|

|

I'm a big fan of Dr. Gwynne Dyer. My first exposure to

his work was his now classic "Turkish 'Falsifiers' and Armenian

'Deceivers'," which I deeply appreciated; it was the rare look at

both sides of the "genocide" equation by a qualified and objective

scholar, and a look that would not be significantly repeated until Dr. Guenter

Lewy wrote his sure-to-be-classic "The Armenian Massacres in Ottoman

Turkey: A Disputed Genocide."

Such an examination puts a real scholar between a rock and a hard place in

this horrifyingly polarized debate, because it is the Turkish perspective that

is the truthful one, but prejudice and political correctness, along with other

reasons, have allowed Armenian claims to overpower genuine history. Thus, in

order to come across as objective, real scholars are compelled to find fault

with the Turkish presentation. Not that there may not be faults with the way

some Turks approach the matter, but we can see Dr. Dyer did not truly make the

case for "Turkish 'Falsifiers'" in his 1976 essay (featured on TAT),

much as he was obligated to make it appear so in his title. (Similarly, Dr.

Lewy was also compelled to be overly tough on Turks, in his book. Ironically,

such preventative measures are for naught, since no matter how far real

scholars bend over backwards for Armenians, if they show the slightest iota of

fairness, they will automatically come under attack for being

"deniers," or as "agents of the Turkish government" —

and not just by unscrupulous Armenian extremists and their hypocritical

genocide scholar allies, but even lazy-thinking "neutrals," such as Scott Jaschik, a supposed

representative of "Higher Education.")

Little did I know at the time that Dr. Dyer heavily got into Ottoman history

during the 1970s. He actually consulted Turkish sources, as a true scholar

would be obligated to do, if the idea is to write Turkish history. (Unlike

false scholars such as Richard Hovannisian, consigned only to showcase sources

hostile to Turks, in the pursuit of a propagandistic agenda; note how

Hovannisian embarrassed himself on this shortcoming, when he went up against a real scholar

in 1978.)

The article below is from 1973, and while not genocide-related (except in an

indirect way: we can see the situation was desperate. Could the key people

involved logically afford to conduct a "genocide," when there were

so many pressing issues to attend to?), is deserving of a wider audience, and

to remind readers of the caliber of Gwynne Dyer's ace scholarship. Too bad

that as soon as Dyer brushed against genocide happenings, he evidently lost

his interest in Ottoman history. He probably figured the Armenians are a

dangerous people to get mixed up with, and who could blame him. (At least he

made one mini-comeback in late

2005.)

(What a coincidence. This page went up today, and I just learned that Dr. Dyer

has touched on the genocide once again, mere days ago. For the record, as he

wrote in The Record, Dr. Dyer is a genocide believer: "It was

certainly a genocide, but it was not premeditated, nor was it systematic."

He explains that as a young student, he had translated the handwritten diary

of a Turkish soldier whose unit was ordered in 1915 "to march east to

deal with a Russian invasion and an Armenian rebellion," and in the diary

the soldier had written "we really massacred them." If the soldier

was referring to innocent villagers, then that is the most solid evidence for

genocidal activity I have ever come across; very similar to what this American

soldier had written in a

letter, regarding 17,000 Filipino villagers. Then again, perhaps the Turkish

soldier was referring to their victory against those bearing arms against the

Ottoman army, as when a soldier could say after a victory, "we really

slaughtered them." Perhaps the rest of the diary provides further clues.

Regardless, perhaps Dr. Dyer relied on this diary entry as what he has termed

here, "this explains much," and has concluded that slaughter was a

matter of course by the Ottoman army for the non-"deported," and as

for the "deported," Dr. Dyer tells us, "huge numbers were

murdered along the way." I wish Dr. Dyer could have written a book with

the evidence for these statements; the bulk of the Armenians who lost their

lives died of non-murderous reasons, as famine and disease. The French

newspaper Le Figaro, not known for its Turk-friendliness, estimated the

numbers who had died from the marching process, and came up with 15,000 for deaths from all causes

— not just murder. 15,000 is not a small number, but it is only 1% of the

1.5 million Armenian propaganda tells us, a number that Dr. Dyer disturbingly

tells us is a possibility, as well.)

(Thanks to Hector.)

|

|

|

| The

origins of the 'Nationalist' group of officers in Turkey 1908-18 |

From the Journal of Contemporary History, Vol. 8, No. 4. (Oct., 1973), pp. 121-164.

The origins of the 'Nationalist' group of officers in Turkey 1908-18

Gwynne Dyer

The nationalist movement in Anatolia in the years 1919-23 was created, sustained, and led

by young staff officers of the Ottoman Army belonging to the same generation and group as

that which had carried out the original 1908 Revolution from Salonika against the despotic

and traditionalist regime of Abdülhamid. Under the brilliant leadership of Mustafa Kemal

Pasha it succeeded in assuming the mantle and some of the genuine characteristics of a

popular movement, but it owed its success to the disciplined organization of the Army. No

doubt there would in any case have been popular disturbances and even isolated instances

of mutiny within the Army in the face of Entente occupation of Turkish territory and the

Greek invasion of western Anatolia in 1919, and again against the Entente-imposed Treaty

of Sèvres in 1920 which for practical purposes put an end to Turkish independence; some

incidents of this sort occurred spontaneously, but such outbreaks had no hope of success.

The coordinated and unanimous withdrawal of obedience from the collaborationist Istanbul

government by all Turkish Army units in eastern and central Anatolia in the summer of

1919, and the smooth transfer of that obedience to Mustafa Kemal Pasha with an unbroken

chain of command; the assumption of control over the civil administration in Anatolia by

the Army wherever it did not get cooperation from the Istanbul appointees; the cautious

husbanding of material and diplomatic resources and the gradual remobilization of an army

capable of expelling the invaders; the suppression of internal revolts and the bringing

under regular Army discipline and command of the erratic and ineffective guerrilla forces

which had sprung up to oppose the Greeks in western Anatolia—these were the foundations

of Turkish victory in the War of Independence.

These accomplishments were the work—with the willing cooperation of the bulk of the

Army, to be sure—of a handful of senior Turkish officers. Mustafa Kemal Pasha was the

driving force and the overall head of the enterprise, with Rauf Bey (a naval officer) as

his chief political assistant. Kazim Karabekir Pasha commanded the Eastern Front against

the Armenians until its liquidation at the end of 1920, and by his influence in the area

guaranteed the loyalty of eastern Anatolia to the Nationalists throughout the war. Ali

Fuad Pasha was commander of the crucial Western Front against the Greeks and then the

first Nationalist ambassador to Moscow. Ismet Bey was the Chief of the General Staff at

Ankara and then Ali Fuad's successor on the Western Front. Refet Bey commanded the

Southern Front against the French in Cilicia, and was Kemal's chief agent in suppressing

internal revolts and in reducing the anarchic guerrilla bands to submission.

|

|

The emergence of these names at the head of the Anatolian movement was no

coincidence. There had existed in the Ottoman Army since 1909 a loose alliance among

certain officers who, though nationalist in conviction and all connected with the

revolutionary Committee of Union and Progress (CUP) in the early days, had fallen

out of sympathy with some of the more unsavoury ways of dealing with opposition

which the Society had the habit of using, with the erratic and authoritarian

behaviour of the Society when in power, and with the continual involvement of the

Army in political affairs to the detriment equally of Army discipline and training

and of political stability. Most prominent among these dissident officers were

Brigadier Mustafa Kemal Pasha [Atatürk], 37, Brigadier Ali Fuad Pasha [Cebesoy],

36, (naval) Senior Captain Rauf Bey [Orbay], 39, Brigadier Kazim Karabekir Pasha,

36, Colonel Ismet Bey [Inonü], 34, and Colonel Refet Bey [Bele], 37. Another early

ally of Kemal's who should be mentioned, though no longer in the Army after 1913,

was Ali Fethi Bey [Okyar], 38. (Ranks and ages as of end of 1918. The brackets

denote surnames assumed in accordance with the law of 2 July 1934.)

