|

|

An anti-Ataturk

jeweler in this New York Times article is quoted as

saying, "They don’t want our women to wear headscarfs. But why shouldn’t

they? Isn’t that democracy?” He's right... unfortunately, things aren't as

simple as all that. Once the dogma of fundamentalism takes hold, it would be a

giant step backward for any nation. The greatest allies of Armenians and

Greeks are the cobweb-minded Islamists of Turkey, who only came into being in

the 1980s with the stupid decision to accentuate religious schools. Just as

these medieval minds played a strong role in leading to the demise of The

Ottoman Empire, they are poised to do so again in the more modern version of

their nation... if given half a chance.

The Second article is

entitled "The Menace Of Religious Zealotry," exploring the question

of fundamentalism increasingly directing global politics.

|

|

|

| The Alarming Scarf

and Other Turkish Worries |

Safranbolu Journal

The Alarming Scarf and Other Turkish Worries

The New York Times

October 29, 1998

By STEPHEN KINZER

SAFRANBOLU, Turkey, Oct. 25 —

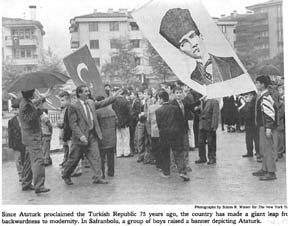

Festive banners fluttered from lampposts and windows as a troupe of young folk dancers

prepared to mount a makeshift stage here on Saturday morning. Like tens of millions of

Turks across the country this week, they were joining in celebrations of their country’s

75th birthday.

|

|

Since Ataturk proclaimed the

Turkish Republic

75 years ago, the country has made a giant leap

from backwardness to modernity. In Safranbolu, a

group of boys raised a banner depicting Ataturk.

|

One dancer, Gulcan Eran, 16, seemed a symbol of Turkey

itself. She is thoroughly modern and Western-oriented, vibrant, self-confident and

ambitious for a career as an engineer. But as Ms. Eran adjusted her resplendent costume,

two young women wearing traditional headscarfs walked across the plaza nearby. She turned

serious.

“I wouldn’t object if the scarf was just about religion, but it isn’t anymore,”

she said. “It’s a political uniform. It’s a way of saying that you want to get rid

of the secular republic. I think it’s very dangerous.”

Turks who are gathering this week for festivities ranging from poetry recitals to

kick-boxing matches have reason for self-congratulation. Their country has made a giant

leap from backwardness to modernity in 75 years, and the nearly two dozen foreign leaders

due at the central commemoration in Ankara on Thursday reflect its role as a regional

power.

But as Turkey seeks to establish a stable democracy for its 65 million people, it also

confronts several persistent problems. Defining the role of religion in public life is

only the most visible.

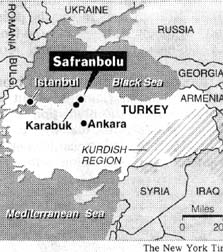

Both Turkey’s achievements and its looming challenges are clearly visible here in

Safranbolu, a pleasant town of 20,000 nestled in the rocky Anatolian plateau. It is known

for its 19th-century Ottoman buildings, and attracts a modest stream of tourists. Some

residents till small farms on outlying hills. Others work at a steel mill in nearby

Karabuk that offers employment to thousands but also casts a rancid cloud over the town.

The streets here are tree-shaded, houses are

sturdy and well kept, schools are full and clinics modern. Shops offer all manner of

domestic and imported goods.

“We’ve made a lot of progress in 75 years,” said Ozcan Cakir, 45, manager of a small

candy factory in Safranbolu. “This will never be a backward or Middle East-type country

again. But I worry about the future. There’s hunger in Turkey. I can afford to send my

kids to college, but people who work for me can’t. That produces resentment, and in 10

or 15 years that resentment could bring trouble.”

Several portraits of Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, who proclaimed the Turkish Republic on Oct.

29, 1923, decorate Mr. Cakir’s salesroom. They mark him as a dedicated supporter of the

secular order. But at the jewelry store next door, there is no Ataturk portrait.

