by tenacious pro-Armenians has a footnote for

this "fact," pointing to a [at the time, not operational] Library of

Congress link, the Federal Research Division for Country Studies. The country

is "Albania.")

(Someone in Internet-Land cited this very tainted source in response to

another who claimed the name was called "Istanbul." The message was

capped with: "I bet the Dutch and everybody else in the 17th century

told friends they were going to Constantinople, if they were going."

In other words, if Christendom called the city by its old Christian name,

thanks to spite, wishful thinking or ignorance, it shouldn't matter what the

owners of the city called their city. Mighty fine logic, there.)

I don't know exactly what transpired on March 28, 1930, where it's said

"Angora" was also "officially" changed to

"Ankara." But if the government of Ataturk made such an

announcement, it was not in terms of acknowledging the city was named

"Constantinople." What Ataturk was telling the arrogant West was,

the name of this city has been Istanbul for half a millennium, it's time to

stop behaving like "Joe Frazier," and begin to act as respectful

neighbors.

This page was mainly inspired by a viewing of the documentary, "The Ottoman War Machine."

Real Ottoman historians were on call for a change (not that the producers

always listened to them), and the program stated — as common sense should

tell all — that as soon as Constantinople was conquered, the name was

changed to Istanbul. (Take a listen to the passage,

preceded by Dr. Heath Lowry's comments.)

There are a number of speculative explanations for the origin of

"Istanbul," such as deriving from the Greek "Stanbulin"

("to the city"), and what religious devotees referred to as "Islambol"

(Much Islam). In coinage and some documents "Konstantiniye," a

derivation of the Christian name was used, perhaps as a gesture of goodwill

toward childish Europeans. (Mustafa III, the sultan during 1757-73) actually prohibited

the name 'Konstantiniye,' but old habits die hard.) The fact is,

however, the name of the city for the Turks was "Istanbul." This

common usage is what persuaded western travellers to call the city "Stamboul,"

in their writings.

From the Catholic Encyclopedia of 1908:

"Thus was granted the sacrilegious prayer of so

many Greeks, blinded by unreasoning hate, that henceforth, not the tiara, but

the turban should rule in the city of Constantine. Even the name of the

city was changed. The Turks call it officially (in Arabic) Der-es-Saadet,

Door of Happiness, or (chiefly on coins) Konstantinieh. Their usual name for

it is Stamboul, or rather Istamboul, a corruption of the Greek expression eis

ten polin (pronounced stimboli), perhaps under the influence of a form,

Islamboul, which could pass for 'the city of Islam'."

Again, note the source. Even the Catholic Encyclopedia was not insisting on

"Constantinople," back in 1908. If they are saying the name was

changed well before 1930, then what could have been the reason for the Turkish

announcement in 1930... other than to remind the world to please be

courteous, and to recognize the reality of the situation.

To seal this deal with good, old-fashiohed logic: years ago, the American (and

probably some other English-speaking worldwide) media decided to be proper and

paid respect to whomever decreed we should alter the names of certain Asian

cities and countries, conforming to what their inhabitants called them. Note

the changes weren''t drastic, like "Istanbul" from

"Constantinople." No, whomever decided to make these changes

(perhaps they applied to the same phantom office Turkey went to in 1930) was

making the changes according to the sound of what the inhabitants

called their own cities.

Thus, "Peking" became "Beijing." Now, this was a tough

one, because "Peking" was ingrained in the American mind. (Why, what

would now become of the famous dish, Peking duck?) But the years passed, and

"Beijing" took hold. It's now actually "Peking" that

sounds strange, a relic from another age.

But good intentions go only so far. When the media used the new word,

"Kampuchea" for "Cambodia," readers had no idea what the

reference was. So, editors bowed to the necessity for comprehension to take

precedence, and now we're largely back to "Cambodia" again.