|

|

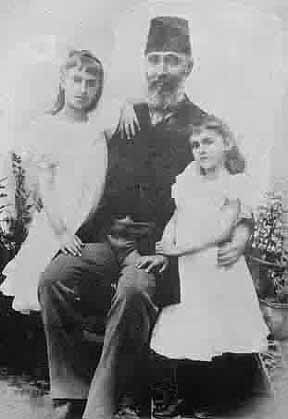

Dr. Gwynne

Dyer, in later years |

Their quarrel with the CUP was over means not

ends, and though most of these officers ceased to be active in the affairs of the

CUP by about 1910-11, and with two exceptions stayed out of politics from then until

the end of the first world war, several of them retained close if sometimes stormy

personal relations with the factions of interventionist officers whose leading

figures throughout this period were Enver and Cemal Pashas. The non-interventionist

group generally opposed Ottoman entry into the war on the side of the Central

Powers, but presented with a fait accompli they all fought loyally, and

indeed were among the most successful Ottoman commanders during the war. None of the

members of this military 'loyal opposition', except Kemal himself at the end of the

war, ever contemplated any attempt to overthrow Enver. Like the group opposed to

Enver in the CUP and the Cabinet itself, led by Talat Pasha (Prime Minister

1917-18), they dared not risk the danger of taking on Enver's large following in the

Society and the Army while the Empire was under external attack. Then suddenly, in

October 1918, the war lost, the CUP withdrew from power totally discredited, and

only a few weeks later its leading members fled the country. The field was clear,

and instinctively this group of 'Nationalist' officers (the title is conferred

retrospectively) foregathered in Istanbul to seek some way of rescuing the Empire

from the desperate situation in which Enver had left it.

THE COHERENCE AND EFFECTIVENESS of this small group of determined officers in the

midst of the political chaos and indecision of post-armistice Istanbul was the

result of a decade of association and common effort. Kemal and Ali Fethi first met

and became close friends at the Military Training School in Monastir in 1895-98; it

was from him that Kemal first learned of 'something called politics'. At the

Military Academy and the Staff College in Istanbul in 1899-1905 Icema1 associated

closely with Ali Fuad and Kazim, who were distant relatives and had been close

friends since childhood. Ali Fethi, who was in a more senior class, also met these

classmates of Kemal's through him. In Istanbul Ali Fuad was Kemal's closest friend,

and his father, Ismail Fazil, a senior army officer of some note, virtually adopted

the young Kemal. In 1905 Ali Fuad and Mustafa Icema1 were arrested together for

plotting against the regime and, after some months imprisonment, exiled to the 5th

Army at Damascus. About a year later Ali Fuad was appointed back to Salonika, where

the CUP was taking root among the young army officers and the revolution was in

preparation, but Kemal was able to visit there only briefly and in secret before

1908. As a result of his absence from Salonika at a crucial stage in the growth of

the CUP, Kemal took a lesser role in the 1908 Revolution than Ali Fethi, Ali Fuad,

or Kazim; his subsequent open criticism of the Army's continuing involvement in

politics and in particular of Enver, whose posturing as the hero of the Revolution

he abhorred, led to his being sent on a special mission to Libya to get him out of

the way. But he was back in Salonika in time to take part in the suppression of the

counter-revolution of 13 April 1909—the 31 March Event (old style)—and it was

then that a 'Nationalist' group first took shape.

|

| |

Kemal was Chief of Staff of the 11th Reserve Division commanded by Huseyin Husnu Pasha in

Salonika when the counter-revolution broke out in Istanbul. The senior commanders in

Salonika hesitated to commit the Army officially to the suppression of the revolt in the

first few days, when the news arriving from Istanbul was confused and contradictory, and

so Kemal's proposal to send to the capital an ad hoc force made up of volunteers

from both the regular Army and the reserve was instantly accepted. It had the right

popular flavour, and kept the skirts of more senior officers clear. The force was named

the Hareket Ordusu (Action Army) as he suggested, and he and Hüseyin Hüsnü Pasha were

made its chief of staff and commander respectively. The Hareket Ordusu set out for

Istanbul on 16 April, and Kemal remained effectively its moving spirit until it arrived

outside the walls of Istanbul, to be joined there as he had proposed by another contingent

of volunteers from Edirne.

By that time, however, it had become clear that the revolt was an outbreak confined to the

capital. The CUP had regathered its forces and its leading Army members like Enver, Ali

Fethi and Hafiz Hakki came racing back from the capitals of Europe, where they had been

sent as attach& after the 1908 Revolution, to take up the key positions in the Hareket

Ordusu. The Army's senior officers had recovered their nerve also, and on 22 April the

Third Army (Salonika) commander Mahmud Shevket Pasha assumed command of the force outside

Istanbul. Kemal was relegated to the background in the final suppression of the revolt

amidst scattered street fighting in the next few days.[1]

After the Army had entered the city and put down the revolt, Icema1 for the first time met

Hüssein Rauf Bey, a young naval officer prominent in the CUP who was attached to the Army

for liaison duties. The two officers agreed that the counter-revolution was the direct

consequence of the evil effects of soldiers participating in politics, a conclusion

confirmed by the special court of inquiry into the causes of the uprising, of which Rauf

was a member. Kemal and Rauf found other young officers in Istanbul at this time in whom

the events of the past year had created strong opinions about the necessity of separating

politics from the Army. There was Kazim Karabekir, Kemal's classmate at the Staff College

and a friend of Rauf's since before the Revolution. He had participated in the founding of

the CUP centres in Monastir and Edirne and was now Chief of St& of the Hareket

Ordusu's Edirne contingent. There was Refet Bey, a young gendarmerie officer at Kemal's

headquarters who had worked with Fethi and Keinal before the Revolution; and Ismet Bey, a

youthful staff officer whom Fethi and Refet recruited to the CUP and who had later

cooperated with Kizim in founding the Society's organization in Edirne; there was Rauf's

friend since childhood, Selgnattin Adil Bey.

Together with Dr Nazim, a former exile and a major power behind the scenes in the CUP,

Tevfik Rüshtü [Aras], and some others, Kemal, Kazim, Ali Fuad, [2] Ismet, Refet and Selahattin Adil now briefly became virtually an

opposition faction within the CUP. They argued that it must give up its old ways of

intrigue and assassination now that it had the responsibility of power, and that, though

the Army's support continued to be vital to the Revolution, a clear line must be drawn

between those active in politics and those on active service in the Army. Together the

young staff officers signed a note condemning the intrusion of politics into the Army, and

Ismet Bey presented it to the army commander Mahhud Shevket Pasha. He accepted it, and

even instructed Ismet to write an order to the forces under his command laying down this

principle. Furthermore he communicated the contents of the note to the other Ottoman Army

commanders for their consideration, but it had no discernible effect in either his own

army or the others.

Some four months later, at the annual congress of the CUP in Salonika in September 1909,

Kemal forcefully presented his view that the Army and the Society must be separated for

the good of both. He submitted a resolution proposing that army officers must decide

whether to remain in the CUP and resign from the Army, or stay in the Army and resign from

the Society. Kemal was fortunate in being one of the men selected to chair the sittings,

and he had the wholehearted support of Tevfik Rüshtü, who was elected general secretary

of the congress. He succeeded in gaining the conditional support of a majority of those

present for his view, and it was decided to send a commission to the Second Army at Edirne

(less well represented at the congress than the Third (Salonika) Army) to sound out

opinion among the officers there. Refet Bey was chosen to head this commission; Ismet and

Kazim marshalled the support of their fellow officers in Edirne behind Kemal, and the

commission returned in a few days to report that the Second Army supported Kemal's thesis.

