|

|

Turkey has had a long history of

protecting Jews; precisely why the nation's Sephardic Jewish population was

loyal until the end. Here are a few examples of how Turkish

diplomats lent a much needed hand to Jews during the dark days of the Second

World War.

|

|

|

| Holocaust

Survivor Says Turkish Muslim Saved His, Other Jews' Lives |

Rudi Williams, American Forces Press Service,

WASHINGTON, April 23, 2002—As

a child on the island of Rhodes in the Aegean Sea, Bernard Turiel remembers listening to

his parents and their

friends talk about Jews being executed in concentration camps in Germany and Europe.

Turiel remembers the horror stories about Jewish people's skin being made into lampshades

and their bones being used to make soap. "These kinds of discussions left a fear and

horrid impression on all of us," he said.

Turiel survived the Holocaust, he said, thanks to

Turks on Rhodes and because he and his family were Turkish citizens. During "Honoring

the Turkish Rescuers," a special program held recently

at Washington's Lincoln Theater, he talked about his World War II childhood experiences

and how a Muslim saved his family and many others.

Rhodes today is Greek. From 1912 until 1945,

however, the Aegean island, just off the southwestern coast of Turkey, was an Italian

possession.

Italian dictator Benito Mussolini joined Germany

in the war in 1940 and invited his ally to garrison troops in Italy and its possessions,

including Rhodes, Turiel said.

He said the island in the 1920s and 30s had a

flourishing Jewish community of about 5,500 Jews out of a population of about 35,000.

Although many Jews fled in the 1930s, those who remained on Rhodes were harassed by the

Italian administration but relatively safe until Mussolini was deposed in July 1943 and

Italy's provisional government declared an armistice with the Allies. The Germans used the

confusion to overwhelm their one-time allies and seize control the Italians'

"empire" in September 1943, he added.

"When the Germans took over, the adult males

were asked to report to the headquarters offices," Turiel said. "That created

great concern as to what was going to happen." The men were told to

register and go home. This created a sense of relief, but also one of false security. When

the Germans began rounding up Rhodes' Jewish community in July 1944, the men reported to

the German headquarters again, Turiel said, but this time they were immediately

incarcerated. Turiel and his father and brother were among the incarcerated. Two days

after being detained, the men were standing in line waiting for transport to the continent

and a concentration camp, Turiel recalled.

|

|

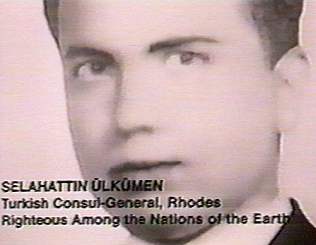

Selahattin

Ulkumen, from DESPERATE HOURS |

Enter 30-year-old Turkish Consul Selahattin

Ulkumen, who approached the German general in charge and demanded that all Turkish

subjects be released. He went further, demanding the spouses of Turkish citizens be

released, invoking Turkish law that anyone married to a Turk is a Turk. The Germans

assented.

Ulkumen was playing a dangerous game. He bluffed

the Germans — there was no

such law. "He was fully aware of the dangers for the Jewish community in Europe and

made a valiant effort to save as many Jews as possible, including non-Turkish

citizens," Turiel said. "He told my mother to go home and that our father would

be released. My brother and I had acquired Turkish citizenship and had dual

citizenship."

Ulkumen's bold personal action is credited with

saving 42 families. But his bluff didn't go unanswered. The Germans bombed his home in

retaliation. His wife, nine months' pregnant, was seriously injured and died of her wounds

while giving birth to the couple's son, Mehmet. Turiel said 643 of Rhodes' Jews were

deported to Auschwitz; all but 151 were exterminated or died in the labor camps.

Ulkumen left Rhodes in August 1944 when Turkey

ended diplomatic relations with Germany. Again, Jewish men were ordered to report to

German authorities, Turiel noted. Only a handful still lived on the island. Turiel said

the island was isolated, and the Germans by this time seemed more concerned about survival

than victory.