“Twenty-five percent of our peoplc don’t support this kind of secularism,” said the

jeweler, Ahmet Pulcu, suggesting that he is among them. “The rest have no idea what

religion is. They don’t want our women to wear headscarfs. But why shouldn’t they? Isn’t

that democracy?”

|

|

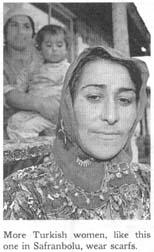

Scarf-wearing

woman

|

|

In Safranbolu, as in many Turkish cities and

towns, measurably more women wear headscarfs than wore them only a couple of years

ago. It is a sign of growing religiosity that the Islamic movement encourages. But

it disturbs some secularists, among them military officers. Turkish universities

have banned the wearing of headscarfs by female students, giving Islamic politicians

a vivid issue. They are crisscrossing the country telling voters that their

daughters are being excluded from tax-supported universities simply because they are

devout Muslims.

The air force commander, Gen. Ilhan Kilic, vowed recently that the military would

fight every effort aimed at “undermining this system and turning the country into

an anachronism.” Many Turks say that this uncompromising attitude guarantees the

survival of the secular republic. But others fear that it is polarizing the nation

and perhaps setting the stage for confrontation.

Turkey also confronts the question of how to deal with its large Kurdish minority.

That issue is also palpable in Safranbolu.

On a hillside just a few minutes’ walk from the town center is Safranbolu’s

Kurdish quarter. To enter it is to pass from the developed world into poverty.

The town’s 700 Kurds live in ramshackle cabins without running water. Many are

dirty, poorly dressed and have open sores on their faces or arms. Almost all are

unemployed.

“We’re Turks, but second-class,” said Bilal Cetinceviz, 65, a community

leader. “People don’t like us or don’t trust us. When we apply for jobs, we

don’t get hired. Our kids don’t go to school because we can’t afford to buy

them books and clothes.”

“When you have no work, you have nothing to lose,” Mr. Cetinceviz said. “Every

once in a while some radical Kurd shows up here and tries to turn us into militants.

We throw them out, but if we didn’t, in six months everyone here would be a

militant.”

Many Kurds in Turkey have risen to leading positions, but many others have been left

behind by the country’s economic boom. While coastal regions thrive, the mainly

Kurdish southeast is impoverished.

Kurdish guerrillas have been fighting a separatist war there for 14 years. Thirty

thousand people have been killed in the conflict. It costs an estimated $8 billion a

year to wage, and ties down more than 200,000 Turkish soldiers.

|

|

|

|

Turkey’s achievements and

challenges are visible in Safranbolu.

|

|

The questions of poverty. religious fundamentalism and Kurdish

identity hang over Safranbolu as they do over the rest of Turkey. Over the last two years,

however, a new topic has emerged at cafes and teahouses.

Spectacular disclosures about ties between gangsters and the Government have shaken public

faith in the political system. Phrases like “black money” and “state gangs” are

now part of everyday conversation.

The spreading scandal has produced grave allegations against several of the country’s

past and present leaders, but investigations have been limited. Magistrates do not have

unfettered freedom to pursue cases against political figures. Cynicism is growing, even

among many who until recently refused to believe that agencies of their Government could

ever have sponsored death squads or tolerated smuggling or other crime and gangs,” said

Aybar Toker, the local soft drink bottler. “People think all the established parties are

involved, so they vote for the Islam party as a protest.”

If Turkey’s greatest challenge in the years ahead is to forge a nations consensus over

how to establish full democracy here, it must have political leaders who can lead the way.

Yet many Turks believe that the political system is closed to them. Parties are run by

bosses who tolerate little dissent, and as a result many talented men and women shun

politics in favor of business, academia or journalism.

“It’s true that our political system is very closed, but business people are beginning

to take a much greater role in society, and they aren’t bound by all these taboos,”

said Yuksel Oktay, 61, an American-educated engineer who grew up in Safranbolu and visits

periodically. “I also see a great potential in our youth. They understand what is at

stake here, and they won’t let Turkey slip backward.”