His motion was passed by a large majority.

|

|

Although many officers did then make the choice between Army and Society, the most

influential young officers like Enver and Cemal did not. Moreover the majority of

the Society's leaders, now aware that the Revolution did not necessarily have the

support of the masses, were unwilling to break their connexion with the Army. The

resolution was never put into effect, and the CUP lost its one real chance to

transform itself from a revolutionary cabal into a genuine political party. Indeed,

Kemal was lucky to escape the attempts of the assassins who were now turned loose on

him because of his dangerous views. Neither his ambitions and convictions, nor his

contempt for the strutting figure of Enver, diminished, but he and his friends now

saw their safest course of action as immersion in their military duties.

Rauf Bey later noted: 'Having seen [the consequences of soldiers becoming involved

in politics], we firmly resolved that from that day forward .. . our most important

and sacred duty to the fatherland and people would be to use our influence and

authority to prevent soldiers from mixing in politics. This course of action of ours—just

as had been the case with Mustafa Kemal Bey previously—was ill-received. Right up

to... the end of the CUP'S reign [in 1918] we remained under suspicion, and so

encountered difficulties in carrying out our duties and were sometimes condemned to

idleness.'[3]

Referring decades later, when his own power was secure, to this same parting of the

ways between the 'Nationalists' and the officers who then stayed in the CUP, Kemal

Atatürk explained why it happened and why it had brought disaster in its wake.

'Those at the head of the CUP revolution who later entered the government were our

close friends. In the first phase we were all together. After the Revolution we came

out against them, arguing that the Army should not mix with politics-more precisely

that we should not mix in politics as army officers. We quarrelled with them over

this idea Ad parted company, unable to agree. We withdrew from politics and carried

out our duties in the Army. Thenceforward be had no direct connexion with the

government of the country. We passed through many stages and &any experiences,

we made careers for ourselves and [gradually acquired our present abilities].

Whereas our friends who had made the Revolution with us and were on the same level

as ourselves passed to the head of the country at that time. . .We are not the raw

men we were then; we are different now. But they tried to govern the country and

ward off all the dangers which threatened it . . . with no more experience than we

ourselves had then. How could they have been expected to succeed?’ [4]

LIKE ENVER, BOTH KEMAL AND FETHI SERVED in Libya in 1911-12 in the guerrilla war

which the Ottomans launched there after the Italian seizure (Rauf was in charge of

running guns and supplies into Libya). Relations between Kemal and Enver became

severely strained, but an open break was narrowly avoided. While they were absent

overseas, the CUP engineered an election to pack the Chamber of Deputies with its

own supporters and so quell the rising opposition in the country to its policies.

Following this 'Big Stick' election, the CUP was forced out of power in the summer

of 1912 by the revolt of a group of 'Saviour Officers' in Istanbul and Macedonia.

Besides the resignation of the Government, these officers successfully demanded what

Kemal had failed to achieve in 1909, the imposition of an oath upon army officers

not to meddle in politics. But later in the year the Balkan states, for once united,

attacked Turkey and in scarcely a month seized the entire remaining territory of the

Empire in the Balkans. When the officers hastily recalled from Libya reached

Istanbul in November and December 1912, they found the Bulgarian Army only thirty

miles west of the city facing the Chatalja lines, and the new Government seemingly

about to agree to a peace which would cede not only Macedonia but all of Thrace to

the enemy, including the old Ottoman capital of Edirne which was still withstanding

a Bulgarian siege.

A CUP coup organized by Talat, the most influential figure in the inner circle of

the Society, overthrew the Government on 23 January 1913 and installed a new cabinet

strongly influenced by the CUP. In organizing the coup Talat had to rely primarily

upon the ambitious young army officer members of the CUP whom both their own

superiors and the civilian leadership of the CUP had hitherto striven to keep in the

background and away from the levers of power. Enver led the assault on the Cabinet

Room in which the War Minister Nazim Pasha was killed, and became the hero of the

coup just as he had earlier been the hero of the Revolution. Committed to continuing

the war, the new Government felt the need for an immediate military success to

consolidate its shaky political position. The Bulgarians anticipated the Turks by

announcing that the armistice in effect since 3 December would expire on 3 February.

The Government under CUP pressure overrode the commander-in-chief Ahmed Izzet Pasha

[Furgach] and insisted on an offensive being launched at once. There ensued a clash

between Enver on the one hand and Kemal and Fethi on the other which was to be the

foundation of a close and long-lasting political cooperation between the latter two.

|

Mustafa Kemal (third from left, center) and Ahmed Izzet Pasha

along with other officers pose in Aleppo, Feb. 2, 1917 |

|

|

Rauf Orbay (1936 oil painting, J.C. Mertan)

commanded the Hamidiye ("Ghost Ship")

during the Balkan War, breaking through a

Greek blockade of the Dardanelles, and by

hitting the Bulgarians and Montenegrins |

At this time Fethi and Kemal were respectively Chief of Staff and

Operations Officer of the force under General Fahri Pasha which was holding the neck of

the Gallipoli peninsula at Bolayir against the Bulgars. (They were in close contact with

Rauf Bey at the naval base opposite at Nara harbour, until Rauf took his cruiser Hamidiye

on its famous raiding cruise.) Fethi was a much more important figure in the inner

councils of the CUP than any of the Nationalist officers and had never given strong

support to the idea that soldiers must stay out of politics—almost certainly he had no

part in the note submitted by the Nationalists in 1909, and he had been elected the deputy

from Monastir in the 1912 elections despite the fact that he was on active service in the

Army. Remal too, due to his great ambition and conviction of his own worth, and the

powerful sense of rivalry with Enver which had been one of his main motives for action in

1908-09, was able to abstain from politics only for short periods despite his theoretical

beliefs—his patience was easily exhausted. Fethi had not fully accepted Kemal's

criticisms and warnings about Enver in 1908, but by 1912 Enver's rapid march towards power

had awakened the same fears in him as well. Both Fethi and Kemal had advised against the

coup at least until an attempt had been made to force the Government out by constitutional

means; indeed Fethi had managed to get this view accepted at the first of the Istanbul

meetings in which the CUP considered the coup, only to have the decision reversed in a

second meeting after he had returned to Gallipoli and Enver had reached Istanbul. On the

morrow of the coup their worst fears seemed about to be realized: Enver now looked

unstoppable.

They had scant resources with which to counter him. Though they knew quite well that the

Army was in no shape to undertake an offensive, they knew also that political

considerations demanded one. So, quite contrary to military practice, on 4 February 1913,

they submitted a joint report to the War Minister and the Deputy C-in-C, bypassing their

corps commander. In the report they condemned the coup, but stated that an offensive had

to be launched immediately from both the Chatalja lines and the Gallipoli peninsula, to

relieve Edirne before it fell and the Bulgarian army encircling it was freed to join the

main Bulgarian army before Istanbul. If the offensive succeeded, they would at least share

the credit with Enver for recommending it. If it failed, the responsibility would rest

with those in the High Command who had done the planning.

As it turned out they were not to escape some of the blame for failure, for Enver chose to

make his offensive wholly at Gallipoli. He secured the consent of the reluctant C-in-C for

an entire army corps to be landed from the sea at Sharkoy above the base of the Gallipoli

peninsula at the same time that Fahri's force at Bolayir launched an all-out attack, the

object being to catch the Bulgars between two fires. Enver himself was Chief of Staff of

the 10th Army Corps which was to carry out the landing, with responsibility for

coordinating the actions of the two forces. Orders for the landing were given on 4

February, to be carried out four days later. Though there were no Bulgars at

Sharkoy on 8 February, the landing attempt was an appalling shambles, and after thirty-six

hours was abandoned. Meanwhile the force at Bolayir, which was not informed of this, made

its frontal attack unsupported and was smashed with the loss of nearly half its men.

|

|

Enver Pasha |

A bitter dispute broke out between Fethi and Kemal on the one hand,

and Enver on the other, over the responsibility for this debacle, conducted both openly

and by means of unsigned pamphlets. Fethi and Kemal's campaign against Enver rapidly made

progress and came near to splitting the officer corps into pro- and anti-Enver factions;

the new Prime Minister Mahrnud Shevket Pasha went to Gallipoli on 20 February in an

unsuccessful effort to settle the dispute. Shevket saw more justice in the Fethi-Kemal

side of the argument, but his attempt to defuse the dispute by bringing the 10th Army