"They permitted us to eventually leave the

island in January 1945," said Turiel, a lawyer, who worked for the Federal Trade

Commission from 1959 to 1966. He's now an attorney in private

practice in northern New Jersey.

The Turiels left Rhodes for Turkey in January 1945

and emigrated to the United States in July 1946. Turiel's father joined his two brothers

in their import-export business.

Turiel told the Lincoln Theater audience that

Ulkumen was a man of great determination, courage and compassion. On June 11, 1988, the

Anti-Defamation League presented Ulkumen its fourth annual "Courage to Care"

award.

"He was brought to New York for the

presentation and we were reunited with him," Turiel noted. "My mother maintained

correspondence with him over the years."

|

|

Selahattin

Ulkumen (1914-2003) |

In June 1990, Ulkumen was installed on the Avenue

of the Righteous Gentiles at the Yad Vashem in Israel. "What used to be known as the

Righteous Christians has been changed to the Righteous Gentiles because Mr. Ulkumen was

the first non-Christian to receive the award. He is a Muslim," Turiel noted.

"Mr. Ulkumen will always be remembered as a

courageous, compassionate and righteous person," Turiel said. "Today, he's frail

and living in an old age home in Turkey."

Turiel said he and his family and other Holocaust

survivors are extremely fortunate to have come to the United States.

"We're grateful to live in this wonderful

country where our forefathers had the great forbearance to think of the great democratic

country and the need for a Bill of Rights," he said. "The Bill of Rights

has provided the type of government and style of life that we enjoy and cherish. We never

take it for granted. Having experienced our lives in Europe, we're most grateful to be in

such a wonderful

country as the United States."

Web site honoring Mr. Ulkumen: www.ulkumen.net

|

RESCUE OF EIGHTY JEWISH TURKS

|

NECDET KENT’S RESCUE OF

EIGHTY TURKISH JEWS IN MARSEILLES, FRANCE

FROM HITLER’S GERMANY

(Editor’s Note: Jak Kamhi, a Turkish Jew, and prominent businessman in Istanbul

located Necdet Kent [now a retired ambassador] and obtained his personal account of

his rescue of some eighty Turkish Jews in Marseilles, France from Hitler’s

Gestapo. This deposition has been translated by Ayhan Özer and is reprinted below as an example of the proud

Turkish historical record of saving Jews from persecution and death.)

In 1941, I was assigned by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Turkey as Vice-Consul

to the city of Marseilles of France. During my tenure I was promoted to the rank of

Consul, and I left Marseilles in 1944. In this post I reported to three Consul

Generals in the following order: Mr. Bedri Arbel, Mr. Munir Pertev Subay, and Mr.

Fuat Carim (All three passed away).

|

|

Necdet

Kent, from DESPERATE HOURS |

At that time in France there were two kinds of Turkish Jews. One group

consisted of those Jews who came to France at the end of World War I with the French

occupation forces in Turkey. Those Jews either did not have any Turkish passport, or

even if they did they had expired a long lime ago. The only official document they

had possessed was their birth certificate in Arabic script that they had obtained

from the Ottoman State. Technically, the Turkish consulates regarded those Jews as

“non-citizens”. The French governments before World War II had been lenient on

this matter and condoned their situations. As a result, the Jews in this category

have never bothered to apply to the Turkish consulates or Embassy to regularize

their status. Those in the second category comprised the Jews who had left Turkey

with a valid passport, but at the outbreak of World War II they had not returned,

and stayed in France. These Jews were regarded as “regular” Turkish citizens.

When Northern France had been occupied by Nazi Germany, along with the indigenous

population the Turkish Jews as well made an exodus to the South, and came within our

jurisdiction. The French authorities dubbed the non-French refugees as “Repliés”

(In English retreated or receded). The situation in the South was far from being

comfortable at that time, but when the German troops invaded southern France as well

it became oppressive.