Above, you read an Ottoman sultan was so fed up with the lack of respect being

paid to the name of the capital city, he forbid the usage of the Turkish

variation for "Constantinople." That was back in the mid-to-late

18th century. But the name was so ingrained in some quarters, the usage came

back with a vengeance, even appearing in coins and some Ottoman documents.

Now, you might be saying, wouldn't such usage confirm that it was the Turks

who called their city "Constantinople"? Don't be rash; come the 19th

century, the "Sick Man" was so weakened, the Ottoman sultans were

kowtowing to the powerful west at every opportunity. Thus, the humiliating

capitulations were imposed, thus Ottoman territory would be taken with nary a

protest, thus foreigners would be excluded from Ottoman law... and thus

Ottoman sovereignty would be sacrificed with the agreement for foreign consuls

to keep an eye on Christian minorities.

If the West was going to insist on "Constantinople" and there was

nothing a weak Ottoman government could do about it (the Ottomans were like

the "Rodney Dangerfield" of the world powers; they would get

"no respect," at every opportunity), then they must have figured

(like the editors deciding upon Kampuchea-Cambodia) that comprehension must

not be sacrificed. The Turks would call their city "Istanbul" as

they have for centuries, but for the benefit of "those in charge"

(truly, during these latter years, the Ottoman Empire was more like a

glorified European colony), the Turks in charge must have concluded giving

them this wouldn't be too much skin off their nose.

But when the "Sick Man" was overthrown, and modern Turkey was

established in 1923, does anyone out there think Mustafa Kemal Ataturk -- who

made a point of doing away with the subservient Ottoman attitude and in

preserving Turkish dignity -- would have, for one moment, considered calling

Istanbul by its "other name"? Certainly not. Those who insist that

Turkey made the "name change" in 1930 can now see this name was

changed long before. What happened in 1930 was not a name change. Obviously,

the West was still pulling its "Joe Frazier" act, and using

"Christian code" on cities such as Constantinople and Smyrna. What

happened in 1930 was a reminder that these names were already changed, and a

request that the arrogant West please get with the program.

Let's cover a few other sources that examine this name game.

|

|

|

| Known

as Istanbul even before 1453 conquest |

"[The city's] name, in everyday spoken Turkish, even before the conquest, was

a corruption of the Greek phrase for `into the city', eis teen teen polin: Istanbul."

CONSTANTINOPLE : City of the World's Desire

1453-1924 Philip Mansel, New York, 1996; Chapter I. Excerpts.

|

ISTANBUL: AN ISLAMIC CITY

|

The following

is from pp. 252-53, a book by the noted Turkish historian, Halil Inalcik. Note the

psychology behind the transformation of the city, after its conquest. (As the Sephardic

Studies page on the subject claims, "Recent research has shown that the

name 'Istanbul' was used if not during the Byzantine period, at least during the

11th century and that the Turks knew the city by this name." The name of

Istanbul existed for the Turks centuries before the city's conquest.) Here the

sultan is taking pains to turn churches into mosques and paying tribute to the

spirituality of the affair, and he was going to keep the Christian name,

"Constantinople"? Does that make any sense?

Seyh Aq Semseddin was also charged, upon the Sultan’s order with locating the tomb

of Ayyüb al-Ansari. Its discovery by the Seyh was no les miraculous and significant

than the conquest. It assured the Muslim that providence was still on their side.

Later, Mehmed built a mausoleum at the site, a mosque and a dervish convent.

Ayyüb’s tomb, which rapidly grew into a town outside the walls of the city on the

Golden Horn, became the most sacred place in Istanbul. Each day hundreds of

believers would visit with offerings and seek the saint’s help. The most famous of

the dervish convents as well as a huge cemetery clustered around the tomb. It is

also significant that each Sultan upon his accession to the throne visited the tomb

following the same route as the legend described for Ayyüb. At the site, the most

venerated Seyh of the day girded the Sultan with the sacred sword of ghaza. Thus,

the saint’s presence not only made the whole area of Istanbul a consecrated place

for Muslims, but also gave the Sultan rule over the Muslims a religious sanction.