Corps, of which Enver was Chief of Staff and de facto commander, back to Istanbul

quickly backfired. When the threat of an opposition counter-coup led by Prince Sabahattin

frightened Shevket in early March, the forces he had to depend on for the preparation of

possible military countermeasures in the capital were commanded by Enver and by Cemal

Pasha, the military governor of the city and another army officer with a personal

following and an urge for political power. Though the Fethi-Kemal campaign against Enver

continued even past the end of hostilities, the latter's position, already greatly

strengthened by his command of the force safeguarding the Government in Istanbul, was made

virtually unshakable by his ostensibly heroic role in the recovery of Edirne at the end of

the Second Balkan War on 23 July 1913. Furthermore, the assassination of Mahmud Shevket on

11 June had given the CUP the excuse to abolish in effect all political opposition. More

than ever before, reckless young army officers controlled the CUP and the Empire, with

Enver, the most powerful, the most reckless of all.

|

|

|

|

Fethi Bey (Ali Fethi Okyar) |

Shortly after the Sharkoy affair Talat brought

Fethi to Istanbul on 16 March 1913, and had him appointed to the Central Committee

and the General Secretariat of the CUP. His motive almost certainly was to seek a

counter-balance to the monster he had created by allowing Enver to lead the assault

on the Sublime Porte, and to recover a measure of control over affairs for the

civilian wing of the CUP, by supporting another young officer with a following of

sorts. Fethi now resigned from the Army, while Kemal remained with General Fahri's

force, now as Chief of St&, until October 1913. But at the end of the war in

August 1913 he took leave and went to stay with Fethi in Istanbul, where they sought

ways of exploiting Fethi's new position. It was a powerful one, but Fethi tried to

do too much.

At the 1913 Congress of the CUP Ali Fethi in cooperation with Talat announced, not

for the first time, that the CUP was to be converted from a semi-secret society into

a political party. The amendments made to the CUP constitution at the congress had

the aim of shifting the centre of decision-making out of the secret Central

Committee and in the direction of the general membership of the hitherto subordinate

Parliamentary Party of Union and Progress; the change was necessitated by the

growing ascendancy of Enver and the army side of the CUP generally in the Central

Committee and the inner circles of the Society. Though Talat secured a superficial

success, it was of no use against the fact that the balance of power within the CUP

had swung strongly in favour of the young staff officers after the 1913 coup, and

within a year both Enver and Cemal Pashas (as they became) had forced their way into

the leading positions in both the CUP and the Cabinet.

Had Fethi confined himself to cooperating with Talat in this enterprise, his

position would probably have remained secure. But in addition he continued his

campaign of accusations against Enver and, despite Kemal's warning but probably with

Talat's private encouragement, he tried to cut the ground from beneath Enver's feet

by depriving him of the support of bis 'silahshorlar'. These 'warriors' were Enver's

personal retinue of young bravoes, mostly junior army officers who had distinguished

themselves by assassination and terrorism in the service of the CUP in the early

days and who had subsequently hitched themselves to Enver's star : they were shortly

to bring him to the War Ministry despite Talh's opposition. Fethi's plan was the

simple one of seeking to stop their salaries and dismiss them from the CUP'S

service, but here he overreached himself. The addition of this violent element to

their opponents made Fethi and Kemal's situation hopeless, and to save Fethi's life

from the assassins Talat in October 1913 warned him to resign his posts and go to

Sofia as ambassador. When Fethi and Kemal sought counsel on this warning from Cemal

Bey, the Minister of Marine and Enver's leading rival, whom they both trusted, he

endorsed Talat's advice and warned Kemal that he had better go with Fethi to Sofia

as military attachi. They took his advice and went.[5]

NONE OF THE NATIONALIST OFFICERS except Fethi and Kemal had been involved in this

political operation, and this was a pattern to be repeated in the future. [6] Even before he left the Army Fethi was more

politician than soldier, and Kemal, burning with ambition and resentment at the

meteoric rise of his old rival Enver, was prepared to engage in political intrigue

to rescue the country from incompetence and to bring himself to the prominent

position he was convinced his talents deserved. The remainder of the group which had

gathered around Icema1 in 1909 were more sincere in their detestation of political

intrigue in the Army, and in any case (with the exception of Rauf, an Anglophile

with an unshakable conviction of the necessity of the separation of the military

from politics) were too junior and too distant from Istanbul during most of the next

five years to be tempted to meddle in politics. The instinctive cohesion of the

group survived, and rose quickly to the surface in 1918 ,but despite the appalling

mismanagement of the war by Enver Pasha there was little joint action or planning by

these officers in the war years 1914-18.

The Nationalist officers were not of course a formal group at all, nor at any time

before 1919 were they sufficiently distinct, prominent and permanent as a faction to

warrant their being given, or giving themselves, a name such as that imposed on them

here for convenience. They were a group bound first by such ties as would ordinarily

bind officers of the same age who had for the most part gone through the Military

Academy and Staff College together, and later fought in the same campaigns side by

side, but cemented more firmly by their shared experience of conspiracy, revolution,

and the suppression of counter-revolution in the dramatic years 1907-09. What made

this particular group of officers from that much larger number who also shared this

background a special and self-conscious group with a political potential, was their

awareness of the officer corps' responsibility as Turkey's leading elite, and their

conviction, first formed in 1909 and greatly strengthened by the catastrophic

mismanagement of the first world war, that this elite was betraying its

responsibility. An additional and crucial factor was the enormously powerful

personality of Mustafa Kemal, who provided a nucleus about which the group could

form. The final necessary element which ensured the survival of the group's

identity, however dormant, over the long years between the first flush of enthusiasm

in 1909 and the first opportunity for common action in late 1918,was the dominance

of Enver Pasha and his extremist allies over the affairs of the Army and the Empire

as a focus for their dissatisfaction.

Except for Kemal these officers were not gifted with any extraordinary insight into

international affairs or even civil-military relations. Indeed, the ideal to which

they nominally gave their loyalty—the strict separation of the Army from politics—would

have to be abandoned if they were ever to take any action to right what they saw as

being wrong with the existing situation, and it was dropped without a qualm in 1919.

Asked recently if the Nationalists' use of the Army to create a rival government in

Anatolia in 1919, and their defiance of the legitimate Istanbul government which was

collaborating with the Entente, was not a betrayal of this ideal, Ismet Inonu

replied frankly: 'The [War of Independence] was basically a revolution by the Army.

That is as plain as day. The way things were, what else should we have done? The

enemy had invaded the country; we had to liberate ourselves. We had the Army, and

the Army had to fight.'[7]

|

| |

In any case, the destructive influence of politics on the Army was no longer a live issue

after 1914, for once he came to the War Ministry Enver pulled the ladder up behind him. In

a single industrious year he not only reorganized the structure of the Army on the

contemporary European pattern and cleared out all the deadwood by a mass retirement of

virtually all officers who had reached field rank before the Revolution; he eradicated

politics from the Army root and branch. Even his own 'warriors' were not spared; they were

found jobs in the new Special Organization or in various CUP posts, but they had to leave

the Army.[8] But although Enver removed politics from

the Army he did not remove the Army, under his direction, from politics; he was merely

ensuring that no rival voice could speak for it. The Army constituted the power base which

let him play the dominating role in the Empire's entry into and policies during the first

world war.