As soon as the Nazis took control of the region they began to search for the Jews

and made arrangements to transport them to Germany in trains. At this time we

received occasional complaints from the Jews who were Turkish citizens, which

prompted us to take some action.

We made an appeal to all the Jews to apply to the Consulate in order to legalize

their status. If the status of the Jews who had applied to our Consulate was

regularized, we immediately issued a certificate of citizenry. If they owned any

businesses, stores, etc., we admonished them to display in a prominent place of the

premises a notice that we provided. This notice stated that the owner of the

establishment was a Turkish citizen, and that the premises and its contents were

under the protection of the Republic of Turkey. In the cases where the status of the

Jews was not regularized, we asked them to fill out an application form, and issued

a temporary certificate as testimony to their Turkish citizenship, which also

advised the authorities that the official documents of the person concerned were

being processed, and that the permanent papers would soon be issued to replace the

interim certificates. These measures proved helpful and protected several Turkish

Jews against troubles.

There have been times that our Consulate staff called on the Gestapo headquarters

(sometimes three or four times a day) to solicit the release of our Jewish citizens

who had been detained. Most of the times these efforts entailed persuasion, but

sometimes we had to utter subtle threats to take up the matter with higher

authorities. To make matters worse, the Italians as well had started to emulate the

Germans and applied similar practices in their regions. At times we had arguments

with the Italian consul to persuade him to stop this inhuman treatment of the Jews.

I later learned that my efforts had borne fruit to some extent.

In one instance the anti-Jewish obsession manifested by the Gestapo reached

dimensions that defied human dignity. For a while the military patrols had started a

new practice to identify the Jews. This involved stopping the men whom they had

suspected to be Jews right on the street, and making them drop their pants to see

whether they were circumcised. This exercise led to the arrest of several Jews, as

well as Muslim Turks. Many of them indiscriminately were taken to detention centers

for a summary transportation to Germany. To protest and to put a halt to this

ill-advised practice, I immediately went to the Gestapo Headquarters, and explained

to the commandant that being circumcised had nothing to do with being a Jew. From

the empty stare in his eyes I figured that he had not understood what I meant.

Thereupon, I requested that a doctor examine me to further clarify my point. This

came as a revelation to him, and he agreed to release several people.

The climax of all these efforts, however, came about in a showdown with the Gestapo

authorities during a period of time when the Consul General was on leave and away

from the office. One night, one of our employees, Sidi Iscan, a Turkish Jew from the

city of Izmir, who was at the same time a translator in the consulate came to my

home unexpectedly. (Sidi Iscan also passed away). He appeared to be in fear and

agitated. In tears, he told me that the Germans had rounded up some 80 Jews in the

city and took them to the train. I tried to calm him down, and assured that we would

do something about it. We immediately went together to the Gare Saint-Charles, the

main train station of Marseilles.

We approached the train and observed the situation for a brief moment. The sight was

indeed beyond any imagination. We heard crying and moaning sounds coming from inside

the boxcars. Through some partly open sliding doors we saw human beings crammed in

the wagons. On the side of the cars I noticed the following words:

“This car holds 20 cattle and 500 kilo of feed.” My anger and desolation were

overwhelming. I requested an explanation from the responsible person, whoever he

was, for this undertaking. The Gestapo officer in charge came to the scene, and in

an overbearing tone he demanded to know the reason for my being there. Restraining

myself to remain within the limits of diplomatic courtesy, I told him that there

must have been a gross error, a misunderstanding, because those people were Turkish

citizens, and I demanded that he rectify this situation immediately. The Gestapo

officer told me that he was merely carrying out the order he had received. Besides,

he said, he was sure that those people were not Turks, but Jews. From his tone and

attitude I sensed that he was adamant and not willing to make any concession.

|

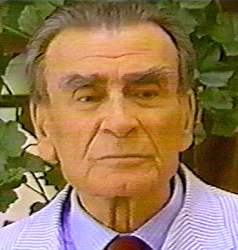

|

Necdet

Kent (1911-2002) |

Thereupon, I turned to Sidi Iscan and told him

to follow me, and to get on the train, because we were going in that train as well.