It should be noted that every Ottoman city had its own wali or saint whose tomb,

usually located on a hill-top outside the city, combined Islamic mystic tradition

with a pre-Islamic mountain cult. Cities were regarded as persons and a prayer

formula recited each time the name of the city was mentioned.

Constantinople becomes ‘Islambol’

After the conquest, Mehmed’s first act was to convert Constantinople into an

Islamic city. The preamble of his waaf deed for his mosque reads: ‘Sultan Mehmed

conquered Kostantiniyye with the help of God. It was an abode of idols ... He

converted its churches of beautiful decoration into Islamic colleges and mosques.’

There were six churches converted into mosques and one into a college. Interestingly

enough, the monastery of Aya-Marma was given to Baba Haydari dervishes. In general

the best sites were assigned either to members of the military or to the men of

religion including the Süfi orders.

On the day following the conquest the Sultan went straight to St Sophia church and

converted it into a mosque, saying there his first prayers, an act that symbolized

the dedication of the city as an Islamic one. He also solemnly gave it the name ‘Islam-bol’

(Islam abounds), which actually reflects the centuries — long aspiration of

Muslims to convert the great city of Constantine (‘Qostantiyya al-Kubra) into a

city of Islam. The new name was hereafter strictly maintained by the ulema, though

the people at large continued to use the pre-Ottoman Turkish name Istanbul. Folk

memory of the congregational prayers after the conquest, as described by Evliya

Çelebi, records: ‘When the muezzins began to recite the verse inn’ Allaha wa

mala ’ikatahu’ in a touching tone, Aq-Semseddin, taking Sultan’s Mehmed by his

arm in great respect led him to the pulpit. Then be called out in a strong deep

voice, “Praise to God, Lord of all creatures,” and the ghazis present in the

mosque, deeply touched, broke into tears of joy.’

Islamic faith and the popular imagination combined to convert Constantinople into

Islambol. For the Ottomans it was a Muslim city from the time it held the sacred

remains of the Prophet’s companions. In Islamic tradition, a place where Muslims

had built a mosque and prayed was considered Islamic territory. The churches, Hagia

Sophia in particular, were admired as works of God which the Muslims believed He

would ultimately grant to the true religion. Legend tells us that Abü Ayyub al-Ansüri

performed his prayers there before his martyrdom. Also, while an area or a city of

non - Muslims who had submitted to a Muslim state was accepted as, administratively,

a part of Islamic territory, its ultimate Islamization remained a constant hope.

Tolerant enough to resettle the city with Greeks, Armenians, and Jews, Mehmed the

Conqueror nevertheless took measures to ensure that ‘Islambol’ had a Muslim

majority — a policy systematically applied to the major cities conquered for

Islam.

(With apologies that the following footnotes do not have

placements in the text above. But for those who can put two and two together...)

16 Wittek, ‘Ayvansaray ...‘ (n. 5 above), 5234. For the walkfiyya of the complex

see Fatih Mehmed Il Vakfiyeleri (Vakiflar Umum Müdürlügü, Ankara, 1938),

285-327.

17 On the ceremony of swordgirding see I. H. Uzunçarsili, Osmanli Devletinin Saray

Teski (Türk Tarih Kurumu, Ankara 1945), 189-200. On the town of Eyüp now see Eyüp:

Dün/Bugün, 11-12 Aralik 1993, Istanbul: Tarih Vakfi, 1993, 1-23.

18 On the dervish convents built on a hill outside the Ottoman towns see Semavi

Eyice, ‘Zaviyeler ve Zaviyeli Camiler’, Istanbul Universitesi liktisat

Fakültesi Mecmuasi, xxiii (1962-3), 23, 29; F. Hasluck, Christianity and Islam

under the Sultans (ed. Margaret M. Hasluck Oxford, 1929), i, 324-5; 0. E. von

Grunebaum, ‘The Sacred Character of Islamic Cities’, A. Badawi, ed., Mcüanges

Taha Husajn (1962) 25-37.