One grievance against Enver and generally against the CUP was thus quickly replaced by

another. It required no special insight to see that Enver's impulsiveness in the direction

of Ottoman strategy, his subservience to German strategic needs in the direction of

Ottoman forces, the arbitrary violence which the CUP Government sporadically employed

against political opponents and minority groups, and the flagrant and large-scale

corruption of many of the lesser members of the government, were leading the Empire to

ruin. Even though the Nationalist officers had no such thing as an alternative programme,

the blindingly obvious contrast between Enver's military policies and the real

requirements of the Empire's situation, and the bitter resentment almost all of them felt

at the dominating positions given to German officers in the Ottoman Army, provided them

throughout the war with a permanent motive to disapprove of Enver's regime and to discuss

their views with others of like mind.

|

|

Mustafa Kemal

Atatürk |

THE GROUP WHO HAD ASSOCIATED THEMSELVES with Kemal in

1909 were in close contact with each other during the war owing to the circumstance of

postings. Just as important, from the middle of the war on most of them came by chance

into contact with the man who was to be Turkey's Prime Minister at the time of the

armistice and won his confidence. This man was General Ahmed Izzet Pasha, a successful

soldier of the old school who had reluctantly let himself be made the Minister of War

after the assassination of Nazim Pasha in January 1913, only to be pushed out of office

again the next year by Enver. Some of Kemal's associates he already knew well—Ismet and

Rauf had accompanied him to the Yemen in 1910 to suppress the revolt there, the former at

Izzet's specific request—and most of the others including Kemal himself he served with

during 1916-18. A man without a party, when he was called upon to form a successor

government to the CUP and make peace in October 1918, it was to the members of this group

of officers that he turned for support, thus giving them a priceless opportunity.

From his semi-exile in Sofia Kemal had become partially reconciled to Enver upon seeing

the excellent work in Army reform which he set in progress as Minister of War in 1914, and

even made known to the CUP leadership through a well-connected friend his willingness to

serve under Enver as Chief of the General Staff—an idea which Enver rejected out of

hand. However, on the outbreak of war Kemal realized that the Government intended to join

Germany, and urgently sought through both official and private channels to persuade the

Government to remain neutral and await the development of events, fearing all too

accurately that it would be a long war and that the Germans were by no means certain of

victory.[9] When war came anyway, he sought to return

to Turkey and take his part in it, but for some months Enver insisted that he remain in

Sofia. Finally on 20 January 1915 Enver appointed Kenal to command a reserve division

forming near Gallipoli.[10] In the next ten months

his brilliant work in the Peninsula, where he twice saved the Turks from irremediable

defeat, was the making of his reputation within the Army. Enver used the military

censorship to ensure that Kemal's reputation did not grow correspondingly in civilian

circles (though in the Anafarta battles Kemal commanded a force of eleven divisions, the

largest under a single Turkish commander in the entire war), and contrived to delay his

promotion to General and Pasha for more than a year. After Gallipoli however there was no

longer any possibility of Kemal's being left to languish in exile or in some harmless

administrative post, whatever doubts Enver might have about his trustworthiness.[11]

In the first years of the war Kemal eschewed political intrigue entirely. His attitude at

the beginning is summed up in his response to a questioner who asked him why Turkey had

entered the war: 'Never mind that now; it's done. Now we must do our duty.'[12] As time went on and Turkey's military situation became more grave, he

could not refrain from uttering protests and warnings, but now he had the position and

authority—Colonel and Corps Commander in 1915, General, Pasha, and Army Commander by

1916—which enabled him to do so openly and receive a hearing. From the end of 1915 to

the end of the war he issued a steady stream of messages and memoranda to the High

Command, always inveighing against the erratic and irrational conduct of Ottoman strategy

and the undue influence of German officers in the Army.[13]

Sheer frustration at his inability to get his views accepted was responsible for the fact

that three times before mid-1918 he offered his resignation from important commands (twice

having it accepted) and three times refused similar appointments. But not until late 1917

did he again engage in any political activity.

|

|

|

|

Ali Fuad |

On 16 January 1916, shortly after resigning his

command at Gallipoli, Kemal was appointed to command the 16th Army Corps at Edirne.

This was part of the 2nd Army then being formed from units withdrawn from the

Gallipoli peninsula, and a short time later Ahmed Izzet Pasha, at last given another

job by Enver, was brought to command it. Within a few weeks Enver decided to send

this army to counterattack the Russian flank and drive them out of eastern Anatolia;

Kemal arrived at Diyarbekir in the East on 13 March. Here he had no such spectacular

successes as at Gallipoli, though winning some limited victories at Mush and Bitlis

in the Turkish counter-offensive which began after the bulk of the 2nd Army troops

had reached the area in the late summer. He and Izzet got to know each other well in

the year that they fought together on the Eastern Front; equally important, Ismet,

Ali Fuad, and Kazim Karabekir, whom Kemal had not often seen since 1909, took up

duties in the 2nd Army in the course of that year and renewed their old links with

him and each other.

Ismet and Kazim had served together in Istanbul on the General Staff in 1913-14 as

the senior Turkish officers in the Operations and Intelligence sections respectively

and had established close relations—indeed they had taken a month's leave together

in the summer of 1914 and toured Western Europe. Kazim had been sent away from the

General Staff in 1914 because of his opposition to German influence in the Army and

to Turkish entry into the war, and after various peregrinations had ended up

commanding a corps in Iraq in the battles around Kut-el-Amara. Ismet's views had

been the same, but because of Enver's regard for him the Germans did not succeed in

procuring his removal from the General Staff until early 1916, when Ismet was

appointed Chief of Staff to Izzet Pasha, his former commander from the Yemen, in the

newly formed 2nd Army.

Ali Fuad was now commanding a division in the 2nd Army, and Kemal saw him for the

first time in five years when in August 1916 he rescued Fuad's force from a

difficult position. There was an emotional reunion, but these two old friends did

not have much opportunity to see each other at this time. The situation was

different with Ismet, whom Kemal had not known very well previously and had never

before worked with in any official capacity. When Izzet Pasha left for Istanbul on

leave in November 1916, Kemal began to deputize for him as 2nd Army commander, and

Ismet became effectively Kemal's Chief of Staff. Two months later Ismet was given

command of the 4th Army Corps under the 2nd Army. The close relationship of the two

men continued for a year, and their attitude towards the disaster rapidly overtaking

the Empire developed in constant mutual consultation.

On 2 March 1917 Izzet Pasha was appointed to overall command of both Ottoman armies

in eastern Anatolia, and thereupon Kemal was made substantive commander of the 2nd

Army. During the spring yet another of Kemal's old comrades and future collaborators

joined him in the 2nd Army when Kazim Karabekir arrived to take over the 2nd Army

Corps, and subsequently to act as Kemal's second-in-command in the 2nd Army. The

dormant links which were revived and the new ones which were established among these

four men, and between them and Izzet Pasha, were to bear fruit in little more than a

year's time.[14]

On I May 1917 Ismet was appointed to command the 20th Army Corps on the left flank

of the Gaza front in Palestine, but within a few months he was replaced there by Ali

Fuad, also transferred from the now quiet Caucasus. After a short leave in Istanbul

Ismet was appointed to command the 3rd Army Corps in the new 7th Army, then forming

around Aleppo in Syria. When he reached Aleppo he found that once again his

immediate superior was Mustafa Kemal, now transferred from the Caucasus to command

this new 7th Army. Kemal and (indirectly) Ismet became involved in a bitter dispute

with Enver in the next few months over the latter's grandiose project for the

recapture of Baghdad by a 'Yildirim Armies Group' of which the 7th Army was to form

part. Kemal succeeded in dissuading Enver from this project with the help of Cemal

Pasha and the Germans, only to have Enver decide to use the force instead for a

further attempt to invade Egypt. In disgust Kemal decided to resign, but before he

did so he and Ismet prepared their renowned report on the state of the Empire and

the measures necessary to rescue it from disaster. On 20 September 1917 they sent it

in cipher to Enver, the Deputy Commander-in-Chief (the Sultan being the nominal

C-in-C). Contrary to military discipline, they also sent a copy together with a

letter directly to the Prime Minister Talat Pasha.