“We have problems, but I think most Turks would be optimistic about our chances of

solving them,” Mr. Oktay said. “I certainly am.”

|

The Menace Of

Religious Zealotry

|

The Menace Of Religious Zealotry

Fundamentalism Increasingly Directs Global Politics.

Is Compromise Going To Be A Thing Of The Past?

By Kevin Phillips

copyright 1998 Los Angeles Times

Fifty years have passed since Winston Churchill made his speech observing that, from

Stettin on the Baltic to Fiume on the Adriatic, an Iron Curtain was dividing Europe.

Not any more. But now a new potential divide is becoming visible in Europe and Asia.

Religious zealotry is one hallmark of the escalating confrontation between the West

and a number of Muslim nations along a line from North Africa to Malaysia and

Indonesia. Radicalism in many religions is as obvious in parts of Brooklyn, Chicago

and South Carolina as in Turkey and Algeria, but Islamic fundamentalism is growing

the fastest and has the best prospect of intrafaith gains.

Like crusading Catholicism in the Middle Ages and the aggressive Protestantism of

the Reformation, militant

Islam is not simply aroused by its own cause, but also is responding to the

hostility of the existing Muslim power structure — from old-guard Persian Gulf

emirs to progressive secular Turks — and the all-too-frequent cultural and

economic arrogance of the West. Throw in evidence of China and the overseas Chinese

being frequent Muslim allies, and the looming 2lst century geography is as powerful

as the cultural fit and the population numbers.

The Chinese and Muslims together now have double the West’s share of world

military manpower, after trailing at the end of World War ll.Though the West

currently has twice their combined economic strength, its key remaining bulwark,

some Chinese-growth projections suggest that could fade by 2020.

Harvard Professor Samuel P. Huntington has predicted that culture and religion will

shape the new century’s clash of civilizations. If so, forget the Maginot Line of

World War II. To paraphrase the great battle hymn of Reformation Luthranism:

The new mighty fortresses may be our gods. By 2009, we may have to worry about

whether World War III could start along the Minaret Line.

Just consider the Middle East. As recently as 30 or 40 years ago, rivalries there

were a mix of Arab-Israeli enmity, the legacies of colonialism — for example, the

British and French invasion of Suez in l956—and U.S.-Soviet Cold War jousting.

Since then, religious commitment and activism have surged. Fundamentalism is gaining

in most Muslim nations, save for Iran, mullah driven for so long that there seems a

slight thaw now.

Israel, in turn, has a government dominated by the Jewish equivalent of America’s

religious right:

Greenville, S.C., in yarmulkes.

Russian activism in the Mideast also seems increasingly influenced by the old

Orthodox nationalism of the czars. One academic expert, Edward L. Keenan, has

compared the rise of the religious right in Russia to that of Israel: In both, it

consists mostly of the poor and young reacting against Westernized elites.

In the United States, members of the Southern Baptist Church, the most

fundamentalist of the major denominations, dominate Washington politics: President

Bill Clinton, Vice President Al Gore and House

Minority Leader Richard A. Gephardt (D-Mo.) for the Democrats; House Speaker Newt

Gingrich of

Georgia, Senate Majority Leader Trent Lott of Mississippi and Sen. Strom Thurmond of

South Carolina

for the GOP.

None of these men takes the Bible literally, even if many fellow Baptists do.

Several have even whittled the 10 Commandments down to five or six. Nonetheless,

they’re well aware of the importance of the biblical lands in the Middle East to

U.S. voters: George Bush won 90% job approval with a successful war against a

regional tyrant. Through such calculations, religion is a powerful force in U.S.

Mideast policy.

What’s unnerving is the possibility that the biblical lands are part of a larger

zone of potential West-versus-Islam conflict that stretches almost 10,000 miles,

from the Atlantic beaches of Casablanca to the South China Sea.

A cook’s tour could begin in Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia and Moammar Kadafi’s

radical Libya. But the front-line hot spots, where Islam and the West are already

developing mutual bitterness, are big urban centers like Paris, Brussels, Frankfurt

and Berlin. Of the 12 million to 14 million Muslim immigrants in Europe—Moroccans,

Tunisians, Algerians and Turks—most crowd into these cities, nurturing radicalism

on both sides.