19 Conqueror’s waqfiyya in Evliya Çelebi, Seyahatname, (see n. 11), 30-31.

20 Mentioned in the Ottoman survey of Istanbul made in 1455. The survey, preserved

at 21 the Topkapi Palace Archives, Istanbul, is being prepared for publication. See

H. Inalcik, ‘Istanbul’, El iv, 224,

22 Evliya Çelebi, Seyahatname, 111.

23 The Qur’an, 2: 30-34.

24 Evliya Çelebi, Seyahatname, i, 76.

25 H. Inalcik, ‘Istanbul’, (n. 21), 238. H. Inalcik, ‘Ottoman Methods of

Conquest’, Studia Islamica, 11, (1954), 122-9. For the Balkans see Structure

sociale et developpement culturel des villes sud-est europeennes et adriatiques

(Bucharest, 1975); N. Todorov, La ville balkanique aux XV-XIX siecles, developpement

socioeconomique et demographique

(Thanks to Sukru Aya.)

|

| "CONSTANTINOPLE" |

This book by Edwin A. Grosvenor, professor of Latin and Greek in Istanbul at Robert

College, was apparently begun in the 1870s but printed in 1895, in a two-volume set; below

are pp. 48-9. National Geographic Magazine was started by Grosvenor's son.

At noon Sultan Muhammed II, the Conqueror, made his triumphal entry, and proceeded slowly

through the city by the later Triumphal Way to Sancta Sophia. The cymbals and gongs

resounded without cessation along the route; their every note was proclamation that the

Second Epoch of Constantinople had ended, and that the Third Epoch was begun.

THE THIRD EPOCH

If the transition of Byzantium to the Second Epoch had been enormous, that of

Constantinople to the Third was greater still. The moment the last Cacar’s fall left her

without an empire and head, she became the capital of the Sultans. Even in the new name

by which hereafter she was commonly to be called — in the name Stamboul or Istamboul [1],

fashioned in Turkish derivation from Constantinople — lingered the tale of her lofty

origin. Another name, Constantinieh, the most frequent on Turkish coins and of

constant use Arabs, Persians, and Ottomans, preserved the memory of her emperors. Save in

these two respects, — municipal rank and source of name, — all else was absolutely

changed, not only in outward form, but in individual essence.

The Romans and the Greeks had been of kindred blood, tracing their languages to a cognate

source. In the childhood of their race they had worshipped at the altars of common pagan

gods, and in their fuller manhood together abjured paganism for a higher and a diviner

faith. Their civilization had flowed from neighboring fountains, whose waters mingled

inter in a common stream. Eventuality at Constantinople the Roman element had disappeared,

had been absorbed, costume, language, contour of brow, color of hair and eye, tint of

skin, natural disposition even, into the entity of the Greeks. Yet it was not all

forgotten, for the name survived in the appellation of their language, Romaic, the

medieval Greek, and in the title by which they call themselves even to-day, the Romaioi.

But between the Ottomans and the Greeks there was not a link in common save a common

humanity. The host that appalled the ravished city with its frenetic shouts had come in a

slow march of the hundred and fifty years from beyond the Caspian, beyond the Great Salt

Desert, from the wide wastes of Khorassan. The robes they wore; the steeds they bestrode,

the arms they used so well, told of the distant East. The palaces they summoned into

existence for sultan and pasha, in structure and appearance recalled the patriarchal tent

and the nomad life of the plain.

1 One derivation often given for Stamboul is from … (ees teen poleen),

“to the city.” It is supposed that the Ottoman often overheard this phrase on the lips

of the Greeks, and that from it they formed the word Stamboul. This derivation is

untenable, The Ottomans often retained foreign name of places they had captured. In case

the name was long, they dropped the first syllable, and contracted or abridged the last

syllables. Thus from Thessalonica they made Selanik; from Constantinople, Stamboul.

(Thanks to Sukru Aya.)

|

|