We proceeded to the train with resolve. The Gestapo chief obviously had not

anticipated this move, he tried to convince us to leave the train, but I refused to

listen to him. Shortly afterwards the train pulled out slowly from the station. When

we arrived in Aries or Nimes the train stopped. We saw a number of German officers

getting on the train. They directly came toward me. After a brief and cool exchange

of salutation, the highest ranking officer said in an apologetic tone that there had

been a misunderstanding when the train departed while we were still on board, and if

we left the train at that time they would provide us with transportation (their own

Mercedes-Benz) back to Marseilles. It was an intimation to us that we had to accept

whatever they offered at that time, and any further concession was beside the point.

Yet, on my part I knew that the country I represented was the only hope of those

eighty some innocent Jews, and I could not bring myself to see them go to their

sinister destiny without exhausting all efforts. With this conviction I maintained

that his proposal was unacceptable to us, we had a mission which was to obtain the

release of all those innocent Turkish citizens who had been crammed into cattle cars

on the ground that they were Jews. This act was against the Turkish traditions which

uphold that no humanitarian norms would justify such discrimination, and as a

representative of the Turkish Republic my duty was to protect them to the end. This

critical argument was carried on in an emotionally charged atmosphere, and was being

followed intensely by some Jews in the vicinity. They were aware that the outcome of

this crucial negotiation would determine their fate.

In the face of my intransigent attitude,

perhaps considering the consequences of a possible political contre temps with

neutral Turkey, the officer invited me to declare officially that all those in the

train were Turkish citizens. I somehow felt a flicker of hope, perhaps a turning

point in the whole episode. I readily and solemnly made the declaration he

requested. Thereupon all the German officers left the train, a few minutes later we

followed. When we at last saw them leaving the scene in their cars, we realized that

it was freedom. I will never forget the emotional moment that followed. All of the

freed passengers came to embrace me, held and shook my hands fervently with an

unforgettable expression of gratefulness in their watery eyes. We immediately made

arrangement for all of those people to return to their home. It was almost daybreak

when I arrived at my home. It had been a grueling day but I slept with a deep

contentment that I had never felt before. For years afterward, I received several

cherished letters from the passengers of that fateful journey. Perhaps many of them

are no longer living, but I remember them with deep affection.

Necdet Kent Ambassador (Retired)

THIS DEPOSITION

WAS RECEIVED BY:

Mr. Jak V. Kamhi

President

Profilo Holding A.S.

ATA-USA Winter 1989

|

| Help From Turks

During Desperate Hours |

Columnist Tufan Turenc writes on the documentary recently reported

on by CNN entitled 'Desperate Hours' detailing the help given by Turks during World War

II. A summary of his column is as follows: "In 1933 when the Nazis came to power and

Hitler assumed Germany's leadership, democrats in Germany and particularly German

citizens of Jewish descent were greatly troubled. Scholars were frightened. Mustafa Kemal,

who was closely following the developments in Germany, felt the coming of the tragedy

Hitler was going to inflict upon the world.

Without losing any time, he gave instructions that scholars of

Jewish descent be invited to our shores. More than 200 academics came to Turkey, which

welcomed them with open arms. The Turkish Republic, which faced many problems at the time,

appointed these academics to universities with high salaries. Through the efforts of these

gifted visitors, the quality of education in Turkey got an immediate boost. After their

long stay in Turkey and with the end of Hitler's reich, these academics returned to their

countries. However, none of them forgot Turkey's noble gesture, and they saw our country

as their second homeland. At the beginning of the 1940s, Turkish diplomats prevented

the taking of thousands of Jews to concentration camps through the exertion of great

efforts. This exemplary action of the Turkish Republic and its diplomats was revealed

in a documentary recently prepared by Jews living the US. This striking documentary was

just promoted in CNN International. At a time when we are being suffocated with

publications and programs slandering Turks and Turkey with countless lies, such a

documentary makes one proud. This documentary should be a lesson in humanity to those who

are trying to use history to wreak revenge and foster hostility."