It was not a report merely on the military situation; it dwelt on the desperate

state of the country's economy and administration and warned of the possibility of

the sudden collapse of the whole structure of the Empire if measures were not taken

at once to put things right. On the military side the report mercilessly analysed

the rapidly progressing deterioration of the Army and the precarious situation on

the fronts. It recommended the removal of all German officers from positions of

command and the adoption of a strictly defensive strategy aimed only at preserving

Ottoman territory and lives. Ottoman troops serving abroad should all be recalled,

and no further attempts should be made to serve the supposed broader strategic

interests of the alliance by wasteful and foredoomed offensives on the Ottoman

fronts. Only in this way would there be some hope of defending the Empire

successfully.

On 24 September Kemal followed this with a telegram to Enver containing an

ultimatum: either he must dismiss the German commander Falkenhayn from the Palestine

front and place all forces there under one army to be commanded by Kemal, or he must

accept Kemal's resignation. Enver's reply of 12 October was polite and conciliatory,

but gave no indication whatever that he intended to act on any of Kemal's proposals.

On receiving it Kemal instantly submitted his resignation and, without awaiting an

acknowledgement, appointed a deputy to command his army and withdrew. He rebuffed

Enver's attempts to persuade him to remain, refused an offer to reappoint him to his

former command of the 2nd Army in the East, and returned to Istanbul as, in his own

words, 'a rebellious general'.[15]

|

| |

|

|

Refet Pasha |

During this last war year the Nationalist officers were mostly

either on the Palestine front or in Istanbul, with Kemal as usual serving as the vital

link among them. A few weeks after his departure from Syria Ismet's 3rd Army Corps was

transferred to the Palestine front and took its place in the line next to Ali Fuad's 20th

Corps, and the two men served side by side through the next year in Palestine as the

military situation moved steadily towards collapse, until at the very end of the war they

came again under Kemal's command when he was reappointed commander of the 7th Army.

Besides Ali Fuad and Ismet, Refet was on the Palestine front as a corps commander; he had

been there since the outbreak of the war and had already played a distinguished role in

the Suez Canal attacks and in the battles around Gaza in early 1917. Kazim Karabekir

remained on the Caucasus front until the end of the war, out of contact with the rest for

the most part. The remainder of the Nationalist officers were in Istanbul and in

increasingly frequent contact with Ahrnet Izzet Pasha during this year.

After his resignation in October 1917 Kemal was not offered a command again until the last

few months of the war, which suited him very well, for he now launched himself into

political intrigue aimed at displacing Enver, if possible taking his place himself.

Benefiting from the loose rein which Enver as always allowed him, he obtained three months

leave and set about politicking. He saw a great deal of his close friend Rauf, now Chief

of the Naval Staff, and they discussed the country's difficulties at great length: but

Rauf was serious about the military not mixing in politics and refused to have anything to

do with Kemal's intrigues while he remained in office—indeed he made a practice of

delivering Kemal homilies on the subject. Kemal's main collaborator was Ali Fethi, now

back from Sofia and at the head of an opposition movement in favour of a separate peace

which was emerging among the parliamentary members of the CUP. For the next sixteen months

all Kemal's efforts were focused on obtaining the War Ministry for himself, at first in

order to conclude a separate peace, later in the hope of being able to deal more

effectively with the victorious Allies.

During their earlier period of close collaboration in 1913 Kemal had unquestionably been

subordinate to Fethi, who had then occupied a position of power in the CUP, whereas Kemal

had been a relatively junior officer with neither political nor military success to his

credit. To many in the CUP and the Army, and to the austere Enver in particular, his

constant open criticism of the actions of those in responsible positions had been merely

the reprehensible consequence of his great ambition, his arrogance, and his fondness for

drink. But now there could be no question, at least among his contemporaries in the

Society and the Army, of his genuine abilities, and his status and influence in this

circle were at least as great as Fethi's. He was still not very well known outside this

circle, as his leading role in the Gallipoli campaign had been deliberately played down by

Enver; but shortly after his return to Istanbul he took steps to remedy this. In a series

of interviews with Rushen Eshref [Unaydin], a writer for Zia Gokalp's Yeni Mecmua, he

described his own part in that campaign; the account Unaydin wrote, appearing fast in a

special issue of Yeni Mecmua to commemorate the third anniversary of the naval assaults on

the Dardanelles in March 1915, and subsequently as a separate pamphlet, helped to make him

known to the wider audience of educated Turks outside the Army.[16]

Meanwhile Fethi and Kemal sought a way to bring Enver down, and in November or early

December 1917an opportunity of sorts presented itself. Shortly after Talat Pasha had

become Prime Minister in a reconstructed Government in early 1917, a serious division had

begun to appear in the Cabinet between the supporters of Enver and Talat on the issues of

Army control over civil affairs (the whole country was under martial law) and the

desirability of trying for a separate peace. It was in essence a recrudescence of the old

split between the civilian and military wings of the CUP, with the addition of a

personality clash; by the spring of 1918 this division had become so deep that Talat was

to engage in at least one abortive scheme to remove Enver and his followers from the

Cabinet,[17] but at this time he was still trying to

preserve a common front. Enver's supporters, on the other hand, were already taking

precautions against such an eventuality. According to Kemal, Ismail Hakki Pasha, one of

Enver's closest associates at the War Ministry, approached him shortly after his arrival

in Istanbul and revealed to him in confidence that the Government's will to continue the

war was weakening; if it appeared likely that it was going to seek a separate peace it

would be necessary to overthrow it and install a military cabinet. Would Kemal accept a

position in that cabinet? Ismail Hakki added that he had under his personal control a

force of 10,000 men distributed around the capital and various places on the Anatolian

coast of the Marmara, its purpose known only to Enver and himself, which was being held in

readiness to carry out this coup if necessary.

While such a force did indeed exist,[18] it is

difficult to believe that Enver and Ismail Hakki would have tried to enlist Kemal's aid in

this way—they knew his attitude to the war and to themselves. The real source of Kemal

and Fethi's knowledge may well have been Ali [Chetinkaya], the commander of these secret

'assault battalions', who had known them both in Salonika in 1908 and had served with them

in Libya. In either case they seized on the existence of this force as a weapon to use

against Enver. Fethi went at once to see Talat and warned him of its existence, first

getting his word not to reveal the source of his knowledge. Talat was greatly alarmed at

first and consulted immediately with his close friends and members of the Central

Committee Mithat Shükrü [Bleda] and Kara Kemal Beys. But on further discussion they

found it difficult to believe that Enver would consider such an action, and Talat despite

his promise to Fethi decided to demand an explanation from the War Minister. Enver freely

admitted the existence of the force, but denied that it was directed against the Cabinet;

it was he said merely a precaution against another attempt at a coup such as that Yakub

Cemil had tried the previous year. Talat had to give the appearance of accepting this

assurance, [19] and did indeed conclude that Fethi's

revelation had had the purpose of creating suspicion and distrust of Enver in the Cabinet,

which would lead to his exit from it.

Talat's conclusion about Fethi and Kemal's motive was certainly correct. This was entirely

clear to Enver, but once again he did not take strong action; he contented himself with

giving a strong warning to Rauf to relay to Kemal that this was the last time he would

overlook his 'political intrigues'. 'There is no question,' he said, 'that Mustafa Kemal

Pasha is a person who can be of the greatest service to the country. And I will continue

to employ him in the positions he is entitled to. But I am certainly excused from

consenting to a continuation of these political enterprises.'

|

|

Rauf left Istanbul a few days later to serve as Ottoman military representative at

the Brest-Litovsk peace negotiations together with Izzet Pasha, now returned from

the Caucasian front. Calling at Berlin on the way he spoke to Kemal, who had

preceded him there by a few days in the company of the heir to the throne Vahideddin.