Further east, the 6 million to 8 million Muslims of the Balkans, a legacy from the

centuries of Ottoman rule, dominate Albania, as well as much of Bosnia and Kosovo

and part of Macedonia in the former

Yugoslavia, along with parts of Bulgaria. Fighting between Orthodox Christian Serbs

and Muslims is already widespread in Bosnia and Kosovo. A wider Balkan war with

essentially religious battle lines is quite possible. Cyprus, too, has again emerged

as a possible battleground between Greek Orthodox Chrstians and Turkish Muslims.

In and around the Holy Land, the secular Muslim states of Egypt and Turkey are also

in danger of being taken over by Islamic radicals. Either transformation could set

the region ablaze. Politics in Turkey

is particularly sensitive to how Turks and other Muslim immigrants face

discrimination in the ethnic ghettos of Western Europe, and how the European

Community is perceived as rejecting Turkish membership for ethnic and religious

reasons. The Persian Gulf is already incendiary, with the recent U.S. saber-rattling

against Iraq being taken in some quarters for hostility to all Muslims.

An additional stop on Islam’s armed frontier would be the Caucasus region, where

Muslim Chechens are fighting Orthodox Russians, and Christian Armenians are at sword’s

point with Muslim Azerbaijanis.

|

| |

Another problem area is in the largely Muslim republics of

what used to be Soviet Central Asia.

Several thousand miles across India and the Bay of Bengal, three Muslim-influenced

republics of Southeast Asia—Malaysia, indonesia and the Philippines—have their

political and economic noses out of joint from the recent financial collapses. Some

local leaders, including Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir

Mohamad, blame the West for using the currency crisis to erode local economic

sovereignty. It is not a baseless charge. In Indonesia, with 200 million people the

most populous Muslim nation, President Suharto has been obliged to accept

International Monetary Fund reforms. The resulting fuel, electricity and

transportation increases have led to riots.

Washington policy-makers, who are caught up in “Wag the Dog” threats and

policing Southeast Asian economies through IMF bureaucrats and mutual-fund managers,

should take another look. The West is on five distinct collision courses with Islam:

the explosive Muslim immigrant ghettos could disrupt half the major cities in

Europe; U.S. troops have been put in the line of ancient hatreds in Bosnia; war

threats in the biblical lands smack of fire drills for Armageddon; the suppression

of oil prices to 25-year lows strikes at Muslim economies from Nigeria to Indonesia,

and financial colonialism is a provocation.

Should any of these problems escalate, Islam isn’t likely to stand alone. China,

Asia’s other demographic Goliath, has been a frequent ally in areas such as

nuclear nonproliferation, and the two cultures make a good fit: Chinese commercial

and financial skills with the fervent radicalism of the Muslims.

Practical proof abounds. In recent decades, countries such as Malaysia, Indonesia

and the Philippines have shown how an overseas Chinese commercial elite can build

prosperity within a largely Muslim national population. China itself has tens of

millions of Muslims; even in Hong Kong, half the small Muslim minority is ethnic

Chinese.

Together, the two groups are predicted to have 30% of the world’s population in

2010, with just 12% for the West. Compare that to 1920, when the West had 48% and

the Sino-Muslim nations 20%.

A 21st-century U.S. confrontation with this axis could be disastrous. New York and

California have large segments of the Chinese diaspora. Of the 5 million Muslims in

the United States, the Harvard Pluralism Project advised in 1997, “The Islamic

World is no longer somewhere else... instead, Chicago, with its 50 mosques and

nearly half a million Muslims, is part of the Islamic world.” Not quite. Yet, the

average American of 1998 has little idea of what global geopolitics could be like in

2010 or 2020.

---

Kevin Phillips, Publisher of American Political Report, Is Author of

“The Politics of Rich and Poor.“ His Most Recent Book is “Arrogant Capital:

Washington, Wall Street and the Frustrations of American Politics.”

|

| |

|

|