The screening of "Desperate Hours"

Hon. Tom Lantos of CA in the House of Representatives

(Extensions of remarks, May 20, 2002)

Mr. LANTOS. Mr. Speaker, I am honored today to mark a special

occasion, the screening of the film documentary "Desperate Hours," the story of

Turkish assistance to European Jews seeking

to flee the Holocaust. Produced and directed by Victoria Barrett, the film will be shown

at 7:15 p.m. in room HC-7 in the Capitol. I am proud to be a co-sponsor of this event.

Mr. Speaker, I first visited Turkey as a young man in 1956. My wife

Annette and I have returned to enjoy Turkish hospitality many times since. When I first

visited Turkey, it was just a few short years after Turkey had made the crucial decision

to join NATO, where it has always been a loyal Western ally, first against Soviet tyranny,

later against ethnic cleansing in the Balkans, and now against global terrorism.

But what most ennobles Turkey for me is Its role as a savior of so

many Jews during the two greatest Jewish tragedies of the past millennium, the Inquisition

and the Holocaust. During the

Inquisition of the late fifteenth century, the Ottoman Sultan Bayezit invited the fleeing

Jews of Spain and Portugal to find comfort in his realm. The 500th anniversary of this

episode--both sad and redemptive--was marked by Turkish Jews and non-Jews alike in 1992.

The documentary "Desperate Hours" commemorates Turkey's

rarely cited role in that other Jewish tragedy--the greatest crime of the bloody twentieth

century--the Holocaust. Turkey's efforts were as important and dramatic as they are little

known. Turkey offered refuge to hundreds of Germans--non-Jews as well as Jews--during the

1930s. Its diplomats in France, often without waiting for instructions from the capital,

conferred Turkish citizenship on thousands of desperate Jews trapped in Nazi-occupied and

Vichy France. In some cases Turkish diplomats, at great personal risk, stared down Gestapo

officers to protect their new fellow citizens, as was the case with the saintly Necdet

Kent. All this, while Nazi troops stood poised on Turkey's borders.

My wife and I were saved by Raul Wallenberg. I am pleased that the

Turkish versions of Wallenberg are at last receiving their due.

The intimate links between Turks and Jews continue, of course, to this day. A community of

some 25,000 Jews thrives in contemporary Turkey. Tens of thousands of Turkish Jews living

nearby in Israel cherish their links to Turkey. All of this is a testament to the

Muslim-Jewish friendship that has been a hallmark of the Turkish historical

experience.

In recent times, Turkish-Jewish friendship has been enriched and

deepened by the close relations Israel and Turkey have forged in recent years. Journalists

have focused on the security relationship — and that indeed is important — but the non-security aspects of this

relationship are growing even more rapidly: burgeoning commercial trade now worth over a

billion dollars a year, Israeli tourists by the hundreds of thousands flocking

annually to Turkey, and a vibrant intellectual exchange between Turkish and Israeli

universities.

No other Muslim society rivals Turkey's record regarding the Jews;

in fact, few societies of any type anywhere in the world do. I congratulate my dear friend

former Ambassador Baki Ilkin, who

so strongly supported this documentary project, and my dear friend the current Turkish

ambassador Faruk Logoglu. I strongly commend all those associated with the film

"Desperate Hours" for helping to elucidate and publicize one of the most

important chapters in the long, dramatic, and mutually rewarding history shared by the

Jewish and Turkish peoples.

Turkey's version of Schindler's List

Documentary brings Turkey's version of Schindler's List out into the light

Muslims, Jews and Christians work to save lives in Desperate Hours,

filmmaker says

IRWIN BLOCK

The Gazette

Wednesday, February 11, 2004

Documentary filmmaker Victoria Barrett talks about her award-winning Desperate Hours, a

film about Turkey's role in saving European Jews from the Holocaust. It will be shown

tonight in Montreal, and broadcast for the first time in North America tomorrow.