Kemal's alarm when Rauf told him that Enver knew what had passed between Fethi and

Talat is clear proof of his purpose in this affair. Rauf calmed him by telling him

of Enver's willingness to overlook the matter, but could not resist delivering a

lecture on the principle of non-interference by the military in political affairs on

which they had previously been in agreement. Kemal explained that he felt he had no

choice; Enver had offered to make him a deputy in the Chamber if he wished to enter

politics, but the deputies were powerless these days, so there was nothing to do but

continue as a soldier. Rauf was right about the intervention of soldiers in

politics, however; he now pinned all his hopes on the Crown Prince, who must before

long ascend the throne as the Sultan was very ill. Vahideddin was a different sort

of man from Mehmed Reshad; Kemal was doing his best to enlighten him on the true

situation in the country and things would be bound to improve when he became Sultan.[20]

Enver's behaviour on this occasion highlights the ambiguity of his attitude to Kemal

throughout the war. In 1913-14 he had been at great pains to remove politics from

the Army and to mould it into an instrument obedient to his purposes, and he could

be quite ruthless about discipline. Yet he usually behaved most tolerantly towards

Kemal, though aware of his great ambition and the need to watch him carefully. In

March 1916, on being pressed to promote Kemal, he remarked: 'I have just signed his

promotion. .. .But you don't know Mustafa Kemal as well as I do. True he is very

valuable, but he is also very greedy. Make him a brigadier and he'll want to be a

general. Give him that, and he'll want to become C-in-C. If we agree to that too, he

still won't be satisfied . . .There is no limit to his ambition. Therefore we have

to handle him very skilfully and give it to him little by little to keep him happy.'

Years later, on hearing of Enver's remark, Kemal commented: 'I hadn't realized Enver

had so much insight. He was entirely right.'[21]

Even before 1918 Kemal's high-handed acts had certainly given Enver every excuse to

act against him, and his later political intriguing with Fethi (and perhaps Cemal

Pasha) to overthrow Enver had even reached British ears. A printed memorandum of 27

May 1918 by the Political Intelligence Department at the British Foreign Office

stated: 'There is considerable evidence that the discontent among the officers is

serious, and . . . that the aim of the movement was a separate peace. . . The

malcontents have a possible leader in a certain Colonel Kemal Bey . . . There is

reported to be resentment in the Army at the way he has been treated, and he is

rumoured to have a considerable following.'[22]

Yet Enver confined himself merely to warning Kemal when he engaged in particularly

obvious attempts against him. The reason was that Enver considered Kemal the only

man capable of replacing himself. When the CUP Cabinet resigned in October 1918, he

advised Talat Pasha to recommend Kemal to the Sultan as the War Minister in the new

Cabinet.[23]

IT IS POSSIBLE THAT ENVER'S decision to send Kemal out of the country with the Crown

Prince on his visit to Germany on 15 December 1917-5 January 1918 (to return

Wilhelm's visit to Turkey earlier in 1917) was made in response to Kemal's

intriguing. If so, it was a poor decision, for Kemal seized upon this as another

opportunity to work against the Government. He was rapidly becoming more adroit at

intrigue, and henceforward there were fewer dramatic resignations and less of the

old loud talk in drinking establishments. The aim was the same—to get himself into

a position from which he could rescue Turkey from the fatal illusions of Enver and

his comrades—but the methods were becoming more sophisticated. Nevertheless, the

great hopes he conceived at this time of being able to wield influence on the

Sultan-to-be were never realized.

Vahideddin was almost pathologically shy, and the extraordinary mannerisms he

affected to conceal this when confronted with strangers made Kemal wonder after

their first meeting, a few days before they left for Germany. As he left the Crown

Prince's villa he remarked to Colonel Naci [Eldeniz], a former instructor of his at

the Military Academy, now a corps commander, who was to accompany them as

interpreter: 'That wretched pitiful man. ... Tomorrow he will be Sultan; what can we

expect from him?' Naci had answered 'Nothing'. But the possibility also occurred to

him that Vahideddin pretended to be ineffectual for self-protection. To a friend he

remarked: 'Either he is a very clever man or a total imbecile, I don't know which.'

|

| |

|

|

Vahideddin

(a.k.a., Mehmet IV,

Vahdettin) |

When Kemal and the Crown Prince met again on the train taking them

to Germany, he thought he had his answer. He found Vahideddin a different man—still

withdrawn and nervous, given to long silences, but able at least to carry on a

conversation now that he was in a less formal situation. He knew little of the world

beyond Palace circles, and almost everything he knew gave him cause to be fearful for his

future, but Kemal's hope grew. He explained the change to himself: 'The Heir Apparent, who

the first time we had met in Istanbul had behaved so strangely under the influence uf

conditions easily understood by those who know that period, saw no harm in showing his

personality as it really was after leaving Istanbul and seeing himself really free,

especially after he realized that his hearers were trustworthy men.' Every day for the

next three weeks he worked on him carefully, enlisting the aid of Naci and some other

trusted members of the entourage, attempting gradually to instruct Vahideddin in their

view of the Empire's situation and needs.

It was one of the few times that the man who would soon be Sultan had completely escaped

the stifling influence of the Palace; the first time probably in all his 57 years that he

had extended conversations on matters of gravity with men important in the world outside

the Palace, and been taken seriously by them as a man with a responsibility for making

decisions. He expanded visibly under the effect of this. He revealed to Kemal his disgust

with Talat and Enver and his conviction that they were doing the country harm, encouraging

the General to talk even more freely. Kemal did all in his power to enlighten the Prince

on the state of the Empire, the exhaustion of its people, and above all on the

impossibility of the war's ending in victory for the Central Powers, a fact he became

unshakably convinced of after his interviews with Hindenburg and Ludendorff, and

especially after their visit to the Western Front. Vahideddin, though still not very

forthcoming, gave every sign that he agreed with Kemal's views, and raised his hopes even

higher by asking Naci to become his aide. Naci was not at all pleased with the idea of

serving at the Palace, but Kemal persuaded him to accept with the argument that 'There

must be someone at his side who will explain the realities to him'.

Finally, on the last day before they were to return to Turkey, when the two of them were

left alone in the Crown Prince's Berlin hotel room after a press conference, Vahideddin

committed himself. He turned to Kemal and asked: 'What must I do ?'

'We know Ottoman history,' Kemal replied. 'There are some [precedents] that make you

afraid and suspicious. You are right to be so. I am going to propose something to you, and

if you accept I will link my life to yours. May I ?'

'Speak.'

'You are not yet Sultan, but you have seen how in Germany the Emperor, the Crown Prince

and the other Princes all have jobs to do. Why do you stand aside from public affairs ?'

'What am I to do ?'

'As soon as you get back to Istanbul ask for command of an army, and I will be your chief

of staff.'

'The command of what army ?'

'The Fifth.' It was the army which defended the Straits and hence commanded Istanbul.

'They will not give me this command.'

'Ask for it anyway.'

Vahideddin replied: 'I will think about it when we get back to Istanbul.'

It was not the reply Kemal had hoped for. Once back in Istanbul and exposed again to the

old influences and fears, the hesitant Vahideddin would be much more difficult to move to

action, but he had, he reckoned, accomplished at least something. He was now the confidant

of the man who would soon be Sultan.

Kemal had no early opportunity to test the strength of his influence over the Crown

Prince, as he fell seriously ill in the train on the way back to Turkey. For the next six

months, as the Empire moved steadily towards military collapse, he was much of the time

unable to rise from his bed, undergoing treatment first in Istanbul and then in Vienna.

While he was there in June Enver offered him the command of the 9th Army, then forming in

eastern Anatolia in accordance with Enver's ambition to occupy the Caucasus and north-west

Iran and to retake Iraq, but Kemal refused it.[24] He

was in Karlsbad, still not fully recovered, when he heard on 5 July 1918 of the death of

the Sultan and of Vahideddin's accession to the throne. Greatly annoyed at being absent

from Istanbul at such a time, but still too ill to travel, he contented himself with

sending a telegram of congratulations to the new Sultan Mehmed Vahideddin VI which was

duly acknowledged. Shortly afterwards he heard that General Ahmed Izzet Pasha had been

confirmed as the Sultan's chief military aide.

Probably not much had resulted from Kemal and Izzet's joint service on the Caucasus front

in 1916-17 beyond a mutual appreciation of the other's potential value as an ally against

the dominance of Enver; the characters of the two men were diametrically opposed, and

Izzet did not share many of the ideas of the younger generation of state officers to which

Kemal belonged. Nevertheless the latter was pleased at the news; he was certain that Izzet

would convert his largely honorary post into one of active military adviser, chief of

staff almost, to the Sultan, and he had great hopes that the latter could be persuaded to

move against Enver. In a letter of 19 July to the new Chief Chamberlain Lutfi Simavi Bey

he remarked: 'The Sultan's ascent to the throne has given birth to extraordinary hopes in

me from the point of view of the prosperity and safety of our fatherland. . .I am

completely convinced that the fatherland, the nation and the Army will be rescued from

being a plaything of Enver's.' [25] A few days later

Kemal received a telegram from his own aide in Istanbul, Cevat Abbas, advising him to

return there. Kemal replied that he was not yet recovered, but Cevat Abbas immediately

sent him a second telegram begging him to come quickly, and on 27 July he left Karlsbad,

arriving in Istanbul on 2 August.

|

|

|

|

Cevat

Abbas |

There Cevat Abbas told him that it had been

Izzet who had urgently requested his return. Informed of his arrival, Izzet came at

once to see him in his hotel room. He explained that his summons had not been

connected to any specific event, but hoped that Kemal's intimacy with the new Sultan

would be useful in diverting him into a new course of action. He felt no necessity

to spell out that this course would be against Enver and in favour of a separate

peace. Kemal agreed at once and requested an audience with Vahideddin through his

personal aide, Naci Bey. It was granted on 5 August.

Kemal's whole concern now was that he should be able to continue his former close

and frank relationship, brief though it had been, with the new Sultan. Vahideddin

greeted him warmly and Kemal, taking courage from this, asked if he might speak

freely as before. 'Certainly,' replied the Sultan, and Kemal went straight to the

heart of the matter. Vahideddin must at once take supreme command of the armed

forces; there must be no Deputy Commander-in-Chief exercising actual command (Enver

was Deputy C-in-C); rather Vahideddin should appoint a Chief of Staff directly under

himself (Kemal, of course). Before anything else he must control the Army; only

after that would it be possible to put into effect such decisions as he might reach.

Ominously, Vahideddin's behaviour reverted suddenly to that which had so alarmed

Kemal at their first meeting. He closed his eyes, and after an interval asked: 'Are

there other military leaders who think like you?' 'There are,' replied Kemal. 'Let

us think about it,' said Vahideddin, and the audience was over.

On 8 August the Sultan issued an irade changing the title of the C-in-C of the

Ottoman forces from Deputy C-in-C to Chief of the General Staff, but the occupant of

the office was Enver as before. There can be little doubt that Vahideddin was now

under strong pressure from the CUP, which was aware of his antipathy towards it. On

the 9th Kemal was invited to the Palace again, but this time the Sultan did not

allow him to divert the conversation from general points to the subject uppermost in

his mind. He hinted that nothing could be done before the near-famine prevailing in

Istanbul had been remedied. It was true that the people of Istanbul, who were

suffering from hunger and privation more severely than those of almost any other

part of the Empire, represented a potential danger to any government, but there was

no reasonable prospect of their suffering being alleviated while power remained with

the CUP and the war went on. With the desperation of a man whose hope is slipping

away, Kemal spoke bluntly: 'The first action of the new Sultan must be to take

control. As long as the power—the power to protect the State, the people and all

their interests—is in the hands of others, you will be Sultan in name only.'

Vahideddin replied: 'I have discussed what needs to be done with their Excellencies

Talat and Enver Pashas', and the interview was over. Kemal had lost. He returned to

his hotel room in despair. He noted later: 'The man we had thought to be a hadji had

produced a crucifur from under his cloak. It was necessary to look elsewhere, and

not to alarm anyone prematurely.' [26]

Though Kemal was not to be completely persuaded for fully another six months that

the Sultan could be no help under any circumstances, in truth he had never had any

chance at all. It is almost certainly not true, as has sometimes been alleged, that

Vahideddin had been paralysed with fright by the overweening ambition of the young

general who had lectured him so constantly during his German trip. Though their

long-term aims were entirely different, as he must have guessed, he had recognized

Kemal as a potentially valuable though dangerous ally against the men whom he saw at

the time as even more dangerous, the leaders of the CUP, who in his view were the

enemies alike of the Sultanate and religion. But at no time had he had the nerve to

commit himself fully to Kemal—and in fact would have been foolish to do so, as an

attempt to overthrow Enver's power any time before autumn 1918 would probably have

ended in failure. Once back in his old environment, without Kemal to support him,

his timid resolve had crumbled before the overwhelming fact of CUP power in

Istanbul. Perhaps under the influence of Izzet Pasha and Kemal's man Naci Bey he

toyed briefly with the idea of moving against the CUP on his accession to the

throne, or perhaps Izzet's summons to Kemal was an attempt to revive such an idea in

him, but it is inconceivable that he could ever have brought himself to the sticking

point. Confronted by Kemal with the prospect of really taking the gamble, he

retreated hastily into his shell.

Enver of course did not remain unaware of what was going on at the Palace. His

position in the Cabinet was by now extremely shaky; Talat had in fact definitely

decided to drop him and seek peace, and was only awaiting his moment, though Enver

did not know that.[27] In his desperation he

apparently tried to arrange Kemal's assassination. When Kemal, who had taken to

carrying two pistols, disarmed the would-be assassin, a Sergeant Idris, Enver fell

back on a less drastic but almost as effective solution. He arranged the appointment

of Kemal away from Istanbul where he could not get at Vahideddin. He was a capable

commander, and the 7th Army in Palestine needed one as a British offensive was

imminent there. The problem was to get Kemal to accept.

|

| |

Enver solved this problem neatly by disregarding protocol. Instead of offering Kemal the

post himself, he had the Sultan do so personally at an audience where German generals were

also present. The surprise was sprung on Kemal on 16 August 1918, and he had to accept the

appointment as he could not refuse the Sultan's direct order before foreign witnesses.

Emerging from the audience chamber, he met a smiling Enver. In response to Kemal's tightly

controlled but angry protest, Enver laughed out loud. It was the last time they saw each

other.[28]

KEMAL WAS CERTAINLY IN CONTACT with Fethi during his time in Istanbul in the summer of

1918, but there is no record of what passed between them. Rauf was among those who saw

Kemal off to Palestine; just before the train left Kemal drew him aside and asked him to

stay in touch with Fethi and follow events closely. Rauf replied almost stiffly: 'I have

made a definite decision not to mix in political affairs so long as I am performing

military duties, and I repeat: though I have known Fethi Bey since the [1918] Revolution,

I find it wrong to become involved in his political dealings.' [29] There is not much doubt that what Kemal was expecting at this time,

and what may have been decided already between him and Fethi, was that the latter would

soon make his move against Talat's Cabinet. If it succeeded Kemal would become War

Minister, perhaps even Prime Minister.[30]

|

|

Liman von

Sanders |

Kemal reached Aleppo on 26 August after an exhausting journey on the

collapsing Turkish railway system and left for the Palestine front the next day to take

over command of the 7th Army. His two corps commanders were his old comrades and

collaborators Ismet and A!i Fuad; commanding the 22nd Army Corps to the west was another

former associate, Refet. The situation was far worse than it had been when he had resigned

the previous year; in the interval Jerusalem had fallen, and only the stubborn resistance

of Ali Fuad had prevented the rot from spreading farther north. None of the three

so-called armies on the front could muster the strength of a well found division, and the

troops were in the last extremity of deprivation and despair. Though the army group

commander was the competent Liman von Sanders, British superiority on the front was about

two to one, even leaving aside questions of fitness, morale and supplies, and there was no

reasonable prospect of being able to stop the impending British attack. Allenby struck on

19 September, less than a month after Kemal's arrival, and immediately broke through the