Among acts of conviction and bravery to save imperiled Jews in German-occupied Europe, few

people know of the Turkish heroes of the Second World War.

Meet Necdet Kent, the Turkish consul in Marseille, France, during the dark days of the

early 1940s.

Some call him the Turkish Oskar Schindler for what he did to rescue Jews of Turkish

origin.

Turkey at the time was neutral; Kent and two other Turkish diplomats are estimated to have

saved 10,000 Turkish Jews by insisting the Germans respect their Turkish nationality.

Another 10,000 Jews from Romania and Hungary may also have found refuge in Turkey during

that time.

And it took an Episcopalian from the Shenandoah Valley in West Virginia to record on film

the saga of the Marseille rescue and similar acts of extraordinary humanitarian effort.

|

|

Victoria

Barrett |

Filmmaker

Victoria Barrett produced the award-winning documentary Desperate Hours, which will be

broadcast for the first time in North America tomorrow on PBS Mountain Lake at 8 p.m.

What drove her to record this chapter in history?

"Today I don't think there is any greater problem facing the world than religious

intolerance," she said in an interview in Montreal.

"This movie tells stories of Muslims, Jews and Christians are working to save lives,

not to kill each other."

Barrett's film will also be shown at the Musée d'Art Contemporain tonight, when Turkish

ambassador Aydemir Erman will be awarded the B'nai Brith interfaith humanitarian award for

Turkey's role in saving Jews.

Discussing the Marseille incident, she noted: "In the middle of the night, someone

comes running into the consulate to say they've rounded up all the Turkish Jews, they're

on a train and they're taking them to one of these camps.

"Necdet Kent got out of bed, he went to the train and sat there as the train left and

travelled with it 60 kilometres.

"Finally the German officer said, 'OK, fine, you can take your people and go. We

don't want an incident.' "

The effort is believed to have saved an estimated 50 to 70 people from certain death.

Barrett's timing was prescient, as all three diplomats, including Namik Yolga in Paris and

Selehatin Vikemen on the island of Rhodes, have died since being captured on film.

"Unbelievable. I'm so glad," said Barrett, an actor who happened to be living in

Turkey when she learned of these little-known deeds and decided to make them the subject

of a documentary.

The film, chosen best documentary at the 2003 Washington Independent Film Festival, relate

other Turkish efforts.

Turkey welcomed 200 German and Austrian academics, two-thirds of whom were Jewish or

partly Jewish, and were forbidden from teaching in 1934.

"Albert Einstein was heading for Turkey, but he got a better offer in the U.S.,"

Barrett remarked.

A surviving professor and several descendants praise Turkey for saving their lives.

In 1941, when the Germans were 80 kilometres from Istanbul, Turkey blew up two bridges to

retard possible invasion. Some Jews moved to Anatolia.

Montreal Gazette

|

Namik

Kemal Yolga

|

Namik Kemal Yolga (1914-2001)

was a Turkish diplomat and statesman , known as the Turkish Schindler . During the

WWII, Yolga was the Vice-Consul at the Turkish Embassy in Paris, France . His

efforts to save the lives of Turkish Jews from the Nazi concentration camps earned

him the title of "Turkish Schindler."

|

|

Yolga

(1914-2001) |

Namik Kemal Yolga was posted to

Turkish Embassy in Paris in 1940 as the Vice-Consul, his first diplomatic post in a

foreign country. Two months later Nazis invaded France and started their hunt for

the Jews and sent them to a concentration camp in Drancy near Paris. Young Yolga was

brave enough to save the Turkish Jews one by one from the Nazi authorities, drive

them in his car and hide them in safe places. Yolga's determination resulted to save

all the Turkish Jews except one who was later transferred to a concentration camp in

Germany. In his autobiography, Yolga described his efforts as: "Every time we

learnt that a Turkish Jew was captured and sent to Drancy , the Turkish Embassy sent

an ultimatum to the German Embassy in Paris and demanded his/her release,

specifically pointing out that the Turkish Constitution does not discriminate its

people for their race or religion, therefore Turkish Jews are Turkish nationals and

Germans have no right to arrest them as Turkey was a neutral country during the war.

Then I used to go to Drancy to pick him/her up with my car and put them in a safe

house. As far as I know, only one Turkish Jew from Bordeaux was sent to a camp in

Germany as the Turkish Embassy was not aware of his arrest at the time."

The foregoing is from Wikipedia (BEWARE!)

|

| "The Ambassador" Saves 18,200 |

The story of “The Ambassador” or Behiç Erkin:

Behiç Erkin's grandfather was an Ottoman Army Commander. Despite the fact that Erkin was

disabled, he was accepted to the Ottoman Army because of his grandfather's position and he

became the only individual to receive "special authorization" to join the

Ottoman Army Corps of Officers.

|

|

Behic Erkin,

from WWI days with gold cross |

Erkin was appointed Thessalonica Military Railroad Commisioner and

met Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the founder of the Turkish Republic, in 1907. He became one of

Atatürk's closest friends and confidants throughout his lifetime.

During the Gallipoli War, Erkin was responsible for successfully transporting logistics

and military personnel to the front, for which he was awarded the German Gold Cross (First

Degree), the highest award given by the Germans and French Legione D'Honneur (First

Degree).

Erkin was asked by Atatürk to head the newly formed Turkish Railroad Administration

during the War of Independence. It was one of the most important and vital posts for the

war years as it shouldered the transportation of army and logistics to various fronts

during the war.

Atatürk gave Behiç his last name, "Erkin," which means independent, on Feb. 8,

1935 and said, “When Behiç has a firm conviction, even I can't change his mind.”

After the War of Independence, Erkin was awarded the "Independence Medal." He

became a member of the newly established Parliament and later the Public Works Ministery.

After the death of Atatürk in 1938, İsmet İnönü came to power and İnönü

sent Erkin to France as Turkish ambassador to Paris. During his tenure, which coincided

with the Nazi occupation in France, he ensured that Nazi officials did not confiscate the

properties of Turkish citizens of Jewish origin living in France.

The registered number of Turkish Jews was about 10,000 but there were about 10,000

unregistered Jews, whose origin can not be identified as to whether they were Turkish or

not.

He opposed the French authorities and granted Turkish citizenship to those who called

themselves Turkish under the pressure of Nazi occupiers who wanted to send the Jews to

concentration camps. He used his golden German medal and personal courage and knowledge to

help secure the return of Turkish Jews.

In order to prevent the French security forces from apprehending the Jews of Turkish

origin from their domiciles, he threatened the French by saying he would have Turkish

flags hung up in front of every house therefore providing diplomatic immunity.

The ambassador provided the safe return of over 18,200 Turkish-Jewish citizens living in

France out of 20,000 by train. Nowhere else did members of the Jewish community survive in

such large numbers under Nazi occupation.

The above is an excerpt from the Feb. 13, 2007 issue of the Turkish

Daily News, and the rest may be read here. It appears Hollywood is interested in "The

Ambassador," a book written by Erkin's grandson, the product of nine years of

research. George Clooney is reported to be considering the role.

Prof. Stanford Shaw, in his book "Turkey and the Holocaust," wrote of 10,000

Turkish Jews, 10,000 irregulars (possibly Turkish Jews, but maybe not), and 400 others for

a total of 20,400. It's pretty remarkable the ambassador saved over 18,000. vs. (for

perspective) Schindler's 1,000.

Unfortunately, many Jews are totally ignorant of the

great deeds of one of their very, very few historic good friends. This is one reason why

so many of the ignorant ones don't think twice before hopping in the same bed with beloved Armenians.

|

|